History Detectives Helps Solve Wesleyan Book Mystery

|

| Valerie Gillispie, assistant university archivist, holds a rare book, which was featured on PBS’s History Detectives in July. The book is stamped with the name and address of a 19th century female anarchist and possibly belonged to a deceased Wesleyan alumnus. |

| Posted 08/07/07 |

| In June 2006, a book was discovered in the Wesleyan stacks related to the Chicago Haymarket Tragedy marked with an unusual stamp on the cover.

1887-published artifact to Special Collections and Archives, where the book encountered a deep investigation. How, then, did one of her books end up in the Wesleyan stacks, asked Valerie Gillispie, assistant university archivist, who received the book. Did this book actually belong to Lucy Parsons? Is the stamp authentic? Is the book rare? Gillispie called the producers at PBSs History Detectives, who agreed to investigate. In January 2007, a crew came to Wesleyan to see the book and film. For 12 hours, History Detectives filmed scenes on the front steps of Olin Library, the Smith Reading Room and College Row. The show aired on July 16 with surprising findings. Although the late 19th century book was declared authentic, based on the age of the paper and typography, the stamp did not prove it ever belonged to Lucy Parsons. It turns out, Lucy was selling several copies of Spies book to raise money, and she probably stamped her name and address on the books so people who bought the books would know where to go for more anarchist materials, Gillispie says. So, the book probably didnt belong to Parsons, but it still was a big part of that historical movement. Nevertheless, the book and stamp are both rare finds. An antique book dealer interviewed on the show said hes never seen a Lucy Parsons stamp before, and for good reason. In the 1920s, the attorney general raided hundreds of 5radical headquarters and destroyed anarchist-related reading materials. Somehow, this Parsons-stamped copy survived and ended up on Wesleyans shelves. In a world-wide catalog search, Gillispie says she can only locate 30 copies of the Spies autobiography. And based on the History Detectives show, she believes Wesleyan owns the only copy with the Parsons stamp inked on the cover. All evidence of Lucy Parsons existence was discarded, so it is amazing that this book with her name and address survived. Its probably passed through many, many hands and that alone makes it a very significant piece, she says. But how did the book end up at Wesleyan? Thats one answer History Detectives was unable to find. Olin Library records show Spies book was added to the stacks collection in the early 1970s, and it was checked out six times in the past 10 years. Gillispie suspects the book might have belonged to Harry Laidler, class of 1907. Laidler, who wrote many books about the labor movement and socialism, died in 1970, and left his personal library of 800 books to Wesleyan. Many of these books and pamphlets were related to labor movements. It would make sense, based on the time the book was catalogued, that Laidler owned this book. Its just a hunch, but its the best guess we have, she says. The book will be recatalogued and stored at Special Collections and Archives rare book collection. The book cannot be checked out, but it is available to the public for viewing. |

| By Olivia Drake, The Wesleyan Connection editor |

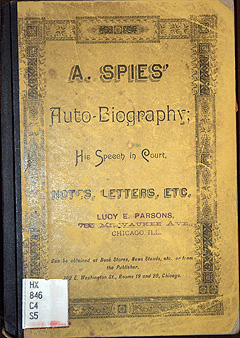

The book, written by August Spies, was titled Auto-Biography, and appeared to be stamped with the name and address of Lucy Parsons, a 19th century bi-racial anarchist who promoted better labor conditions. Parsons husband was among those convicted and executed in 1887 for bombing police during the Haymarket riot; police kept her under surveillance for the rest of her life. Parsons died in 1942 from smoke inhalation, and about 1,500 of her books and papers were confiscated by police and disappeared.

The book, written by August Spies, was titled Auto-Biography, and appeared to be stamped with the name and address of Lucy Parsons, a 19th century bi-racial anarchist who promoted better labor conditions. Parsons husband was among those convicted and executed in 1887 for bombing police during the Haymarket riot; police kept her under surveillance for the rest of her life. Parsons died in 1942 from smoke inhalation, and about 1,500 of her books and papers were confiscated by police and disappeared.