5 Questions With … Barbara Juhasz

Q. How did you first become interested in psychology?

A. I’ve always been fascinated by how the mind works and why people behave the way they do. Since early in high school, I had the idea that I wanted to be a research psychologist. At that time, I really did not know what the field of psychology actually consisted of. Like most people, I believe, I thought psychology meant psychopathology. Once I started studying psychology at the college level, I realized that the field of cognitive psychology was what really interested me.

Q. What drove you to explore reading and eye tracking?

A. When I took a statistics class at Binghamton University, I had the opportunity to participate in a Master’s thesis project examining eye movements and reading. It was being conducted in the laboratory of Albrecht Inhoff. I had always been interested in literature and languages and was excited that my love of both psychology and reading could be combined. I was also fascinated by the eye-tracker. It is still amazing to me that by recording where a person looks on a computer screen, we can infer so much about what it happening in their mind. It is an accurate, non-invasive way to examine cognitive processing.

Q. What consistent results from eye tracking studies tell us the most about how people read?

A. Readers alternate between brief pauses, called fixations, and rapid eye movements, called saccades. Fixations last between 200-250 milliseconds (on average) and these are where information is gathered during reading. Our visual system shuts down during saccades, so although we have the impression that our eyes glide smoothly across the page, reading is more like a slide-show.

Fixation durations are very sensitive to the difficulty of the reading material. We look longer at harder words and phrases. There are also individual differences – children learning to read have longer fixations than adults and individuals with reading disabilities have longer fixations as well.

We also gain information to the right of where we are currently fixating in English. Our perceptual span, where we can obtain information during a single fixation, extends roughly 15 letter spaces to the right of fixation and three to four letter spaces to the left. This span is reversed in languages such as Hebrew, which are read right-to-left (See Rayner, 1998).

Q. How have eye-tracking machines and their software evolved in the past 10 years?

A. Eye-tracking machines used to be terribly complex. The first eye-tracker I learned how to use took at least one month to learn and had tons of knobs and mechanical parts which broke quite frequently—usually when you needed data for a conference or some other important event! Luckily, there are now several companies which make much more user-friendly eye-tracking equipment. I can now train an undergraduate research assistant to use the eye-tracker in less than a day.

Probably because of this, there are many more researchers conducting eye movement studies today. Eye movement researchers have their own conference – the European Conference on Eye Movements, which has grown in attendees over that past 10 years. One important aspect of choosing an eye-tracker is how precise you need it to be. For my research, I need an eye-tracker which is very precise spatially and temporally. I therefore use an EyeLink 1000 (SR Research. Ltd.). This eye-tracker records eye position every millisecond and allows me to see what letter a person is looking at as they read.

Most companies also sell dedicated eye-tracking software which can create and analyze experiments. In addition, many labs create their own software. I often use software that was developed at my graduate university, University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

The trick with conducting eye movement research is not in learning the equipment, but in learning how to design a good experiment and how to interpret your results. It is advisable to spend some time in an eye-tracking laboratory before running your first study. Eye-tracking experiments can take a long time to run, and you do not want to be left with data which is not interpretable at the end. When I was lab manager at the eye-tracking lab at UMass, we had visitors from all over the world come to learn how to conduct eye movement studies.

Q. What is the interesting link between Wesleyan and eye-tracking that you’d like to share?

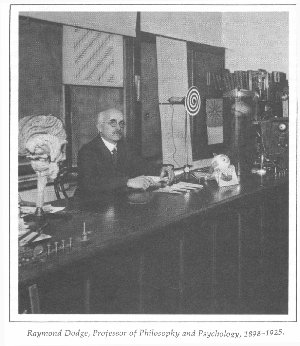

A. When I arrived at Wesleyan, I explored the psychology department’s history. I discovered that Raymond Dodge helped to run the first psychology laboratory at Wesleyan in 1898, when it was housed in the Philosophy Department. This was exciting to me as an eye movement researcher, as Raymond Dodge is considered to be a pioneer of eye movement recording. He developed his own eye-tracking devices to record eye movements during reading and during rotational movements. Thus, much of the early work examining eye movements experimentally was actually conducted at Wesleyan.