Scott ’76 Reflects: On Being Black and Female in Late 1970s TV Journalism

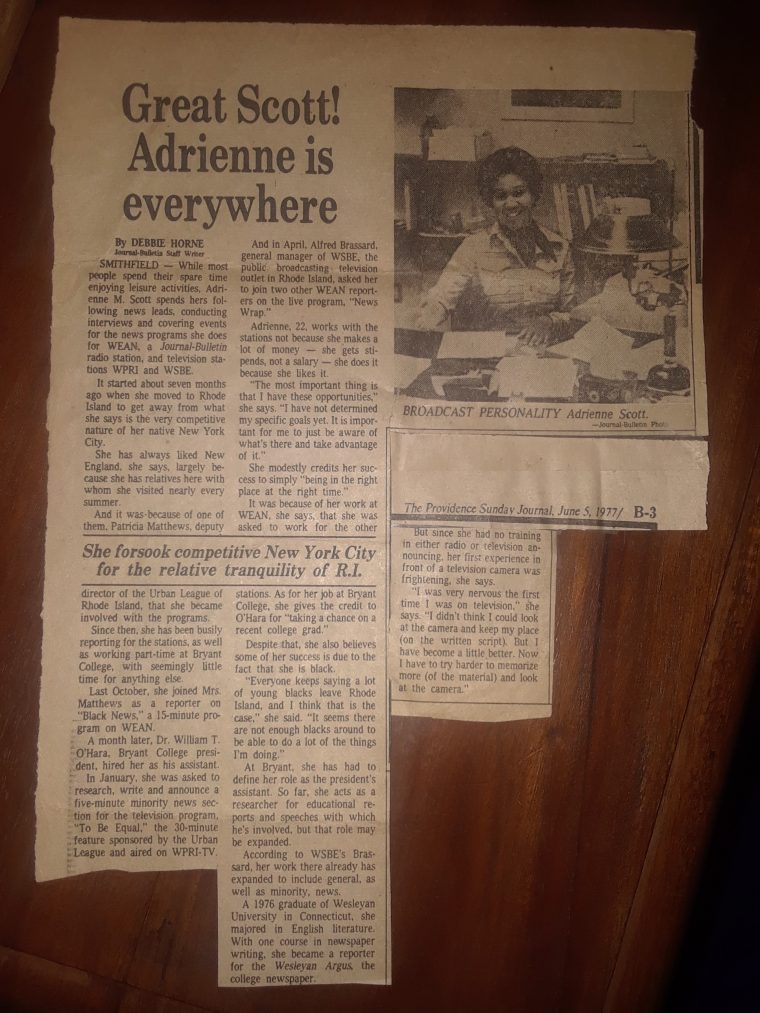

The Wesleyan magazine issue on the future of journalism (2018, issue 2) prompted Adrienne Scott ’76 to write a letter to the editor, recalling a high point in her early career in journalism: when legendary boxing champion Muhammad Ali granted her an exclusive interview. Scott, who had been a columnist for The Wesleyan Argus as an undergraduate, as well as a student of University Editor Jack Paton ’49, P’75, was at that time a young journalist and the first African American full-time news reporter at WPRI-TV in Providence, R.I.

The Connection reached out to Scott to continue the conversation that began with her letter, asking for her perspective on journalism in the late 1970s.

Q: When did you first become interested in journalism?

A: In the late ’60s and early ’70s, before I left the Bronx High School of Science, I remember thinking that the public affairs reporters and interviewers with panel shows were fascinating. I even called in to radio shows with comments; I was interested in the world and there were some pretty big issues to discuss.

Q: How did you come to start your journalism career in Providence?

A: My aunt in East Providence offered to have me live with her while I picked up some stronger typing skills before heading back to New York City for a job in publishing.

Another aunt was deputy director of the Rhode Island Urban League, so I assisted her in writing and broadcasting Black News, a 15-minute public service radio show. Then I was offered a half-hour show through the Urban League connection on WPRI-TV, the ABC affiliate.

A few months later, I was startled when the general manager of WPRI-TV asked if I’d become a news reporter.

Q: What was that like?

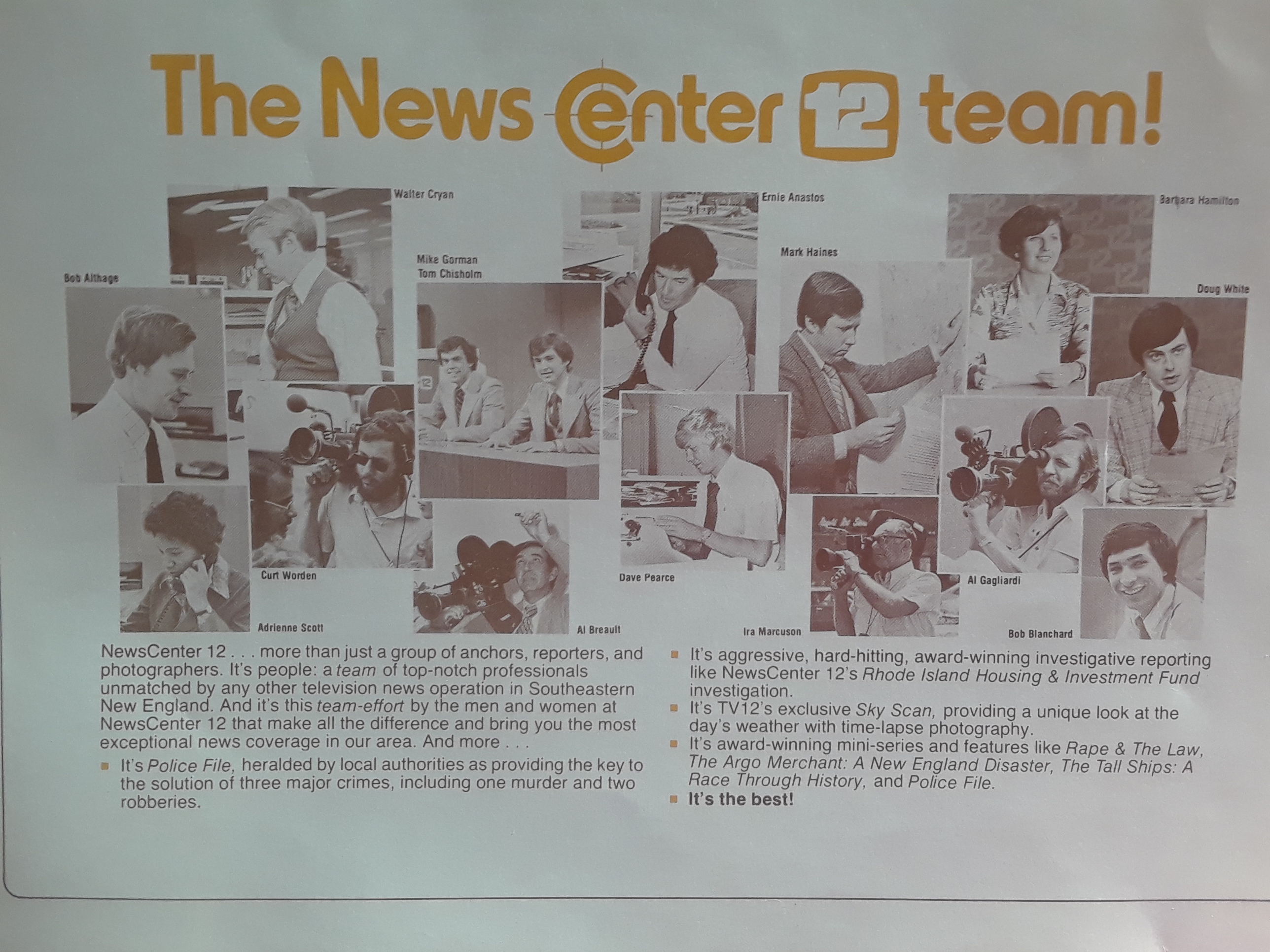

A: It was tough. I was the first full-time news reporter who was African American. And there was only one other female reporter out of the 25 people in the newsroom.

The general manager wanted diversity, both racial and by gender—and it was time—so he’d made a deal with the Rhode Island Urban League to hire me, but, apparently, he hadn’t broken the news to the head of his newsroom: On my first day ever of work as a news reporter, my news director personally assigned me to the top story of the night, a shooting. The news staff were speechless; he clearly was testing me. A year later he apologized to me at a Christmas party. “I shouldn’t have done that to you. You turned out to be a good reporter and I’m sorry.”

Another tough part was that one of the photographers was socially maladjusted, and I was assigned to work with him, just like everyone else. I had to sit next to him in the news cruiser, traveling to stories, while he repeatedly called me a “n****r” and a “whore.”

At the time I thought, “This is just what you have to deal with,” so I didn’t say anything. Eventually, I did ask the news director if I could occasionally be assigned to a different photographer. He said no. Categorically no.

I do calibrate how much change has occurred since those days.

Q: Please tell us how the Muhammad Ali interview came to be.

A: I was assigned to cover the press conference, and it was like a circus, with all the people who adored him crowding around him in the Biltmore Hotel after the fight.

He spotted me and my photographer in the crowd. He had his assistant come over and tell me, “We can finish the interview here, with the other reporters, and you can come up to my suite with your cameraman and your still photographer and we can do some more talking there.”

This was unbelievable, really. I know how green I was, and I wasn’t a sports reporter. He was known to have a commitment to help the black community anywhere he went.

Q: But you didn’t stay in journalism?

A: I had asked to be considered for coanchor of the noon news, a position in which the senior anchor, the late Walter Cryan, said I was quite good whenever I filled in. My news director ignored this fact and said the news market wasn’t ready, and he wouldn’t even give me a trial period. I looked around for someone to advise me—how to appeal that decision, put pressure, file a lawsuit. There was nobody. We didn’t have an Association of Black Journalists in our area. I was blocked from going forward by a bigoted man.

Q: What did you learn from your work in journalism in that era?

A: Young people, in general, need mentors—and young people of color and women, especially, need mentors when they are breaking into new fields. They need to speak up and not let anyone deter them from their dreams.

I went to graduate school at Boston College, then into higher education administration. After a career in that, as well as in teaching, I’m now a part-time tutor. I invite anyone to contact me about their career path. This has been a part of processing my anger and redefining my purpose.