Medieval Art History Class Researches, Creates Lights of Late Antiquity Exhibit

Between the first and fourth century CE, ancient Egyptians believed frogs symbolized fertility, rebirth, and the renewal of life. After a hibernation period, frogs would come “back to life” near the rising Nile River, which provided water and nutrients to the barren landscape in early spring.

During this period, the frog not only became a metaphor for a renaissance, but it also became a popular icon. It could be seen in Egyptian artwork and sculptures, it manifested in the frog-headed goddess Heqet, and it could even be found on everyday oil lamps. These kidney-shaped “frog lamps,” as they later became coined, were crafted from clay molds. While some are impressed with palm fronds, others include visible frog legs in their designs.

The “frog lamp” is among almost two dozen ancient and medieval objects presented in a new exhibition in Olin Library. Drawn from Wesleyan’s Archaeology & Anthropology Collections, and accompanied by a virtual exhibition, “Coinage and Clay: Lights of Late Antiquity” displays a variety of oil lamps alongside a selection of coinage from the Roman, Byzantine, and Sasanian empires, and more.

Research for the exhibit was conducted by 20 students from the Art History 213 course: Cross, Book, Bone: Early Medieval Art, (ca. 300-1100), taught by Joseph Ackley, assistant professor of art history. Each student was responsible for one of the exhibition objects, and they researched and wrote object labels for both the in-person display and the online component.

“The exhibition mixes humble, mundane clay lamps with wealth embodied in the form of gold, silver, and bronze coinage,” Ackley explained. “In addition to blending high and low, the exhibition showcases two very different types of historical artifact, each of which raises different sets of questions and affords a different lens onto the past. Given that lamps generate light and coins, when freshly polished and untarnished, dazzlingly reflect light, ‘light’ emerged as connective tissue for the exhibition title.”

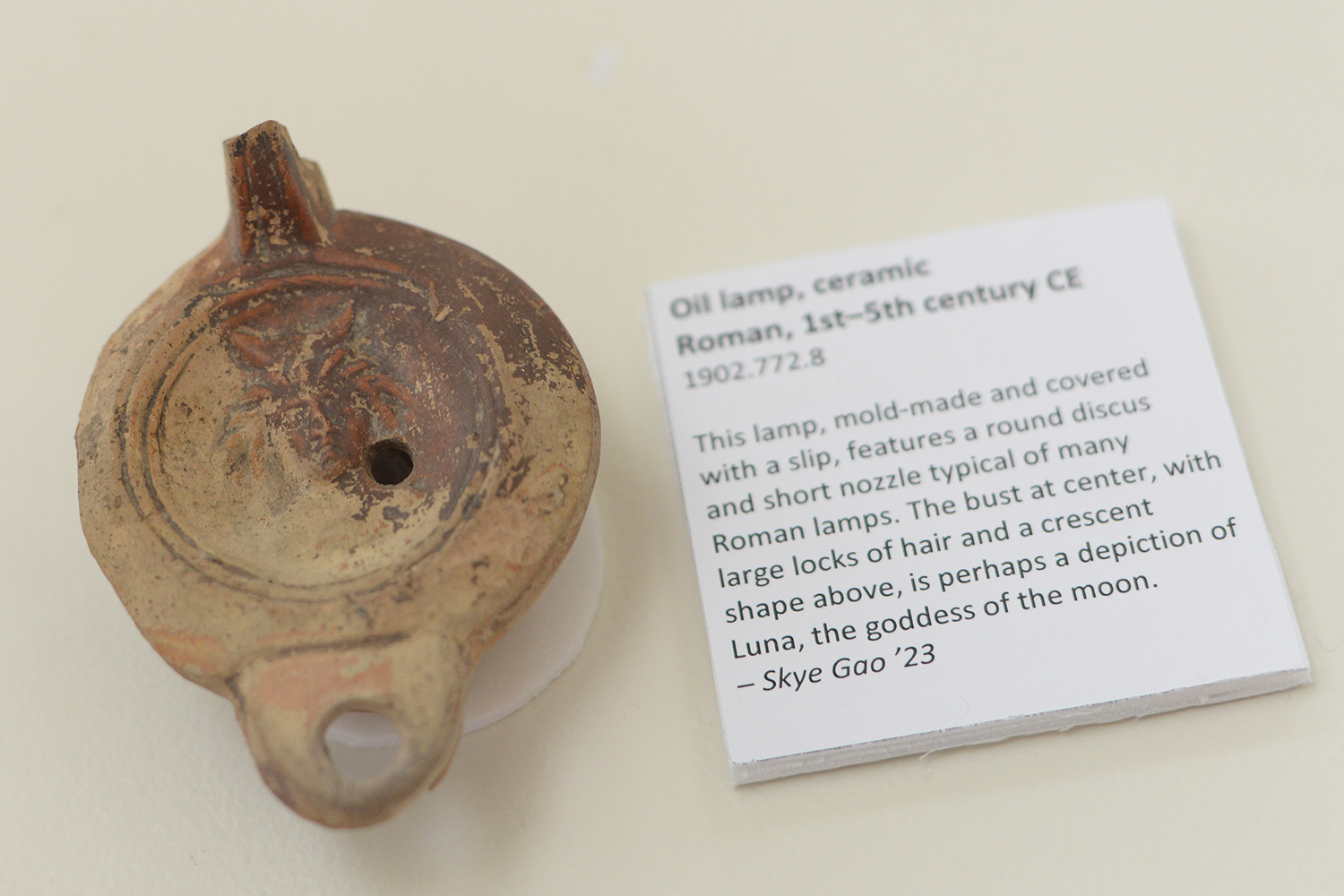

In addition to frog lamps, the exhibit showcases several other eloquently-crafted lamps, which are prime examples of Late Antique and Byzantine art. One Roman oil lamp is decorated with a bust of a figure with large locks of hair and crowned with a crescent. This likely is a depiction of Luna/Selene, goddess of the moon. Another lamp pictures a musician figure with surrounding fish and ornate square motifs. Based on its ovular base and ornamental border, it likely comes from the fourth-century Roman province of what is now Tunisia.

“There is a striking tactility and sense of immediacy to the lamps,” Ackley said. “It’s difficult to describe the experience of holding something that is 1,500 years old, an object that a pilgrim, shopkeeper, or merchant in 5th-century Tunisia or 8th-century Constantinople would also have held, and we are fortunate that we were able to provide our students with such an opportunity. The tactile immediacy of such an encounter fires the curiosity to know more.”

The coins displayed in the exhibition show a range of historical figures, from Pontius Pilate and Constantine the Great to Justinian I and King Cnut of England. They date as far back as 29 CE with the bronze prutah of Pontius Pilate, which was used in the Roman province of Judaea. The prutah is marked with a ladle-like utensil known as a simpulum, which was used by priests to taste the wine before pouring it onto a religious sacrifice. The reverse side depicts three ears of barley.

Another bronze coin, minted in Egypt in 136 CE, is struck with the bust of Antinous, the young lover of the Roman emperor Hadrian. The reverse side shows Antinous clothed in only a cloak, riding a horse. This coin, now patinated and worn, is compared on the virtual exhibition with a more legible example that depicts a bust of Antinous on one side, but with a seated Demeter on the other.

“After [Antinous’s] premature death in Egypt, he was deified on Hadrian’s order,” writes Loic Shenghan Gao ’22 in the online exhibit. “The cult of Antinous spread rapidly along with the promotion of Hellenism, and both a city and a constellation were named after him. Coins were struck with his image, elevating Antinous practically to the status of a member of the imperial family.”

When teaching art history, Ackley is constantly looking for ways to get his students in front of physical objects, which “is simply essential to the discipline and to a fuller understanding of the subject,” he said. Pre-pandemic, he brought classes on field trips to the Yale University Art Gallery and the medieval collections of The Cloisters in New York City. But Ackley also was aware that Wesleyan’s own collections boast a plethora of objects that could equally enrich a classroom discussion or project.

After the students completed a reading assignment to acquaint them with the basics of antique lamps and coins, Ackley took his class to the WUAAC collections and introduced them to Archaeology Collections Manager/Repatriation Coordinator Wendi Field Murray. Murray explained that the collections include about 30,000 objects from around the world, many of them collected during the 19th century when they were part of Wesleyan’s Orange Judd Museum of Natural History.

“Since the WUAAC is a teaching collection, [objects] are meant for students to handle, analyze, and explore,” Murray said. “Many people assume the collection is only relevant to archaeology or anthropology courses, but I am on a tireless campaign to help people think more expansively about their relevance to Wesleyan’s curriculum. Whether you want to use them to talk about materiality, colonialism, repatriation, the history of science, human-environmental relationships, art, museum ethics, chemical analysis, the party scene in ancient Greece—the possibilities are really endless!”

Ackley’s students were each assigned to research one object and tasked with writing a description for both the physical and virtual exhibition. They also needed to write a formal condition report, which is a standard museum document that must always be completed before an object goes on exhibit.

“While the research component of their project focused on historical interpretation, this assignment required students to intensively analyze the physicality of their object – where do you see signs of wear or damage? Where is the coloring different? Is any part of the design obscured? Do you observe any weak points in the object that we need to keep in mind when handling or mounting it for exhibition? We did not have any prior condition reports on file for these objects, so the students’ work was integral to improving our documentation of them, and our ability to monitor and care for the collection,” Murray said.

This academic year, the WUAAC will have hosted about 50 class engagements with the collections, representing several different departments. Rarely do classes create an exhibit from their work.

“This exhibition was a hands-on opportunity for students to work with actual historical artifacts, holding and (carefully) handling them, looking at them up close, and studying them in detail,” Ackley said. “Students were equipped to put these objects in their larger historical context while attending to the complexities and significances of these artistic traditions.”

Photos of the exhibit are below: (Photos by Olivia Drake)