New Book Chronicles History of Community Health Center

What Mark Masselli Hon ’09, P’15, ’16 had to do in 1972 to start Community Health Clinic, a local health clinic that offered free care to the underserved in Middletown was, in retrospect, almost impossible.

Renting a storefront as a 20-year-old? Opening the doors and offering medical services without a license or permit? Masselli had dropped out of Wesleyan, so there was no degree backing him up. The students in Charles Barber’s service-learning class were baffled.

“It was a seismic moment when a student commented, ‘you couldn’t do what you did now in 2021’ … too many rules, too many eyes,” said Barber, the author of a new book chronicling the health center’s unlikely rise from a storefront clinic to a model of care across the nation.

Barber recalled that Masselli, the founder, president, and CEO of Community Health Center of Middletown, pushed back hard on the student. “You can do it,” Masselli said. “Anyone can do it at any time.”

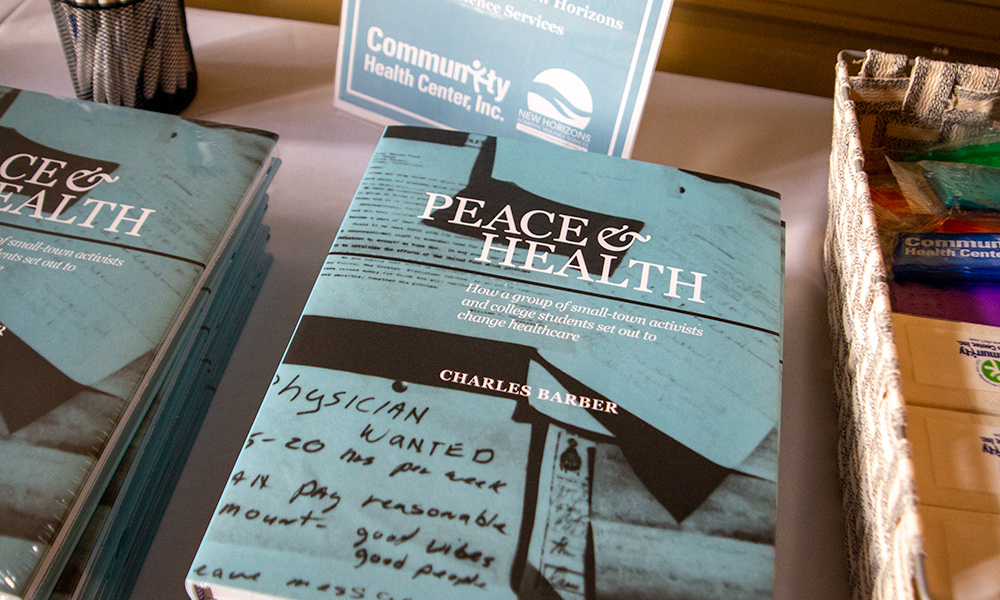

Barber, associate professor of the practice in letters, and Masselli gave a talk on Friday, November 4 at Russell House about Barber’s new book “Peace and Health.” The book was published earlier this year.

Barber began by reading a few pages about Masselli’s early efforts in the 1970s, which included sleeping outside a possible storefront location to catch a difficult to wrangle landlord. He then jumped ahead in time to Masselli’s efforts to mobilize thousands of lifesaving vaccines for a drive-thru clinic at the height of the COVID-19 crisis.

“It reads like a novel, but it’s all true,” Masselli said. “It was a crew of people who came together because of the rallying cry that health care is a right and not a privilege.”

Barber pointed out that Masselli’s ethos came directly out of the Wesleyan environment of the late 1960s and early 1970s. Students were striking against the Vietnam War. The massacre of college students at Kent State furthered distrust in the government. The Black Panther trials in New Haven put social justice in the forefront. It was a fraught, yet fertile time, and Masselli’s work was at the heart of it. “All we wanted to do was make a difference in the community,” Masselli said.

Masselli and a small cohort of Wesleyan students worked to get the clinic running, facing resistance from the local medical establishment and their own limitations as poor college students. “While we didn’t have any money, we had a quiver full of arrows available to us from Wesleyan,” said Masselli.

He accomplished this with a single-minded approach to his work, Barber said. “Mark didn’t just do what the state wanted to do. He did what was best for patients.”

Masselli believes in allowing young people the opportunity to lead and to introduce new ideas—something Wesleyan students are adept at doing. He had a message for the students in the audience, attentively listening attentive as he and Barber spoke: “We really need this generation to do what we did,” Masselli said.