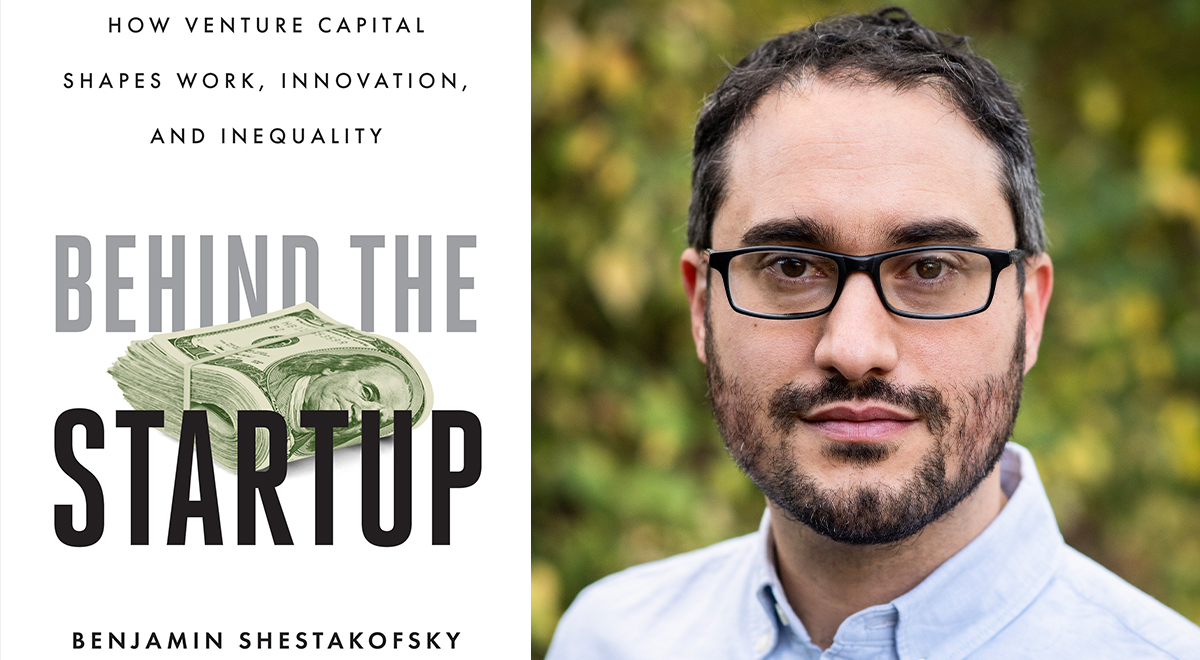

In a New Book, Alumnus Examines Venture Capital’s Impact on Startups

For decades, many people thought that technology startups were a source of positive change in the world and an economic driver for the United States, said Benjamin Shestakofsky ’05, assistant professor of sociology at the University of Pennsylvania. But over the last 10 years, public opinion of tech start-ups has swung a different way.

“People have become increasingly aware of the social problems that startups can leave in their wake as they grow,” Shestakofsky said.

Alongside the data leaks and spread of misinformation that are popular topics in federal hearings and media reports, there are other costs to technological growth and development. The growth-hungry tech industry, in some cases, has also created wealth disparities and poor working conditions for staff, Shestakofsky writes in his book, “Behind the Startup: How Venture Capital Shapes Work, Innovation, and Inequality.” He argues that there should be more focus on changing the funding structures that create the rapid-growth technologies causing societal harm rather than on re-working the technologies themselves, as has been the subject of most of the material published in this sector.

Shestakofsky interest in researching venture capital (VC) — when an investment firm provides funding to an early-stage company in hopes it will grow and provide a significant return on investment — developed after an experience working at a startup founded by a connection he made at Wesleyan, he said. Starting in 2012, he spent 19 months embedded within a tech startup — which he refers to under the pseudonym “AllDone” throughout the book — doing participant observation research to find out how venture capital investment in a firm impacts the experience of its workforce. He used his experience at AllDone as a case study of the startup universe, he said.

He found that the company’s culture was so focused on growth once it took venture capital funding that it often left behind the lower-level workers that made the company function and directed most of the financial gain to its most senior executives and investors.

“Most people might think that a startup’s mission is building new products and new technologies, but in reality, I think first and foremost, we have to think of venture-backed startups as financial assets,” Shestakofsky said. “Once a company has taken VC funding, its priority has to be increasing the value of that asset at all costs.”

The AllDone Experience

AllDone is a successful startup platform that links local service providers — house cleaners, tutors, wedding photographers — with potential buyers. Its workforce at the time of his research was made up of three main hubs: an office with engineers and product designers in San Francisco; customer service workers in Las Vegas who worked from home; and a third cohort of data-entry staff in the Philippines who also worked from home . While they all worked under the same umbrella, Shestakofsky found that the experience of staff in each office was wildly different from one another.

There were vast wealth disparities between these three offices, he said. The product-designing office workers in San Francisco were lavished with stock options and high salaries, while Las Vegas workers were making near minimum wage, and those in the Philippines were earning less than $3 per hour at the time. Staff in the Philippines and Las Vegas — which accounted for 92 percent of the company’s total workforce — were also categorized as remote, off-site contractors without benefits like health insurance or company-matched contributions to a retirement account.

“The workers behind the scenes are creating so much value and capturing so little of it,” Shestakofsky said. “We need to think more about how the vast amounts of wealth generated by new technologies can be shared by more stakeholders.”

Alongside the financial disparities, AllDone’s San Francisco staff were experimenting with the product and business model at a rapid pace to keep up with investor pressure for growth, which caused significant ripple effects for the day-to-day work of its other offices. Shestakofsky said the team changed the fee structure to increase revenue, which upped prices for users by more than five times. He said both users and the staff handling user complaints were often frustrated by the rapid changes to the platform. “It’s a recipe for putting your frontline workers through a tremendous amount of stress,” he said.

“Venture-backed experimentation can create a lot of dissatisfaction among users that technology itself can’t solve,” Shestakofsky said. “You have to put human workers in front of that mess to try and clean it up, and that’s what I saw happening at AllDone.”

A Better Future of Funding

Shestakofsky highlighted other funding models that could produce better results for workers and society writ large. He pointed to the privately-owned online bulletin board Craigslist, which intentionally charges a small sector of its customer base and sticks with its product that fulfills its mission of fostering an open internet, he said. Craigslist does not collect or sell user data to advertisers either — a goldmine often exploited by big tech’s largest players.

For the future of startups, he recommended fostering a tech ecosystem that could support more non-profit tech organizations or co-ops, where a company is owned by its workers. The home-cleaning service Up & Go is a worker co-op that shares 95 percent of its revenue with workers, who are nearly all women who immigrated to the United States from Latin America, he wrote.

“The VC model is designed to funnel the lion’s share of the rewards created by tech companies to the people at the top. There are a lot of real-world examples of other funding models that can share the benefits generated by innovation more broadly,” Shestakofsky said.