In “Double Vision” at Zilkha Gallery, New Works By Jeffrey Schiff

In 1786 the American Philosophical Society published a volume of essays and commentaries by its members on natural curiosities: a partridge with two hearts, a horse with a worm in its eye, a slave girl with mottled skin.

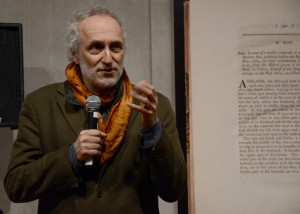

More than 220 years later, Professor of Art Jeffrey Schiff has transformed these Enlightenment-era accounts into a series of 16 artworks now on display at Wesleyan’s Ezra and Cecile Zilkha Gallery

“Double Vision: Transactions of the American Philosophical Society,” runs through Sun., Feb. 27, with a panel discussion scheduled for Feb. 22 at the gallery.

“The troubles we continue to have with notions of the ‘natural,’ the ‘aberrant’ and what constitutes evidence and rationality seem to me to be rooted in the intellectual origins unwittingly revealed in the Transactions,” Schiff says, referring to his source text, Vol. 2 of the Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. “And the current resurgence of political claims using our founding documents to validate cultural traditions remind of the malleability of such material.”

The American Philosophical Society (APS), the oldest organization of its kind in America, was founded in 1743 by Benjamin Franklin for “promoting useful knowledge” and still exists today. Early members included statesmen, lawyers, university professors, intellectual revolutionaries and distinguished foreigners, among them Thomas Jefferson, Thomas Paine, James Madison and the Marquis de Lafayette. The various editions of the Transactions included articles by the members.

Schiff had previously found inspiration in an Enlightenment text – Diderot’s Encyclopedia was the springboard for his 1998 show “L’Encyclopedie: Miriotier.” Digital prints from that show now hang in the forensic biology lab of New York City’s Office of Chief Medical Examiner.

About eight years ago, Schiff approached University Archivist Suzy Taraba looking for new sources from the same time period: “‘What else have you got?’”

Among Olin Library’s Special Collections was an original edition of Vol. 2 of the Transactions, acquired by Wesleyan in 1918. Schiff – a Guggenheim Fellowship winner and the mastermind of the the celebrated public art installation of 2003 called “The Library Project” – was riveted.

“These guys are well educated, sharp observers of whatever’s around them,” he says of the APS’s members in a recent WNPR interview. “They had a sense that they could take on anything.”

Elaborating later, he says, “I am primarily interested in this moment when rationality and scientific method first gain traction, yet are encumbered and influenced by inherited ideologies and social and political structures. I am interested in the enduring influence that such structures still hold over our own imaginations.”

From Schiff’s imagination sprang five groups of artworks based on three accounts in the volume – “Account of a Worm in a Horse’s Eye,” “Two Hearts Found in One Partridge” and “Some Account of a Motley Coloured, or Pye Negro Girl and Mulatto Boy.”

Each group of artworks refers to one or more of the articles, large-scale photographs of which are part of the show, which was curated by Andrea Hill of Seven Hills Advisory.

Because of the close relationship between the texts and the art, Schiff encourages visitors to read the accounts, then to consider his work. “It’s really important to read those to understand what’s going on here,” he says.

In “Propositions” he presents an array of sculptures made of laboratory tables bearing interconnected glass flasks filled with isolated deposits of oil and water that threaten to comingle. In the view art critic Nancy Princenthal, author of the show’s 36-page illustrated catalog, the “Propositions” represent “the kinds of contamination that resulted, 18th-Century naturalists speculated, in mottled skin and worm-infested eyes.”

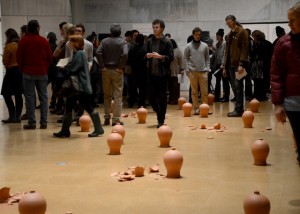

In “Terra(Cotta) Incognito” the viewer faces a field of terracotta pots, some smashed to reveal their contents, conveying, in Princenthal’s words, that “revelation comes as the price of destruction.”

“Mappa Mundi,” a soaring scaffold of 37 digital prints, refigures the body of a slave with mottled skin as an abstracted nautical map. In effect, Princenthal writes, “Schiff thereby brings together two sets of measurements for unstable entities, the fluid categories of race, the menacingly changeable seas.”

And, in a series of individually titled wall-mounted sculptures, a stereoscope joins separate images of animal hearts – a tortoise’s with a man’s, for instance – into one unstable image. The last stereoscope in the series fuses images from two iPods playing different views of the Philadelphia street where the horse with the worm in its eye was encountered – one representing the horse’s view, the other the worm’s.

“Schiff has created a series of works that explore vision and this corruption by culturally shaped preconceptions,” Princenthal says, “while also celebrating the spirit of scientific and humanistic inquiry for which the Enlightenment was distinguished.”

“Double Vision” opened with a well-attended gallery talk on Jan. 25.