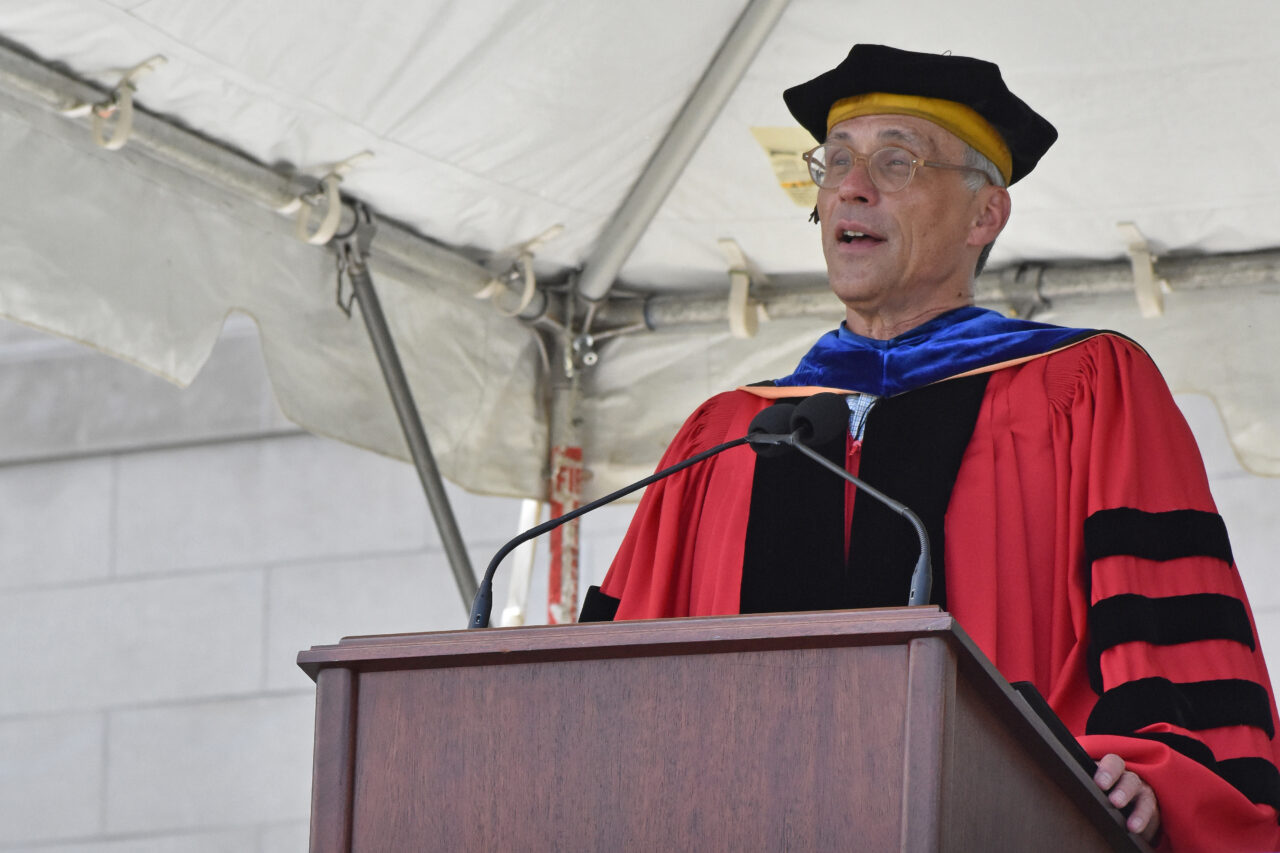

President Roth ’78 Urges Class of 2022 to Combat Culture Wars with “Culture Peace”

President Michael S. Roth ’78 urged the Class of 2022 in his Commencement Address to combat the nation’s culture wars with “culture peace” of the sort cultivated through a Wesleyan University education.

“I believe to be true to our academic and civic purposes, Wesleyan’s mission reminds us that we must become practical idealists, making peace where we can by promoting open inquiry and free expression. We must defend those who want to participate in this endeavor from threats of violence or marginalization while cultivating respect for intellectual diversity. By practicing culture peace, we will be more open to discovery, including the discovery that it’s time to change our minds and listen more carefully to others. Practicing culture peace at a time of culture war is not easy; but in the long run, it’s the antidote we need to today’s cultivation of outrage and conflict,” Roth told the graduates.

Roth made the following remarks during Wesleyan’s 190th Commencement Ceremony on May 22:

Members of the board, members of the faculty and staff, distinguished guests, and new degree recipients, I am honored to present some brief remarks on the occasion of this commencement.

Americans agree on little these days, but they agree on this: the country is embroiled in a culture war. Scapegoating is back in style. Populist elected officials find it expedient to attack vulnerable groups—from gay kids in schools and libraries, to trans people wherever they try to build lives of meaning and purpose. Culture war is an apt name for this kind of prejudice and cruelty, and I hope your Wesleyan education has given you tools to stand against these shameful attacks.

But not every debate is a fight; not all differences require combat or cancellation. Sure, it works on social media to portray oneself as part of a group of warriors defending a way of life or a culture by pointing to or sometimes just inventing an enemy that can arouse fear and distaste. Those people are not just different from us; they are a threat to our way of life. I also hope your Wesleyan education has given you the tools to be aware and beware of self-righteousness and moral self-satisfaction—from whatever side of the political spectrum from which it stems.

We often look to schools and universities as places where inquiry and debate can take place without degenerating into pitched battles, but the words culture war are linked to higher education. Over the last thirty years, culture warriors have made colleges and universities a prime site for their battles. Recently, even teaching critical race theory and other topics that make people uncomfortable have been banned, and state governments have threatened faculty and funding.

How should a university respond? Faced with culture war, I suggest to you today we should practice culture peace by defending our missions and our most valuable members. The missions of colleges and universities differ in subtle ways, but they all require broad freedom of inquiry and expression. This means that politically unpopular perspectives should be explored thoughtfully by students and faculty, and that conversation and debate should be guaranteed within safe enough spaces—environments in which everyone is protected from harassment and intimidation, but no one is protected from being offended or having their minds changed. A place of freedom of inquiry is a place of experimentation—and that means that people will modify their views, discovering they have been mistaken. In such spaces, forgiveness and mutual understanding are at least as important as the courage to speak one’s mind.

During times of intense cultural conflict, higher education’s practice of culture peace must include the commitment to protect the most vulnerable members of its communities. At a time when inquiry into racism and its history are once again a wedge issue in the political arena, concern for the vulnerable means at some schools protecting faculty and student research into how aspects of our current conditions have been built on policies and customs that are unjust and morally repugnant. At a time when queer and gender fluid people are being scapegoated, at a time when women’s rights are being eroded, and in which racist and antisemitic threats are surging, practicing culture peace also means ensuring that a campus is a place where all can thrive. At many colleges, conservative and religious students find themselves marginalized, and the institution’s duty is not only to protect them from harm, but to ensure that they too can take full advantage of the educational opportunities the schools have to offer. This will include campus discussions on what intellectual diversity means in specific contexts—and support for programs that bring to these discussions serious views that may not be popular among the majority of students and faculty.

Now some would advise academics to just stay out of the way of conflicts raging around them—to strive for a neutrality that enables them to rise above the politics of our times. Others might think it naïve or idealistic to call on universities to practice culture peace when they themselves are under attack in this culture war. But I believe to be true to our academic and civic purposes, Wesleyan’s mission reminds us that we must become practical idealists, making peace where we can by promoting open inquiry and free expression. We must defend those who want to participate in this endeavor from threats of violence or marginalization while cultivating respect for intellectual diversity. By practicing culture peace, we will be more open to discovery, including the discovery that it’s time to change our minds and listen more carefully to others. Practicing culture peace at a time of culture war is not easy; but in the long run, it’s the antidote we need to today’s cultivation of outrage and conflict.

Over these four years, I’ve gotten to know many of you in my classes, in student government, and even in a few demonstrations. In your courageous company, I feel we may well be able to reject the cynical status quo that mobilizes rage, that we may be able to build a politics and a culture of compassionate solidarity rather than one of fear and divisiveness. As I say each year at Commencement, we Wesleyans have used our education for the good of the world, to ourselves be changemakers lest the future be shaped by those for whom justice and change, generosity and equality, diversity and tolerance, are just too threatening. We know that you will find new ways to make connections across cultural borders—new ways to build community. When this happens, you will feel the power and promise of your education. And we, your Wesleyan family, we will be proud of how you keep your education alive by making it effective in the world.

It’s been nearly four years since we unloaded cars on an ungodly hot day then too here at the base of Foss Hill, four years since parents shed a tear as they left you here on your own. Seems to me like a short time ago. Now it’s you that are leaving us, but remember no matter how on your own you feel yourselves to be out there, you will always be part of the Wesleyan family. Wherever your exciting pursuits take you, please come home to alma mater. Come home often to share your news, your memories, and your dreams. Thank you and good luck to you!