New Database Shows Court Changes that Impact Access to Justice

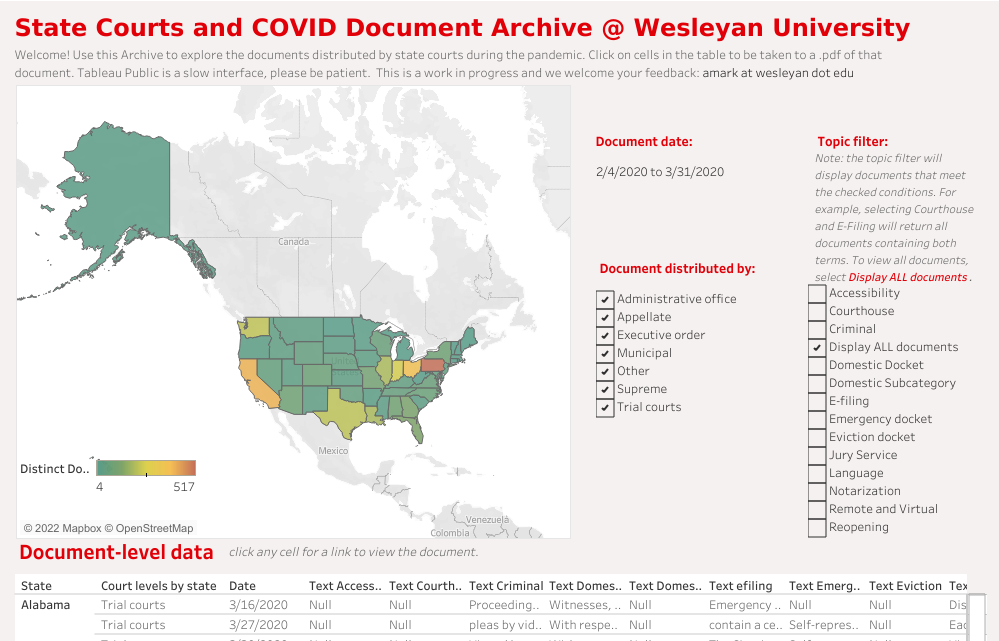

A new database created by Alyx Mark, assistant professor of government, documents the often mundane, yet vitally important changes courts made to their policies and procedures over the course of the global pandemic, changes that directly impact ordinary people’s access to justice.

“We have 51 judiciaries – 52, if you count the federal system – and they are their own special unicorns. They all have different structures. They all have different personalities … they all approach their administrative roles and big policy questions in such different ways,” Mark said.

The pandemic allowed Mark to examine how state courts make policy about how people access them. “We wanted to know: Who was sending out guidance and orders? About what, when, and through what channels? We used (natural language processing) techniques to take a first crack at sorting the documents according to these characteristics,” Mark said on a Twitter thread.

Mark worked with Professors Pavel Oleinikov and Valerie Nazzaro of Wesleyan’s Quantitative Analysis Center to create an online tool to analyze more than 20,000 court orders from the first year of the pandemic. The project was supported by the National Science Foundation and the Pew Charitable Trusts.

“I hope it serves to equip courts and justice advocates with tools to help them understand what works and what didn’t during the pandemic,” Mark said.

A court in 2019, before the pandemic, was likely to operate the same way it did decades ago, Mark said. COVID-19 forced the courts to update their procedures and consider how best to serve its constituents. “In a recent article by Richard Susskind, he asks ‘Is court a place or is court a service?’ If you start thinking about court as a service, you have to start thinking about designing it in a very different way,” Mark said.

How a court chooses to regulate itself isn’t always obvious. If a court makes a decision in a case, the decision is documented and if there is an appeal, a higher court renders further verdict. A public paper trail is made. Changes to the day-to-day logistics of a court – whether a document needs to be notarized or simply requires an e-signature, to give an example – are not made through that same process. It can be difficult, if not impossible, for a regular citizen to know when changes to case processing occur and how those modifications affect their own access to justice.

The language used to describe how to engage with the court can be complicated. Websites can be poorly designed or difficult to navigate. All of these things make it hard for the average person to have their civil or criminal concerns addressed. “We are just beginning to understand the ramifications,” Mark said.

The main change to court proceedings during the pandemic came when they were allowed to happen remotely. On the one hand, thanks to the technology, judges say far fewer people default on attending their hearings. On the other, the virtual realm created its own problems for people who didn’t have access to the internet, or those for whom digital literacy was an issue. The main question, as the pandemic moves into an endemic phase, is whether courts continue to offer remote accessibility, Mark said

In addition, the pandemic also allowed courts to set different priorities in terms of what proceedings need in-person hearings and traditional processes. Mark believes that courts can increase accessibility through innovations like remote hearings and eviction diversion programs. “If you make it easier for people to solve these problems, perhaps they’re going to burden social services less than they did before. If you make your court run more smoothly, you might be saving your community money,” Mark said.

Mark will share her findings, along with documentation and interviews of court officials, in a new book that is due to be published in 2023. “The pandemic gives us this snapshot of activity that is typically under the waterline for us. It’s gives us an opportunity to think more carefully about how power is distributed in state courts,” she said.