Research Inspires New Gallery Exhibit

Professor of Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Victoria Pitts-Taylor’s 2016 book The Brain’s Body: Neuroscience and Corporeal Politics has inspired a group of painters to offer their own artistic impressions of her complex ideas in a new gallery exhibit.

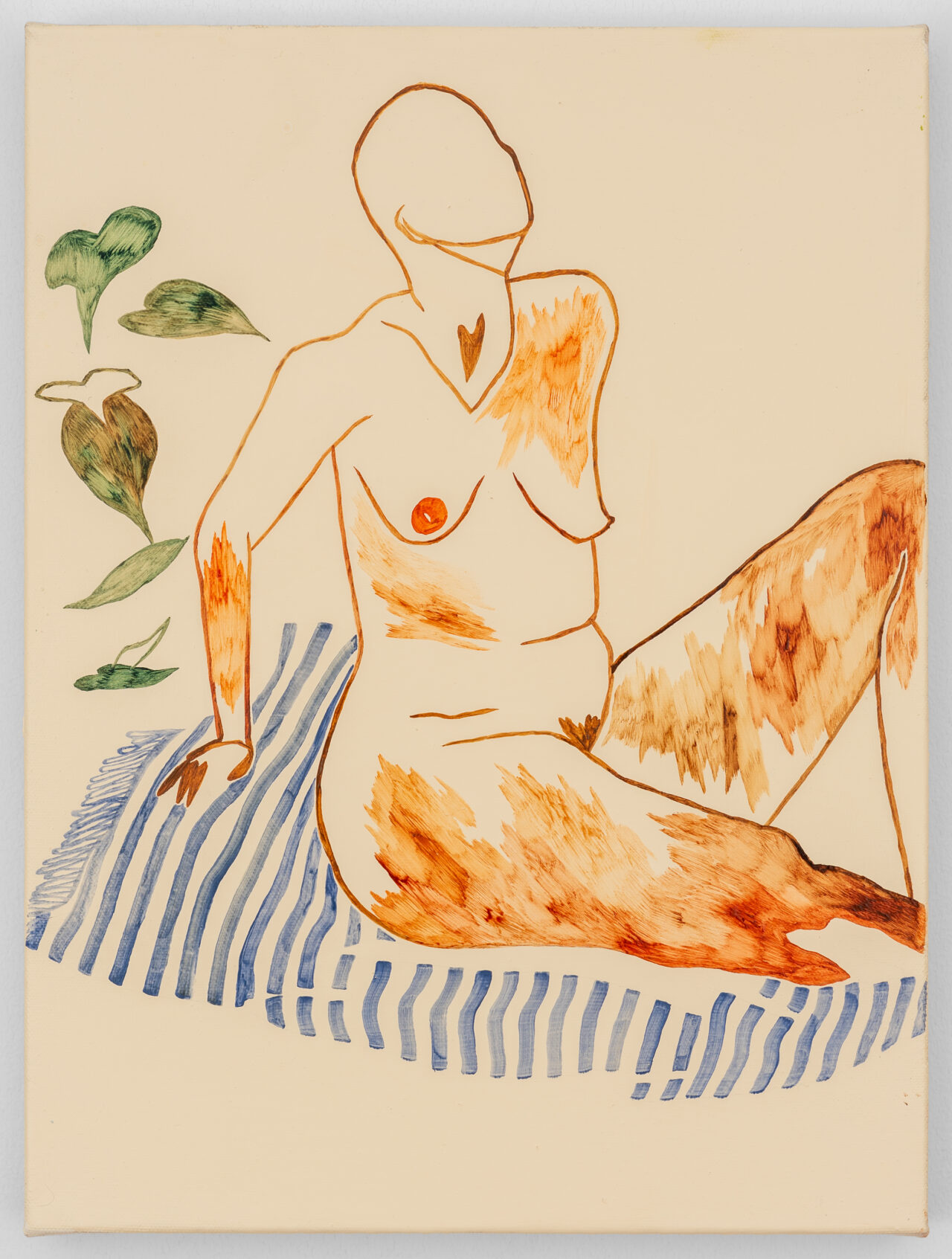

The exhibit, called “Somatic Markings,” is on display through December 23 at the Kasmin Gallery, located at 297 Tenth Avenue in New York City. The exhibit features seven international artists employing the nude figure to grapple with issues of contemporary corporeal politics, according to the gallery’s press release.

“A lot of the motivation behind the show was to push beyond a simple interpretation of figurative painting as a statement on ‘identity,’ which is a somewhat vague term often overused in art writing. Looking to what informs this concept of identity, from the social and environmental causes to the actual mechanics of the brain, I think helps deepen and define a lot of what these artists are trying to express,” said Hannah Tracy, curator of the exhibit.

Tracy was interested in the concept of art addressing contemporary corporeal politics, and was curious what sort of cross-disciplinary texts might already exist when she discovered Pitts-Taylor’s publication. Pitts-Taylor mines feminist and critical theory to discuss how the brain interacts with and is impacted by social structures like race, gender, class, sexuality, and disability.

Specifically, Tracy found Pitts-Taylor’s discussion of how neuroplasticity helps provide an alternate explanation to the sexed brain, and how gender and sexuality may be understood as performative, particularly interesting because many artists are playing with concepts of gender. “I realized the act of painting itself is inherently a performative, embodied experience,” Tracy said.

Some of the works were created specifically for the show, while others were extant. “As I was reading Prof. Pitts-Taylor’s book, I simultaneously read in an interview with Shadi Al-Attalah, one of the artists in the exhibition, that they were interested in the concept of embodied cognition, which is one of the theories Pitts-Taylor discusses, so it felt like this great moment where these ideas were coalescing all at once,” Tracy said.

Pitts-Taylor was pleasantly surprised by this particular reaction to her research. She’s used to the more conventional ways academic work inspires other ideas – through being cited in in other research or being asked to respond to dissertations on topics covered in her work. Seeing the paintings awash in color, vibrant and alive, gave her a new sense of what her work could mean.

“It’s hard to put into words. I’ll say one thing that strikes me is how personal these cultural and political issues are. The art renders the topics that I’ve studied in really intimate detail. It brings it to a level of intimacy you don’t get with scholarly discourse … (the art) reaches people at a different level,” Pitts Taylor said.

Both Tracy and Pitts-Taylor see how an interdisciplinary approach can yield novel insights – the forms speak to each other in exciting ways. “Ultimately, I think artists and scientists are both trying to make sense of an increasingly complex world, albeit through very different approaches. I think oftentimes people don’t “get” art or “understand” science because the former often lacks a grounding framework, and the later lacks emotive connectivity. Pairing them together I think helps fill in those gaps beautifully,” Tracy said.

“I think some of these areas of research are tremendously fruitful, have always been interdisciplinary and lend themselves to work with and in dialogue with the arts,” Pitts Taylor said. “(Scientists) communicate ideas in a different vein with a different vocabulary and a different set of tools, so visual art can absolutely broaden and enhance the thinking on these topics.”

The notion that different disciplines have something to say to each other and that their dialogue can help us grow as people is crucial in our divided and divisive culture, Pitts-Taylor believes. Conversations where science jumps into the field of artistic exploration, and vice versa, are precious and shouldn’t be taken for granted.

“We are seeing a huge crisis in American democracy. The attacks on democratic ideals are also attacks on the kind of political and cultural work, scholarship, and conversations happening around gender and sexuality and race and ethnicity, so I think that support for the arts that takes up these themes is probably endangered, not at Wesleyan, but across the country,” Pitts-Taylor said.

oil on canvas , 16 1/8 x 12 1/4 inches, 41 x 31.1 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Kasmin, New York.

88 5/8 x 126 inches, 225 x 320 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Kasmin, New York.