Revisiting Martin Luther King’s First Visit to Wesleyan

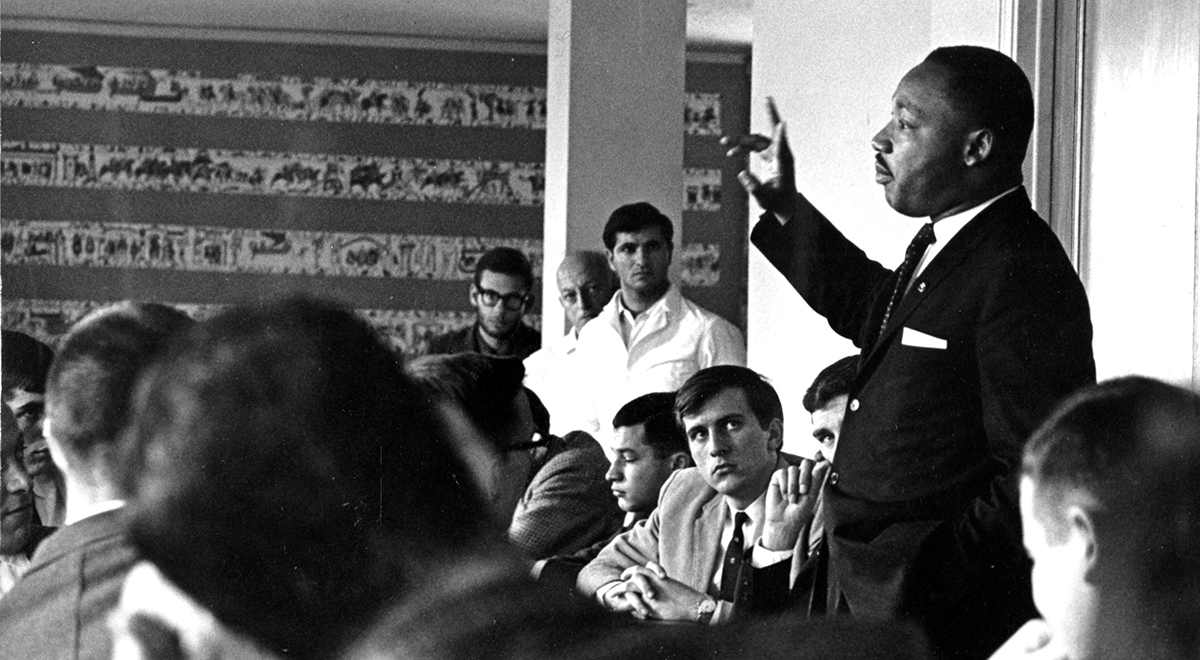

When he came to Wesleyan University’s campus on January 14, 1962, many people thought Civil Rights leader Martin Luther King Jr., Hon. 64, was in a moment of defeat. Uncharacteristically for King, the Albany Movement, which he helped lead after it was started by protestors, struggled to gain a foothold in the media. But if King were feeling defeated, no one could tell by the impassioned address he gave before interested students and faculty.

In December of 1961, many protesters were arrested in Albany, Georgia and intentionally declined bail to attempt to crowd jails and spotlight inhumane conditions. However, Albany sheriff Laurie Pritchett prepared local jails and spread those arrested throughout the region, suppressing much of the movement’s plans to gain media traction, said Ashraf Rushdy, Benjamin Waite Professor of the English Language, African American studies, and feminist, gender, and sexuality studies.

“The movement, then, wasn’t able to inspire the kind of media coverage that they had earlier drawn because of the violence of the police and the conditions of the jails,” Rushdy said. “That moment, at least superficially, appeared to be a defeat for the kinds of social changes Dr. King was hoping to institute.”

It wasn’t just a story of failure, though, Rushdy pointed out the tremendous resilience and organizational planning efforts demonstrated by protesters. Despite the difficulties of the moment, King was still touting the successes of the movement to that point when he came to Wesleyan on the eve of his 33rd birthday. King joined hundreds for a sermon in Memorial Chapel and later led a rally in a former athletic building monikered “The Cage.”

“We’ve seen the walls of segregation gradually crumble in our day and in our age,” King said, according to Wesleyan Argus coverage of the day. He highlighted that poll taxes were nearly eliminated throughout the country, Black voter registration was rising, and progress was being made in “economic justice.”

There was still much progress to be made, though. King called for then President John F. Kennedy to declare “all segregation unconstitutional on the basis of the 14th amendment” to the U.S. Constitution. At a rally in a former Wesleyan athletic building, he urged the federal government to legislate. “It can’t make the white man love me, but it can keep him from lynching me,” King said.

He also preached for peace, a main tenant of his message to the masses throughout his advocacy and a contributor to his legacy. “Moral ends will be achieved through moral means,” King said.

Wesleyan Honors King Through Peaceful Activism

“Dr. King’s legacy is and remains deeply important, and on this day we celebrate his life and accomplishments, we should perhaps keep in mind two ideas in which he deeply believed,” Rushdy said. “First, justice is more important than appeasing false allies. Second, while he is the perceived figurehead of the movement, we must remember the masses, especially the masses of African American women who made the movement possible.”

Rushdy said King’s stance against the Vietnam War “cost him much” in regarding to President Lyndon B. Johnson’s support for the movement, but “what it gained him was beyond valuable.”

He also mentioned a sermon King delivered months before his assassination in 1968. King identified true leadership as having to do with love, compassion, and concern for others, not just standing in front of the masses “but serving them from wherever one stands,” Rushdy said.

“That spirit was exemplified by those activists, especially the women who took equally principled stands on justice, who don’t have days dedicated to them, but who made that day—and so many other more important things—possible,” Rushdy said.

Now 61 years after his first visit to campus, the energy to act that King tried to breathe into students and faculty still lives on this campus. Wesleyan has always been a community that is active in the public sphere, from the Civil Rights movement to student marches during the Vietnam War to participation in E2020 ahead of the 2020 election.

“There is a long history of student protest in this country,” President Michael S. Roth ’78 wrote in a piece for the Los Angeles Times. “And today’s demands from students for greater diversity and inclusion—among the faculty, in admissions and in what’s taught in the classroom—fall within that tradition. Back in the day, students raised their voices against apartheid and more recently have demanded concrete action to deal with the climate emergency. Students have pushed higher education to live up to the ideals we claim to espouse, and in so doing they have learned how to constructively respond to political differences beyond the campus.”

Now ahead of the 2024 election, Wesleyan is again focused on engaging students in civic life, by hosting the Democracy in Action Convening on Feb. 16 and 17. The Convening explores the relationship between higher education and democracy by tackling topics at the intersection of universities and civic life. In a recent article for Salon, Roth wrote, “By defending democracy, we will deepen learning; by deepening learning we will defend democracy. Both will make our educational institutions more effective, and this will create a virtuous circle of civic preparedness for the country as a whole.”

Documentation of King’s visits to campus can be found in the Olin Library archives. Additional photos of his visits to Wesleyan are below. (Photos courtesy of Special Collections and Archives)