Professor Studies How Black, Immigrant Outcasts Become WWI Heroes, but still Return as Outcasts

|

|

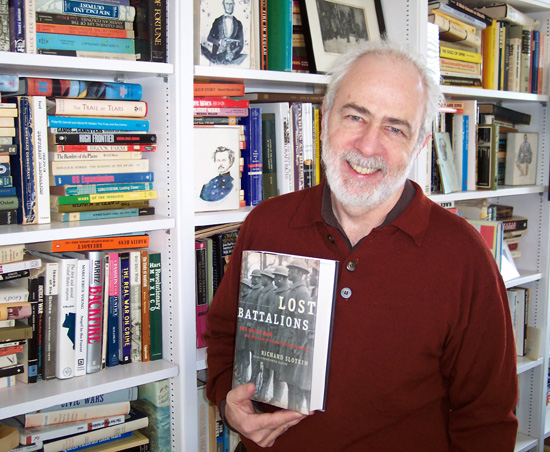

Richard Slotkin, Olin Professor of English, professor of American Studies, studied the 369th Battalions and 77th Divisions roles in France for his latest book, Lost Battalions: The Great War and the Crisis of American Nationality.” |

| Posted 12/19/05 |

| In 1918, the United States loaned its all-black 369th Infantry Regiment to fight under the French flag in World War I. These soldiers, rejected for combat duty by their own country because they were black, fought for 191 days, longer than any other American unit in the war. The Harlem Hell Fighters, received an honorable award for bravery from the French. In their heroic attack on Sechault, of some 2,500 riflemen who began the battle only 700 survived unhurt.

They kept fighting until they couldnt fight anymore, Slotkin says. Their efforts were extraordinary. Studies of combat psychology show that no person can handle more than 180 days in combat, and they fought for more than 190 days. Twenty miles away, 700 New York immigrants forming a battalion of the United States 77th Division, or ‘Melting Pot Division’ crossed German lines and advanced into France’s Argonne Forest. This unit of Jewish, Italian and other eastern Europeans battled for six days with limited ammunition and supplies, food, water and shelter. They refused to surrender, although their unit was completely surrounded. Only 200 survived. Richard Slotkin, Olin Professor of English, professor of American Studies, has spent the past four years extensively researching the 369th Battalions and 77th Divisions roles in France. His latest book, Lost Battalions: The Great War and the Crisis of American Nationality, published in December 2005 by Henry Holt and Co., depicts American black and immigrant soldiers who were considered to be lesser citizens and racially inferior during and after the war. In 1917, one in three people living in America was from a foreign country or had a foreign-born parent. Although the U.S. government would have preferred to send only white, American-born citizens to combat, immigrants were promised equality in return for their loyal service in the war. During World War I, we had to raise an army of 2 million men overnight, and we could not play this role without having minorities involved in the war, Slotkin explains. The government basically told these Blacks and immigrants that if you go to war, we will accept you. The U.S. had to look at how all men are created equal in a way that never existed before. Some of these guys were from Germany or Austria and could have taken an exemption from being in the war, but they wanted to show their American patriotism, Slotkin explains. But when they came back to the U.S., they still got the shaft. Congress identified them as races incapable of full Americanization, banned further immigration and signalled acceptance of ethnic discrimination. The U.S. also broke its promise to the Blacks. The Army gave the French a Secret Information Concerning Black American Troops, which demanded the adoption of strict racial separation. The document stated that it was essential that Frenchmen understand that to Americans, displays of interracial friendship were deeply offensive. It declared that friendships would encourage intolerable pretensions to equality, which would pose a danger to Americas civil peace when the troops came home. Slotkin studied World War I unit histories written in books and published on microfilm. He visited the National Archives to study World War I military books, and hired research assistants, one of which translated Yiddish newspaper clippings for the project. He focused his research on the lives of about two dozen characters, including the Lost Battalions captain Charles Whittlesey, who was named a recipient of the Medal of Honor, the highest award given by the U.S. Army following the war. Whittlesey is also the main character in the Arts and Entertainment movie titled Lost Battalion from 2001. Slotkin says the movie portrays an accurate depiction of the events that occurred between Oct. 2-8, 1918. The author says history buffs and scholars would be interested in his research, although the story is written in a way that can appeal to the general public. The History Book Club and Military Book Club have both accepted Slotkins book into their listings. A recent Publishers Weekly Starred Review states that Slotkins story examines the relationship between war and citizenship in this trenchant, gracefully written military and social history. Slotkin smoothly telescopes from the trenches to the political and social implications for decades to come in this insightful, valuable account. Stories like these havent been taught in schools because Americans dont like to look at how hard it has been to become a multicultural nation, Slotkin says. Slotkin is the author of seven other books including Abe: A Novel of the Young Lincoln, Gunfighter Nation and Regeneration Through Violence. He is a National Book Award Finalist and winner of the Albert J. Beveridge Prize. |

| By Olivia Drake, Wesleyan Connection editor |