5 questions with … Neely Bruce

The following is the second installment of The Wesleyan Connection’s new feature, “5 Questions.” This issue, accomplished composer and Wesleyan Professor of Music Neely Bruce is our guest.

Q: I see your piece Vistas will be performed at the “Hearts Pounding and Skins Taut” concert in late October at Wesleyan. For what instrument was this piece originally composed?

NB: Vistas at Dawn is a short (approximately three minute) piece for organ and vibraphone.

Q: For what musician did you compose this piece?

NB: I wrote it for Ronald Ebrecht, Wesleyan University Organist, to play. Over the years I’ve written two major works and several smaller pieces for him. Ron has been a staunch advocate for new music for the organ for years, and has encouraged his faculty colleagues and our students to write all sorts of music in all sorts of styles for that remarkable instrument. This has been going on for more than 20 years, and dozens, perhaps hundreds of new organ works have seen the light of day because Ron asked people to write them and offered an opportunity to get them before the public. Vistas was originally written for a tour that he did in Russia with a Russian percussionist, although he’s played it many times in the US with several different vibes players, including Wesleyan’s own Jay Hoggard. It’s something like a pop ballad—slow, languorous, very chromatic, sometimes almost atonal, sometimes with jazz-like quasi-standard chord changes.

Q: Aside from hearing Vistas at the Center for the Arts in October, where can people see you perform publicly this fall?

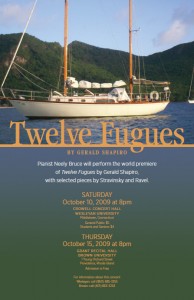

NB: October is an exceptionally busy month, even for me. I’m playing the world premiere of Twelve Fugues by Gerald Shapiro, chair of the Music Department at Brown and one of my closest friends. (Shapiro and I were freshmen together at the Eastman School of Music). I’m playing these pieces at Wesleyan’s Crowell Concert Hall on Saturday October 10 at 8 p.m. and at Brown on October 14, with a little Stravinsky and Ravel as the warm-up. The Bill of Rights: Ten Amendments in Eight Motets is being performed at Mitchell College in New London on October 20. For Hearts Pounding and Skins Taught I’m performing one of my more extravagant piano pieces, a random shuffle of four-note phrases entitled Furniture Music in the Form of Fifty Rag Licks. Elizabeth Saunders is singing all-Ives concerts that I will accompany—for one of my classes next week, then on November 1 at The Hopkins School in Hamden. Additionally, there may be a third Ives event later in November. There are also auditions in New York for Flora (see below). Whew—I’m slightly dumbfounded just writing this all down! I need to put something about all these things up on my website.

That sounds exciting. Members of the Wesleyan community look forward to filling up their calendars by listening to your music.

Q: Is the public welcome to attend the Bill of Rights concert? How many times has your Bill of Rights composition been publicly performed and how does it feel to hear this patriotic piece of yours performed for large audiences?

NB: The public is cordially invited to attend—and I hope thousands of them do! So are my friends on Facebook, for whom I sent up an event page. We should get a good crowd from the immediate area. I have a spy in the chorus, who called me last night to say that rehearsals were going very well—that was welcome news. I’ve also gotten together a contingent of students, friends and area singers to help the Mitchell College students out. Anyone who reads this who wants to sing—get in touch with me by writing nbruce[at]wesleyan[dot]edu. The more voices the merrier.

This will be the fourth complete performance of The Bill of Rights. (There was a public reading at South Church in Middletown in the summer of 2005, the official premiere at Wesleyan that fall, and a performance in 2006 at the Unitarian Church in Hamden.) There have been dozens of performances of my setting of the First Amendment, all over the country, including one that you can see on YouTube. As far as the feeling goes—hearing your own music sung or played is always pleasant, unless the performance is really awful. But hearing these powerful, formative, urgent texts—ringing 18th-century prose, so majestic to read aloud and so lasting in the memory—sung to one’s own music is a special thrill.

Q: I heard that you are working on recreating the historical dance music for an operatic piece from colonial era America. How do you begin to reconfigure the popular dance music of so many years ago and how did you first become involved in this exciting project?

NB: The first ballad opera done in the colonial US—and the first professional piece of musical theatre done in English-speaking North America—was a popular import from London called Flora, or, Hob in the Well. It was produced in Charleston in 1735 and revived the following year at the newly-constructed Dock Street Theatre. The most famous ballad opera is of course The Beggar’s Opera, but in its day Flora was also quite a hit. Long-lived, too. The text remained in print until the 1850s. Ballad operas used preexisting tunes (folk songs, popular ballads of the day, etc.) sung to newly written words specific to the drama. For Flora, 24 of these tunes survive—something like 18 pages of music, in two different, slightly conflicting versions. My job is to edit the tunes; write accompaniments, including introductions and codas; compose the dance music; write all music for set changes, entrances and exits, special moments (there’s a big fight, for example); and the overture. I’ve finished all of the vocal music and begun the various incidental pieces. I’ll do the overture last. The complete score (voices, chorus and chamber ensemble of eight instruments) has to be delivered early next year.

Recreating the dance music of the early 18th century is actually a piece of cake, because it’s still being played today, all over the English-speaking world, for country dances, fiddling conventions, etc. Writing new music in that style is also something that people still do. The vocal music is more of a trick, and there’s no short answer to that part of the question! I should write a blog about this for my web site after the composition is done.

I don’t mean to be coy about the source of this commission, but it hasn’t been officially announced, even though I have to deliver the vocal score on November 1st and the production is about to be cast! I can say it’s being produced in the summer of 2010 at a major festival, and the announcement is forthcoming, around New Years.

I don’t mean to be coy about the source of this commission, but it hasn’t been officially announced, even though I have to deliver the vocal score on November 1st and the production is about to be cast! I can say it’s being produced in the summer of 2010 at a major festival, and the announcement is forthcoming, around New Years.

The way I got the gig is mysterious, and actually I know very little about how I was chosen. What I do know—I got a call out of the blue asking if I might be interested in being the composer/music director for this project. I said “yes” on the spot. A lengthy email correspondence ensued. Then there was a long process of being vetted, then there were negotiations about the timetable and of course the money, and finally there was a contract. And you’re right—it was very exciting.

Professor Bruce, thank you very much for taking the time to speak with me during this incredibly busy season. We all look forward to hearing more about your compositions—especially those that are being created as we speak!