Greenwood, Colleagues Debunk Sloshy Lunar Theory

James “Jim” Greenwood, assistant professor of earth and environmental sciences, and four colleagues have published a paper that casts doubt on the theory of abundant water on the moon while simultaneously boosting theories around the creation of the moon, several billion years ago.

The paper, “The Lunar Apatite Paradox,” published March 20 in the prestigious journal Science, stems from work involving the mineral apatite, the most abundant phosphate in the solar system. (Along with its presence on planets, it’s found in teeth and bones.)

Initial work on the lunar rocks brought back to Earth by the Apollo missions indicated that the Moon was extremely dry. Any evidence of water was dismissed as contamination from Earth.

But more recent experiments have shown the presence of plenty of water in grains of apatite derived from lunar rocks. Greenwood and colleagues sought to figure out whether, or how that could be.

“We formulated a solution to the problem of how you get this much water into moon apatite by using a mathematical model,” Greenwood said.

What the scientists found, by simulating the formation of apatite, was that the chemical evidence found in the apatite is consistent with magmas from Earth. This lends credence to the theory that a Mars-sized celestial body named Theia slammed into the then-forming earth, creating a ring of dust and gas that accreted, becoming the moon.

Greenwood’s enthusiasm for planetary geology is obvious even to first-year students in his class “Mars, Moon and Earth,” so named because “they’re my three favorites in the solar system,” he said.

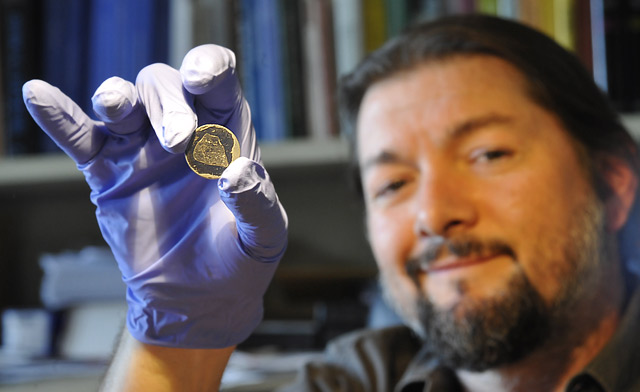

In his petrology classes, students using glove bags and microscopes can study moon rocks up close. Like him, they can work with “things I can touch and feel and work with, and use our earth instrumentation to analyze,” he said.

Along with lead researcher J.W. Boyce and three others, Greenwood presented the paper last week at the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference in The Woodlands, Texas.

The journal Science is estimated to be read by 1 million people around the world, and is extremely selective in publication. Only about 10 percent of submitted papers are chosen for the journal.

Read more about Greenwood’s research in this past Wesleyan Connection article.