Two Whistler Drawings from DAC to Be Featured in PBS Documentary

Two drawings by James McNeill Whistler, part of the Davison Art Center’s collection of more than 100 Whistler works, will be shown in a new documentary on the life of the painter.

The sketches, one in pencil and one in pen and ink, will be seen in “James McNeill Whistler & The Case for Beauty,” premiering September 12 on PBS.

They represent just a small part of Wesleyan’s extensive holdings of works on paper by Whistler, one of the most important American artists of the 19th century.

“Whistler was crucial in making the connection between the Impressionists and British art, and … American art,” said Clare Rogan, curator of the Davison Art Center and adjunct assistant professor of art history. “While he worked mostly in Europe, he was incredibly important in creating that link.”

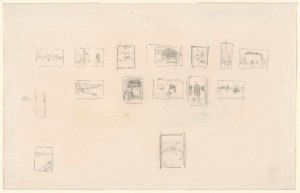

Neither sketch is large – unlike finished prints or paintings, both were for Whistler’s personal use and not intended to be seen by a larger audience. They are, however, interesting glimpses of an artist at work. The pencil sketch, measuring at just 4.4 by 6.9 inches, represents his ideas about displaying his famous landscape prints of Venice at an 1880 exhibit by the Fine Arts Society in London.

In 1879, Whistler had declared bankruptcy and fled London for Italy, eagerly accepting a commission from the Fine Arts Society for a set of views of Venice. When he returned to London in late 1880, he intended the exhibition to be a triumphant return to the center of artistic life in London, according to Rogan.

“This drawing shows his meticulous planning for the layout of the exhibition, which ultimately yielded few sales,” she said. “Nevertheless, the First Venice set ultimately influenced generations of artists and collectors.”

The pen and ink sketch, “Harmony in Flesh Color and Pink,” showing a woman in the large hat and bustled dress typical of the Gilded Age, is also small, about seven by four inches. It is also called “Sketch of Lady Meux,” and is related to an oil painting of a wealthy brewer’s wife commissioned in 1881 (and now in New York’s Frick Collection). Whether it is a preparatory drawing for the final work or one sketched afterward (perhaps in response to Henry James’ reported comment in 1882 that “her hat didn’t fit”) is unclear, Rogan said.

“The interesting thing about the choice of these two drawings is that it shows the depth of the Wesleyan collection,” Rogan said. “Not just in the finished master works, but in the context of how things are created, how (artists) organize their thoughts and ideas.”

That is one reason why Rogan makes wide use of the Whistler works in the DAC when she teaches history of prints and other classes. “You can see the artist’s mind at work,” she said.

Whistler was born in Massachusetts, but grew up in Russia, where his father was an engineer working for the Czar. He returned to the United States as a young man, eventually dropping out of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, but spent much of his working life in Europe, where his circle included many prominent intellectuals and artists of the time. While he is perhaps best known for his large oil paintings, including the portrait of his mother, he was an influential maker of prints as well, and engaged and encouraged several generations of collectors.

Both drawings were gifts of George Davison (B.A. 1892), in the years between the 1930s and 1953. Of more than 100 Whistlers held by the art center, about 90 were from Mr. Davison’s collection.

A banker in New York, Davison, the greatest benefactor of the DAC collection, began collecting prints in about 1907. Beginning in the 1930s, he gradually gave his collection of some 6,000 prints to Wesleyan. In 1952, the year before he and his wife, Harriet Baldwin Davison, died, they supported the establishment of the art center in an addition to the historic Alsop House. They were also the donors of a superb collection of rare books to the university, and funded the creation of the Rare Book Room at Olin Library.

To learn more about the film, go here.