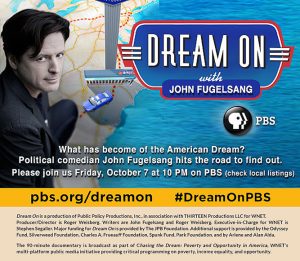

Award-winning Documentary ‘Dream On,’ by Roger Weisberg ’75 Airs on PBS, Oct. 7

Dream On, the newest documentary by Roger Weisberg ’75, will air on PBS at 10 p.m. Friday, Oct. 7. (check local listing). The film is the 32nd documentary written, produced and directed by Weisberg, who heads Public Policy Productions. Dream On has already appeared in 19 international film festivals, garnering four top awards. Weisberg’s earlier works have won more than 150 awards, including Emmy and Peabody awards, as well as two Academy Award nominations.

Dream On, the newest documentary by Roger Weisberg ’75, will air on PBS at 10 p.m. Friday, Oct. 7. (check local listing). The film is the 32nd documentary written, produced and directed by Weisberg, who heads Public Policy Productions. Dream On has already appeared in 19 international film festivals, garnering four top awards. Weisberg’s earlier works have won more than 150 awards, including Emmy and Peabody awards, as well as two Academy Award nominations.

Dream On asks the question: “Is the American Dream still alive and well?” Are we still optimistic that hard work will raise our standard of living—for our generation and for our children? Weisberg explores this question with political comedian John Fugelsang serving as host and commentator throughout this unusual road trip. The journey revisits the cities of Alexis de Tocqueville’s 1831 itinerary, which served as the Frenchman’s research for Democracy in America. In it, Tocqueville described America as a land of equality, opportunity and social mobility. For those interested in viewing the film as part of a community screening event or classroom educational opportunity, PBS offers a viewer’s guide, as well as a trailer and additional resources, including video segments that Weisberg was not able to include in the 90-minute slot for PBS.

Weisberg also spoke to The Wesleyan Connection about the process of creating his newest work and his hopes for it:

Connection: What was the inspiration for Dream On?

Roger Weisberg: I wanted to make a contribution to PBS programming surrounding the election, but I wanted to do it in a way that was different from some of my more conventional reporting on poverty, social mobility and economic inequality. The road trip infused this project with a degree of exuberance and levity, while also permitting us to examine some urgent social issues and meet some really powerful subjects along the way.

Connection: How did John Fugelsang come to join you?

RW: We were pretty lucky to have been referred to him by colleagues who worked with Bill Moyers. It turned out that for John, the timing was perfect: He’d just lost his job as a talk show host, because the cable network that had hired him was sold to a foreign buyer. Because of John’s new feeling of economic insecurity, he was able to put himself in the shoes of many of the people he met on our Tocqueville odyssey.

Connection: What kind of time frame were you working in?

RW: In the early part of 2013, I did the whole road trip on my own, without a crew, to meet prospective participants and scout locations. In the fall of 2013, we filmed this journey in two stints of about 25 days each.For the balance of the year, we organized the footage and then began editing January of 2014. It took us a full year to edit the piece. We initially had aspirations for a four-part series, because we filmed so much great material. A lot of that footage is up on the PBS website, because it couldn’t make it into the 90 minutes that PBS had allotted for the broadcast.

Connection: How did you find your subjects?

RW: My entire career has been about this key question: How do you find people whose stories are critically important but who seldom make it to the screen? For Dream On we had prototypes in mind for the stories we wanted to highlight—and I always ask myself, “Who is going to come into contact with these folks?” And sometimes it’s labor unions, and sometimes it’s social service providers, or advocacy groups. Sometimes we go through a corporate communications office to get access to employees. Or if we’re looking for a high profile expert, there are invariably gatekeepers to approach in order to reach the people we want.

Connection: You find people who speak frankly about personal issues in front of a camera. How do you create the environment that enables them to talk with such honesty?

RW: Some of that intimacy and candor come from the time I spend with the subjects before cameras are involved, and some of it simply comes from showing them the respect that they deserve. Some of the honesty and authenticity also come from giving people a voice when they have felt powerless and voiceless. They know we are not judging them; we are giving them a chance to share their struggles and their dreams for the future. We let them know that what they have to say is valued—and I think that can be very affirming for people, even when they are sharing some very painful parts of their life

Connection: When you speak to the single mother who had been a battered wife, you show her family as it was when her 20-something kids were toddlers. Where did this footage come from?

RW: That old footage came from a film I made in 1995, Ending Welfare As We Know It. Social mobility is often measured across generations, and you only know if there’s any kind of upward mobility when you compare people’s economic status with that of their parents. So I had the unusual ability to dig into my film archive to to find people I profiled in earlier films in order to illustrate whether there had been any social mobility across generations over a period of more than 20 years.

Connection: And what is it that you’d like your PBS audience to grasp—and how would you like your Wesleyan audience to react?

RW: I suppose I’d like the Wesleyan audience to consider the privilege of our education and the doors that a Wesleyan degree can open for us—and the fact millions of young people, many of whom have comparable aptitudes and abilities, will never have those same opportunities because of structural barriers in place that prevent them from achieving their full potential.

We see the people we profile in Dream On every day, the people caught in low-wage service jobs, but we take them for granted—the people who serve us at restaurants, or clean our hotel rooms, or look after our elderly relatives. Dream On is a way of pulling back the curtain a bit and asking viewers to see what their lives are really like. The single biggest achievement we strive for is to get our viewers to empathize with the people on the screen.