New Book by Sachs ’97 Inspires Readers to Push Thought Boundaries

Ready to step outside your comfort zone? We recently spoke to Jonah Sachs ’97, who explores what empowers some people to respond to change with creative breakthroughs while the rest of us spend our lives clinging to the safety of “the way it’s always been done,” in his new book, Unsafe Thinking: How to Be Nimble & Bold When You Need It Most (Da Capo Press, 2018). Filled with ideas and tips on everything from embracing risk and inspiring unsafe thinking in conservative business cultures to bouncing back from failure, as well as a mix of brainteasers, experiments, and puzzles, Unsafe Thinking is both inspirational and entertaining—and the perfect springboard to your next big idea. Sachs is the award-winning founder and a partner of Free Range Studios, a brand and innovation company that transforms companies through unsafe thinking.

Q: What was your major at Wesleyan?

A: I was an American studies major. I didn’t know it at the time, but learning to observe and analyze culture was the perfect preparation for a creative life.

Q: What was your impetus for writing the book? Are you a former “safe thinker”?

Q: What was your impetus for writing the book? Are you a former “safe thinker”?

A: I started an advertising agency straight out of Wesleyan. It was experimental, wild, and fun, and we made some of the internet’s first viral video hits for social change. But as we grew, something unanticipated happened. I got anointed as an “expert.” I found myself on stages and in executive offices offering all sort of rules for creative success. I started having more answers than questions. I became fixed in a certain way of thinking. And as my company grew, I laid in more and more structure to make it manageable. Before long, I could see that the creative life was being sucked out of us. And while the company was still healthy on the surface, I knew if we didn’t get nimble again, we’d go over a cliff. I wanted to change, but the pull of what I knew—of safe thinking —was magnetic. I felt constantly trapped between a desire to act and a fear of it. So I started reading the science of what makes people creative and how they change, and I spoke to 100 innovators I admired. What came out of it was a set of ideas I now call unsafe thinking.

Q: What is “unsafe thinking,” and why should we practice it?

A: Unsafe thinking is the practice of challenging conventional wisdom, defying stifling rules, and risking disapproval so that we can pursue creative breakthrough. While it does sometime mean challenging the world, it most often means challenging our own thought patterns and habits. The world around us is changing quickly. And that means we’re challenged to change with it. If we’re relying on old lessons and routines, we are going to be made obsolete quickly. But change is hard—we’re creatures of habit. We love predictability and routine. We can only take so much risk. So I’ve explored how anyone can move toward that which makes us uncomfortable without flooding ourselves with risk and falling into exhaustion.

Q: You break down the process of unsafe learning into six steps or parts: courage, motivation, learning, flexibility, morality, and leadership. Courage includes getting past the fear of stepping outside the box or beyond accepted boundaries. How can we embrace anxiety and break the safe thinking cycle?

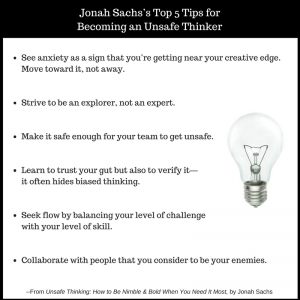

A: Anxiety is an absolutely natural part of the creative process. Even the boldest innovators I spoke to routinely feel fear in forging new paths. What seems to separate those who hide from change and those who thrive on it is how they respond to anxiety. Top performers reframe it. They tell themselves that anxiety is not a sign that they must retreat to a safer place. Instead they remind themselves that every creative thing they’ve ever done has begun with a feeling of fear. Anxiety is like a homing device. If you move toward it, you’re likely moving toward your creative edge.

Q: You discuss motivation in terms of mastering motivation and finding your source. How can we discover our motivation and use it to energize ourselves and others?

A: We often think that motivation comes simply from doing work we’re passionate about. That is, if you’re saving the world or finding your bliss, you’ll be motivated. It’s not that simple. Even the most purposeful work goes through stages that are just a slog. To keep us constantly focused and on the edge, there are some non-obvious things we can do. One of them is to work to stay in what’s called, in the psychological sciences, “flow.” When our level of skill is just below our level of challenge and we’re getting feedback from the environment on whether we’re succeeding or failing, we can stay focused and motivated almost indefinitely. You ever see someone playing a meaningless mobile game for hours with intensity? That’s flow. There’s no reason to take on that challenge, but that almost-perfect match of skill and difficulty keeps us hooked. We need to constantly assess whether we’ve got the right skills for the task. If we have too much skill for the challenge, we get bored. That’s a good time to motivate ourselves or our teams with extrinsic rewards like cash bonuses and prizes. When we have too little skill for the challenge, we start to shut down. That’s a good time to back up, build up skills, or bring on new collaborators who have those skills.

Q: One of the challenges of learning, as you see it, is maintaining an explorer’s edge without falling into the expert’s trap. Can you explain that challenge?

Q: One of the challenges of learning, as you see it, is maintaining an explorer’s edge without falling into the expert’s trap. Can you explain that challenge?

A: When you’re a beginner at something, you learn very quickly and your ego isn’t really attached to a single way of doing it. New, unexpected information isn’t greeted with skepticism or defensiveness, it’s just interesting data. You’re curious, motivated, and flexible. But as we become experts, we begin to identify with what we know. We form notions that there are right ways and wrong ways of doing things. We act quickly because we spot patterns instantly. This is great for chess where the board is two-dimensional and the rules never change. But it’s very bad for the complex challenges we face in business and life.

It’s silly to think we can just be rank beginners at everything. We should pursue knowledge and mastery. The problem comes in once we start thinking of ourselves as experts. We become fixated without realizing it. The identity of an explorer is a better one to take on. It means we’re passionate about new things and building mastery but we never claim to have arrived. One good way to be an explorer is to spend a bit of time consistently doing things you’re bad at. It humbles you, alerts you to new models of the world, and gives you great insights to bring back to your field. If you’re a computer programmer and you take a bread-making class, I guarantee you will start bringing baking metaphors into your coding that will open new paths forward.

Q: Focusing on flexibility, you talk about how to tackle difficult problems using unexpected solutions. How can we cultivate counterintuitive creativity?

A: Intuition is important. It lets us spot patterns and have creative insights. But intuition is too often a cover for biased thinking. We have an Aha! feeling about something, but that might just be because it looks like something we’ve seen before or it’s presented by someone with whom we work. That’s why there’s often so much opportunity in pursuing counterintuitive solutions. Find some piece of broken conventional thinking. Then imagine a solution that’s takes advantage of this knowledge. I spoke to some economists who realized that the old “teach a man to fish” adage is largely wrong. We don’t need to tell poor people what to do with money. In places where everyone lives on $2 a day, they know what they need. These economists started just handing out money through cell phone transfers, $1,000 at a time, to people in Kenya. The idea sounded insane, immoral to some. They’ve now raised more than $30 million and are considered one of the most effective charities in the world. They’ve forced the whole industry to rethink. “Teach a man to fish” sounds intuitively right to almost everyone. But that doesn’t make it right. Realize that and you gain a huge innovator’s advantage.

Q: Being creative sometimes means bending (or breaking) the rules. You cover this point under your chapter on morality. Can you explain why?

A: Rules are designed to protect the status quo, make things predictable, and drive efficiently from point A to point B. Creativity does the opposite. It’s good for organizations to have rules. Without them, the whole enterprise falls apart. But leaders need to understand that loyal, high-performing employees are, in fact, breaking rules all the time, often for the good of the company. It’s called “positive deviance.” In the public health world, we’re always looking for positive deviants in populations who have discovered solutions, so we can scale up those solutions. Leaders in organizations should do the same. They should encourage rule-breaking to be brought into the open, tell stories about rule breakers who found better ways, and adjust rules to take advantage of the insights these people have discovered. I also found that minimizing the sheer number of rules in an organization tends to open up space for more creativity.

Q: The role of leadership in unsafe thinking is to learn how to break consensus and infect others with the confidence to take risks. Why is this important, and how can leaders learn to do this?

A: Consensus feels good, but it leads us to narrow possibilities too soon and overcommit to paths that we should be perceiving as dead ends. To avoid this, leaders should stop speaking first to “set the tone” in discussions. When leaders speak first it lets the group know in subtle ways where the conversation is supposed to go and where it isn’t. A leader’s role is not to guide the discussion but rather to make sure that everyone in the room is sharing the important information that only they have. Ideas that aren’t widely known within a group are called information from the edges and they’re often the key to solving difficult problems. But unless we work to pull those ideas out, they get buried and forgotten.

Ironically, to get people to step into the zone of risk and innovation, a leader’s job is to make it safe enough to get unsafe. I spoke with Steve Kerr, the coach of the Golden State Warriors, and he helped me understand that his success came from drawing a hard line between the locker room and the arena. In the locker room, he worked to make sure everyone was given maximum psychological safety. He de-pressurized the work and made sure each player felt accepted and even loved as a human being. But on the court, he demanded top performance and risk-taking. This locker room/arena concept is, I think, very powerful for anyone looking to push teams into the unsafe zone. Make sure your people are secure and feel valued, then demand that they push themselves to their creative limit.

Q: You provide a plethora of good advice and illustrative case studies throughout the book. If asked to choose, is there a particular case study that, for you, brilliantly illustrates the benefits of implementing an unsafe thinking philosophy? In other words: What’s your favorite example and why?

A: The most fun story is probably that of Antanas Mockus. He became the mayor of Bogota in the 1990s when the city was the most dangerous in the world. He had this idea that to change behavior you can’t just punish people and crack down with more heavy-handed laws. You have to shock them out of their destructive behavior by breaking their expectations, incentivizing them in totally unexpected ways, and understanding how counterintuitive human motivation sometimes is. So when students threatened to riot on a university campus, he dropped his pants and mooned them. They broke out laughing and went home. He replaced the ineffective and corrupt traffic police that everyone ignored with “traffic mimes,” street actors who shamed law breakers and entertained onlookers. Traffic accidents plummeted. When he fired all the traffic cops, 400 applied for jobs as mimes. His “crime crackdown” involved encouraging citizens to commit symbolic acts of violence instead of real ones. He did this himself on national TV. And he introduced concepts of restorative justice even for violent crimes. Under his administration murders dropped by 70 percent.

Mockus faced intractable problems that couldn’t be solved with traditional, obvious tools. Rather than get stuck, he took this as an opportunity to innovate, and he came up with totally unique, unexpected, and powerful solutions. To me this is quintessential unsafe thinking.