Student, Alumnae Research Orphan Care In South Africa and Establish Aid Organization

|

|

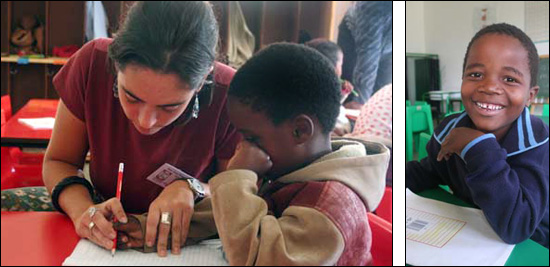

College of Social Studies majors Angela Larkan 06 and Lindsey Reynolds 04 raise funds and awareness for orphaned pre-schoolers in South Africa through their non-profit organization, Thembanathi. Larkan’s thesis at Wesleyan involved establishing a method of care for AIDS orphans using their school system. (Photos contributed by Maya Casagrande) |

| Posted 01/17/06 |

| Angela Larkan 06 was raised in an apartheid South African town knowing that she could have been born into a poor family just down the road. With an estimated one in three South African children expected to be orphans by the year 2010 due to the AIDS virus, Larkan always knew she wanted to make a difference in her native country.

When I look into the eyes of the orphans, they all seem to be telling me the same thing, says Larkan, who has family roots in South Africa reaching back to the 1800s. They show me that they matter as human beings; that they have energy, love and innocence to offer the world, and that they need someone to help them survive. In 2003, Larkan took on the task of co-founding a non-profit organization dedicated to raising funds and awareness for children in South Africa. The organization, Thembanathi, means “hope with us” in Zulu. Social studies major Lindsay Reynolds 04 has worked on and off in South Africa for the last three years on HIV prevention projects and co-directs Thembanathi with Larkan. According to the South African Department of Health, in 2004, South Africa had more HIV positive people than any other country in the world. In the province of KwaZulu-Natal, known as the AIDS belt, 40.7 percent of women attending antenatal clinics had HIV/AIDS. Mothers have a one in three chance of passing the deadly disease onto their children. Thembanathi partners with Holy Cross AIDS Hospice, a non-governmental organization which supports orphans of AIDS and other vulnerable children. Money raised by Thembanathi goes toward feeding programs, a summer camp, childrens educational fees, and transportation for children to and from the preschool, among other needs. Larkans interest in the orphaned children of AIDS was intensified during her sophomore year at Wesleyan. She applied for the Davenport Study Grant, normally awarded to juniors doing thesis research, to go to South Africa and conduct research on the AIDS orphan crisis, and determine a strategy to best handle the dramatic increase of orphans expected by 2010. I wanted to work on something that was real and more relevant to today’s world, she says. Larkan received the grant, and for six weeks, she traveled around the city of KwaZulu-Natal, interviewing key players in orphan care and the AIDS pandemic. There, she worked with Reynolds, who received a similar grant her junior year to study in South Africa. That opportunity crystallized Reynolds’ interest in AIDS on an international level and expanded her interest to working with children orphaned and made vulnerable by HIV/AIDS.  Together, the women witnessed dozens of pre-school-aged children left alone to fend for themselves in areas where hunger, disease, and poverty were already part of daily life. They communicate with the children through an acquired toddler Zulu and hire a translator when conducting research. Together, the women witnessed dozens of pre-school-aged children left alone to fend for themselves in areas where hunger, disease, and poverty were already part of daily life. They communicate with the children through an acquired toddler Zulu and hire a translator when conducting research.

Our time there was fateful because we left with a desire, drive, and persistence to do more than just write about the AIDS situation, Larkan explains. We knew that we had to do something, no matter how small, to help the children that we had seen. Larkan, who spearheads Thembanathi’s fundraising efforts, has coordinated benefit concerts, bake sales, candy-grams, refreshment sales at athletic games and jewelry sales to raise money for the organization. Beaded AIDS pins, handmade by Zulu women, are the programs top seller. Thembanathi raised $14,000 in its first two years, and acquired a $33,000 grant from the Wellesley Rotarians and Rotary International to establish a water purification system at Holy Cross. Last summer, support from President Doug Bennet and the Christopher Brodigan Fund afforded the Thembanathi directors to return to South Africa for two months. While there, Larkan conducted some follow-up research on her thesis, which involved establishing a method of care for AIDS orphans using the school system. In addition, she developed a proposal that would link at-risk children in orphanages and schools with non-governmental agencies and social workers. Larkan and Reynolds are also building networks, and are trying to have their ideas discussed in academic public policy circles. Richard Elphick, professor of history, supervised Larkans thesis. I certainly encourage my students to do projects in public service, but Angela is doing extraordinary things on a number of different fronts, he says. Rather than studying AIDS prevention, Angela is working on the other end – how to deal with victims, or the tsunami of orphans. Shes very intellectually acute and practical, and its wonderful that shes out there raising money for her cause. A good part of running Thembanathi is administrative work, so Larkan and Reynolds can work using remote devices. Reynolds is living in Chad, Africa for 2 1/2 months doing more research as part of the completion of her Master’s in International Public Health from Johns Hopkins. Larkan, who finished her studies at Wesleyan in December, is living in Colorado. Some people don’t understand why I want to spend four hours a day working on something that doesn’t pay me, but they haven’t met the children I worked with, Larkan explains. They haven’t interviewed officials who sadly, slowly, tell you how they country is being ruined. It is the experience on the ground that keeps me going. Children are innocent and don’t deserve to be the victims of a crisis this large before they have even learned to read. Larkan and Reynolds hope to run Thembanathi full-time in the future and set up AIDS testing clinics and pediatric antiretrovirals for those AIDS orphans that are positive. Larkan credits her experience at Wesleyan with her present and future plans. Shes worked in the Office of Community Service where she ran a group called AIDS and Sexual Health Awareness, teaching HIV prevention in local high schools and raising awareness about local and global AIDS issues. Classes in government, economics, history and philosophy at Wesleyan provided Larkan with a broad range of pertinent information, allowing her to use to use these tools innovatively to build a model for orphan care. But it was Wesleyan’s students, she says, that inspired her to jump at the problem and try to change it. Wesleyan’s atmosphere is inspiring and makes you want to be active in creating change, she says. Most importantly, it makes you realize that you can be a part of that change. For more information on Themabanathi visit http://www.thembanathi.org/. |

| By Olivia Drake, Wesleyan Connection editor |