Now That’s Using Your Head: Student, Professor Collaborate on Brain Activity Study

|

|

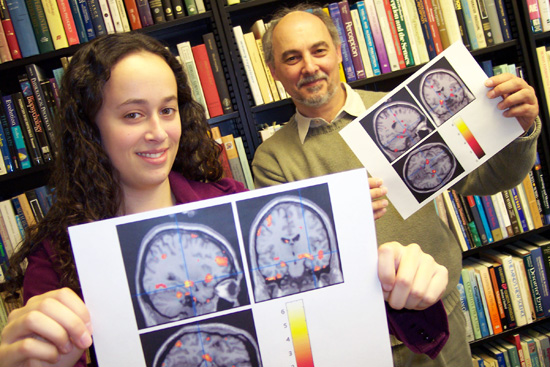

Rebecca Gordon 06 and her thesis advisor, John Seamon, professor of psychology, professor of neuroscience and behavior, pose with brain scans used in a recent study. |

| Posted 04/17/06 |

| For psychology major Rebecca Gordon 06, developing a research project idea was practically a no-brainer. Well, except for the fact that she had to study brains.

By examining functional magnetic resonance images, known as fMRIs, Rebecca Gordon 06 was able to see how the brain reacted on a cognitive and emotional level with healthy subjects and subjects diagnosed with schizophrenia. Her study The Mere Exposure Effect and Schizophrenia: An fMRI Study was completed April 11 after nine months of research. The mere exposure effect is a psychological way of saying people express likeness for things merely because they are familiar with them. “There have been no published fMRI studies of the mere exposure effect so I wanted to do a study that would contribute something new and important to several fields of psychology, says Gordon, who will graduate this year with a dual degree in psychology and music. Gordon, whose father is a clinical psychologist, coordinated her own research projects throughout high school including working with Parkinson Disease patients at a lab in New York. During her first year at Wesleyan, Gordon excelled in Psychology 101, taught by John Seamon, professor of psychology, professor of neuroscience and behavior. Knowing that his student already had research experience, Seamon suggested that she follow up on procedures he and other students conducted in the 1980s and 1990s on explicit and implicit memory. Explicit memory is a form of memory that involves conscious retrieval of past events; implicit memory is a nonconscious retrieval of past events. I encourage students who do well in my classes to get involved in research, either in my own lab or with others in psychology, and Rebecca was one of those special students, says Seamon, who became Gordons thesis advisor on the study. Gordon, who was working at the Olin Neuropsychiatry Research Center at the Institute of Living in Hartford last summer, had access to fMRI technology. Seamon suggested that she look for brain differences in explicit and implicit memory by measuring blood flow changes using the fMRI scanner. Since July 2005, Gordon has spent her summer, winter and spring breaks immersed in conducting research, as well two to three days a week during the school year. She continually sought research advice from Seamon and technical advice from Godfrey Pearlson, director of the Neuropsychiatry Research Center and professor of psychiatry at Yale University. By studying patients at the center in Hartford, she was able to perform two tests on 10 healthy control subjects and 10 schizophrenia patients. The subjects were placed inside the fMRI scanner during the study so she could monitor their brain activity. Using an assessment method called the recognition memory test to measure explicit memory, Gordon projected a series of novel objects, each for a few seconds. Subjects were then asked to answer the question: Is this a possible or impossible object? After viewing these novel objects several times and recording the decisions, Gordon collected her results. She then resented pairs of objects, one old and one new, and asked the subjects to select the object in each pair that they previously viewed. When she analyzed the neurological activity during this explicit recognition test, she found memory accuracy was correlated with activation of the hippocampus, the part of the brain used for new learning. In another test, called the affective preference test, Gordon measured implicit memory by asking the subjects which shape they preferred without asking them which one they remembered. During this test she found that there was still hippocampus activity along with a strong response from the amygdala, the almond-shaped neural structure in the brain that processes emotion. Gordon and Seamon were thrilled with the new discovery. This is a remarkable achievement for an undergraduate to go from a discussion with her advisor, take an idea and turn it into a tangible experiment that she then performed over a period of months, learn about this state of the art technology, collect and analyze data with technical help from the staff at the Institute of Living and produce new and interesting findings, Seamon says. Gordons report was submitted for partial fulfillment of the requirements for the bachelors of arts degree with departmental honors in psychology. She hopes to get her study published in a professional psychology journal. In addition, she will present her study during the Psychology Department Poster Session April 18. “I can’t believe that even as I got to the very end of my project, I never got tired of it. I was always excited about the idea of finding something completely new,” she says, holding two gray brain scans, speckled with colors. The colors illustrate where in the brain activity was happening during the subjects tasks. Gordon will return to the Institute of Living this summer for continued research, this time focusing on autistic children and people diagnosed with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Next fall, she will begin graduate school at Yeshiva University in New York where she plans to continue her studies in psychology. |

| By Olivia Drake, Wesleyan Connection editor |