Malamut ’12 Photographs Rare Eclipse for NASA

On July 11, Craig Malamut ’12 photographed a pacific solar eclipse 2,500 miles west of South America.

As a Keck Northeast Astronomy Consortium Summer Fellow, summer exchange student, Malamut had the opportunity to travel to Easter Island with a group from Williams College. The last time an eclipse occurred over the island was in 591 A.D.

The expedition was led by Jay Pasachoff, the Field Memorial Professor of Astronomy at Williams College and chair of the International Astronomical Union’s Working Group on Eclipses. This was Pasachoff’s 51st solar eclipse study; it was Malamut’s first.

“Before getting this position, I was thinking my first total solar eclipse would be the 2017 eclipse that runs across the entire United States from Oregon to South Carolina,” he says. “I never in a million years thought I’d be going to Easter Island to see the 2010 eclipse. It was one of the least viewed total solar eclipses in recent history due to the fact that most of the path of totality went over the Pacific Ocean.”

Before the eclipse, student researchers Malamut and Muzhou Lu set up seven cameras, five tripods, two tracking mounts, seven lenses, seven solar filters and four laptops running camera software.

“We had about nine, 50 pound boxes of expensive, complicated, heavy stuff. The kind of stuff you don’t want to transport to Easter Island,” Malamut recalls.

In order to operate their seven cameras at the same time, the group purchased special software that would automatically take pictures and change settings on the cameras. Malamut wrote the scripts with all the specific camera settings for each picture, and operated two of the cameras manually. By using a super precise GPS clock and scientific predictions, the group knew within one second when the eclipse would start.

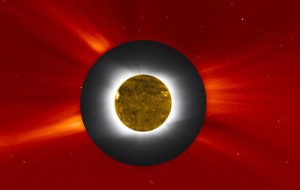

In a total solar eclipse, the moon blocks out the solar surface of the sun. The sun’s glowing photosphere is covered during the eclipse, and the corona, or the sun’s atmosphere, becomes visible. By the end of the eclipse, the group had taken about 4,000 high-resolution images in order to look for motions in the corona.

“In the past few years, the sunspot cycle has remained in an extreme low, but we now have evidence that the Sun is becoming more active,” Malamut noted from his study. “Hopefully, we will be able to see small changes in certain features of the corona in the short time interval between those images.”

The team provided one image of the eclipse to NASA. Steele Hill at the NASA Goddard Spaceflight Center combined the photo with one from the Naval Research Laboratory’s coronagraph on the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory and one from the Solar Dynamics Observatory to make a widely-distributed composite image.

With help from Miloslav Druckmüller of the Czech Republic, who uses extensive image processing to bring out fine details and high contrast in the images, the group plans to compare their images taken from Easter Island with images taken at different points along the path of totality including the Cook Islands, Tahiti and French Polynesia.

In addition to the Easter Island Eclipse study, Malamut, Pasachoff and Lu spent one week collaborating with astronomers at the University of Chile in Santiago, using one of their telescopes to see an occultation of a faint, 14-magnitude star by Pluto that was only visible from parts of South America and Africa. The team successfully saw a dip in brightness in the star for about 90 seconds, meaning Pluto passed in front of the star.

Malamut will co-author a paper on Pluto’s atmosphere, which will be important for the arrival of NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft at Pluto in 2015.

The summer consortium team was accompanied by a National Geographic Channel documentary crew.

“Since I’ve been little, I’ve always had an interest in astronomy. I was one of those kids who watched all the documentaries on outer space and read books on astronomy, so it was almost surreal actually being in one of the documentaries that I would have watched.”