Bissell ’05 Creates Art as Collaborative Healing

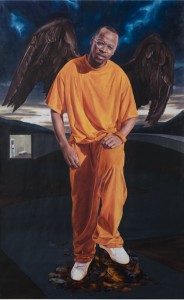

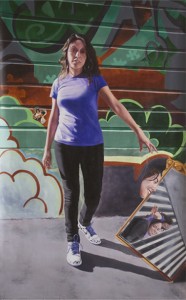

The eight portraits are larger-than-life, eight feet tall, of heroic proportions. Four of the subjects wear the baggy, bright orange garb of prisoners—which they are. The other four subjects are teens who have an incarcerated parent. In each painting, background icons—a hand grabbing the ankle, a daughter at the ocean, a zoo, family photographs from the past, a mask falling into a breaking mirror—depict the stories of these lives affected by the correctional system.

The oil and acrylic portraits were produced in what San Francisco artist and teacher Evan Bissell ’05 calls a “collaborative dialogue. They were on exhibit at SOMArts Cultural Center Main Gallery through Sept. 19, as part of his work, What Cannot Be Taken Away: Families and Prisons Project.

Along with the portraits, the exhibit included a labyrinth for a meditative experience in personal reflection on the nature of healing and forgiveness, a 36 foot timeline looking at the relationship of incarceration, labor and education in the U.S., and extensive documentation of the project process.

The exhibit and the portraits, says Bissell, evolved from his experience as a teacher and meditations on healing and community. The project was an attempt to create an educational space that focused on dialogue, creativity and healing as an alternative to punishment.

He explains the process behind the exhibit: “Beginning in November of 2009, I met weekly with two groups—youth whose fathers are or have been incarcerated, and fathers in the San Francisco County Jail. The participants were not related, but shared their experiences, their thoughts on forgiveness, stress, change and power,” writes artist Evan Bissell on his Web site.

“The work made and conversations had during the workshops moved organically based on what the group wanted to discuss and focus on,” he notes. “For example, the youth group chose to create the paintings of the eyes, and conversation topics developed based on ideas that some of the men put forth about ‘hurt people hurt people’.

“The actual paintings were collaborative in the sense that I worked closely with each participant to design the narrative structures, the symbols and the colors as well as the body language of each portrait that made up the composition.”

As an artist committed to collaborative projects who has done a number of such works, Bissell still finds the community process of making art to be powerful. What he learned from an anthropology class remains central to his work:

“Professor Gina Ulysse pushed me to think about how I would work with other people’s stories in a way that was not only ethical, but also empowering. This continues to be very important in my evolution as an artist. I go in to these projects prepared to be surprised,” he says. “Creating something together allows people to open up and talk, and to heal. Creativity is an affirmation of our humanity.”