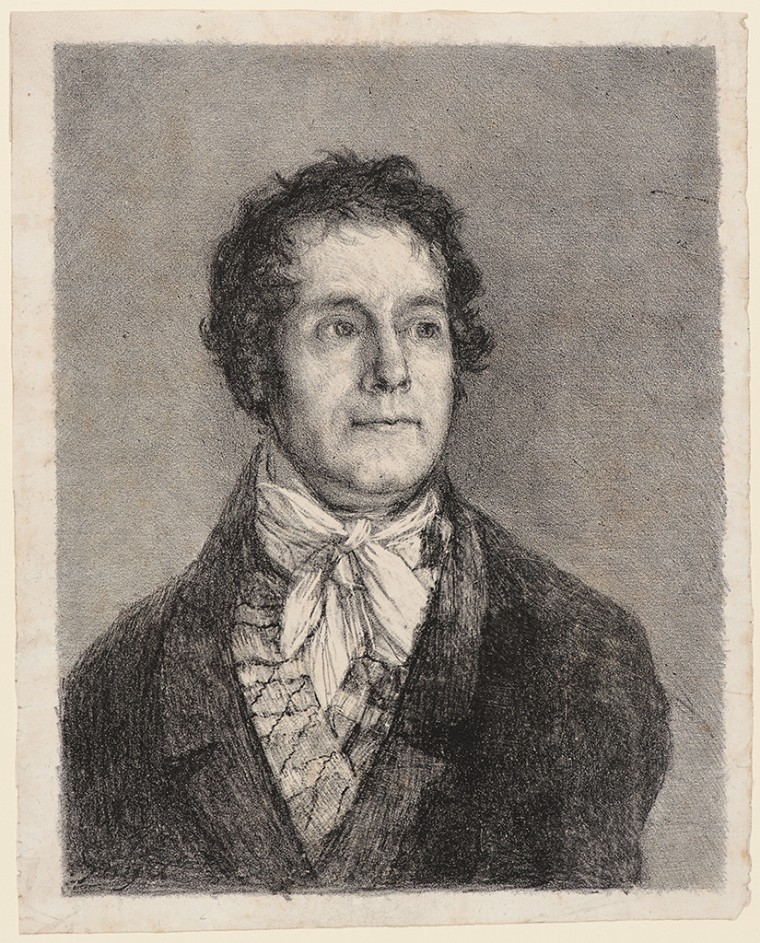

Davison Art Center’s 19th Century Goya Print Exhibited in Boston

One of Davison Art Center’s most important works – an early 19th century Francisco Goya lithograph – will be shown in a major art exhibit in Boston this fall.

The print, a portrait of the printer Cyprien-Charles-Marie Nicolas Gaulon, was made at the end of Goya’s life, between 1825 and 1826, and is one of only two known “first state” copies of the work (the other is in France’s Bibliotheque Nationale). Gaulon taught Goya lithography during the artist’s senescent exile in Bordeaux.

“It’s a portrait of a friend, the man who taught him this technique, towards the end of his life,” said Clare Rogan, curator of the DAC. “It’s a view onto Goya’s life at the time.”

The print was lent last month to the Museum of Fine Arts, where it will be exhibited in “Goya: Order and Disorder” Oct. 12-Jan. 19. The largest Goya exhibit in North America in 25 years, the show will include everything from the portraits of aristocrats that established his reputation to the prints and drawings that carried the Spanish artist’s fame beyond his country.

Goya is known as an Old Master, but also as one of the first modern painters and printmakers; while his early career was fed by portraiture of the Spain’s elite class, the political imagery of his later work led to his departure from Spain for France in his last years. Despite debilitating illness, Goya thrived in Bordeaux amongst like-minded artists. He used the new technique Gaulon taught him – lithography – to create some of his most famous works, a series of large bullfighting scenes known as the Bulls of Bordeaux.

The Wesleyan print’s importance goes beyond its subject matter. As a “first state,” it represents the initial version of the work (lithography allows for multiple changes with every reprint). “It’s a summation of Goya’s views,” Rogan said. “This is as close as we can get to what he was thinking when he made the print.”

How did such an amazing work land at Wesleyan? The cinema-worthy tale is as interesting as Goya’s last years. During the 1950s, the University Librarian, sorting through boxes of books in Olin Library’s attic – acquired in large lots and uncatalogued – asked Heinrich Schwarz, the Davison curator at the time, to come take a look at a 19th century album containing French prints. The curator sat in Olin, flipping through the largely uninteresting, although authentic, works. His reaction when he turned to what was most certainly a Goya, of high quality and unquestionable significance, went unrecorded.

Since then, the portrait of Gaulon has had a home and pride of place at DAC, which boasts more than 250 other works by Goya, as well.