Slobin’s Afghanistan Music Recordings, Field Notes Archived Online

Between 1967-1972, ethnomusicologist Mark Slobin was one of only four Western ethnomusicologists who managed to complete research in Afghanistan before the subsequent Soviet invasion, civil war, and anti-music Taliban regime.

During these five years, Slobin, who retired from Wesleyan 2016 as the Winslow-Kaplan Professor of Music, completed a comprehensive documentation of music, culture, language and society in the Afghan North. Given the region’s volatile unrest, no further musical—and by extension cultural—studies have been undertaken since.

Slobin’s rare survey of this time period is now available online through Alexander Street, a producer of online educational resources. “The Mark Slobin Fieldwork Archive, Music in the Afghan North, 1967-1972” draws on materials deposited at Wesleyan’s World Music Archives, directed by Alec McLane. McLane brought Slobin’s work to the attention of Alexander Street. The site packages all of Slobin’s materials: the sound files of folk music recordings, films, hundreds of images and field notes.

Slobin’s project is part of Alexander Street’s Ethnographic Sound Archives Online, which brings together 2,000 hours of audio recordings from field expeditions around the world, particularly from the 1960s through the 1980s—the dawn of ethnomusicology as a academically accepted discipline. The archives are available for subscription by university libraries worldwide.

Slobin writes, “I had meant my fieldwork to be in villages, but the government did not allow it, and there were no conditions to stay in a village, even overnight. So, I worked in a variety of towns of differing size and importance in the North’s three regions.”

Slobin later divided his project into segments based on locations, including The Radio Afghanistan Series; The Faizabād Tapes; The Aqcha Series; The Tashqurghān Series; The Samangān Series; The Andkhoi Series; The Bābā Qerān Series; The Herat Series; The Baghlan Series; and The Saripul and Qizilayāq Series.

Aqcha, in particular, was a crucial location for his research, collection and understanding of the general patterns of music in the North. “It presented the model for the local market town, a magnet for country folk—farmers and nomads—twice a week for the market days,” Slobin describes. “This made it a point of intersection for ethnic groups and also a possible site for public music-making on a regular basis, as opposed to the private celebrations or occasional festivals that occasioned performance.”

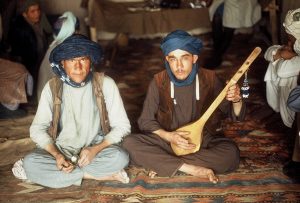

One of Slobin’s biggest challenges was finding musicians that he could record privately. A key musician was Aq Pishak, “the white cat,” a moniker for refugee Turkmen who added animal sounds to his repertoire of regional dance tunes from the Uzbek and Tajik traditions. Pishak, who is included in the documentation, played on those group’s favorite instrument, the dambura. A survey of the Aqcha bazaar can be found in the film footage section of this project, ending with a shot of Pishak and two Uzbek singers in a teahouse.

Eventually, Slobin won a graduate student prize of the Society for Ethnomusicology for his paper on Afghanistan town-types and musical life. This soon helped Slobin gain his first and permanent appointment at Wesleyan in 1971.

Slobin also is an expert on East European Jewish music and klezmer music. He has been president of the Society for Ethnomusicology, president of the Society for Asian Music and editor of Asian Music. He has been the recipient of numerous prizes, including the Seeger Prize of the Society for Ethnomusicology, the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award, the Jewish Cultural Achievement Award (for lifetime achievement) from the Foundation for Jewish Culture, and the Curt Leviant Award In Yiddish Studies from the Modern Languages Association (honorable mention). He was a finalist for the National Jewish Book Award for Chosen Voices (1989). In October, Slobin will be inducted to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Other examples of Slobin’s field notes and publication materials are online here.