Sunderland ’92 and Kaplan ’20 Discuss Education

As spring semester approached, Avery Kaplan ’20 gave her former Bedford [Mass.] High School history teacher, James Sunderland ’92, a call to talk about what education means in 2020. Below is an edited portion of their conversation.

Avery Kaplan: What do you think Wesleyan aspires to be, and what do you think education in this country aspires to be?

James Sunderland: It’s always seemed to me that Wesleyan is a place that sincerely wants to be engaged in learning; making an impact in the world in a way that’s also humble, listening to people with an open mind, the free exchange of ideas, disagreeing without being disagreeable. And that we’re all in this shared effort to make more sense of the world. The underlying idea is authenticity; an intent at no pretense.

AK: It’s interesting, that idea of authenticity. One of the worst things you can be labeled as at Wesleyan is “performative”—it’s a pejorative term. How do you think Wesleyan fosters authenticity?

JS: There’s certainly an explicit message of it at Wesleyan, but it’s something that is much easier said than done. For one thing, the professors I had were sincerely engaged in their work. Engaging with students as equals is important. At Wesleyan, I felt that my voice was respected by my professors, that they weren’t pedantic. I think that in general Wesleyan attracts a student body who wants to go someplace where you can have interesting conversations with peers. My friend group, for example, was pretty diverse in terms of interests. We weren’t all the same majors, we met by the randomness of first-year dorms, and it’s made for some really cool conversations over the last 30 years.

AK: I can definitely see how your time at Wes influenced the classroom culture you cultivate at the high school. It was also clear, when I was your student, that you were actively teaching us to become citizens. How has your strategy to teach civics and create citizens changed as you’ve been teaching?

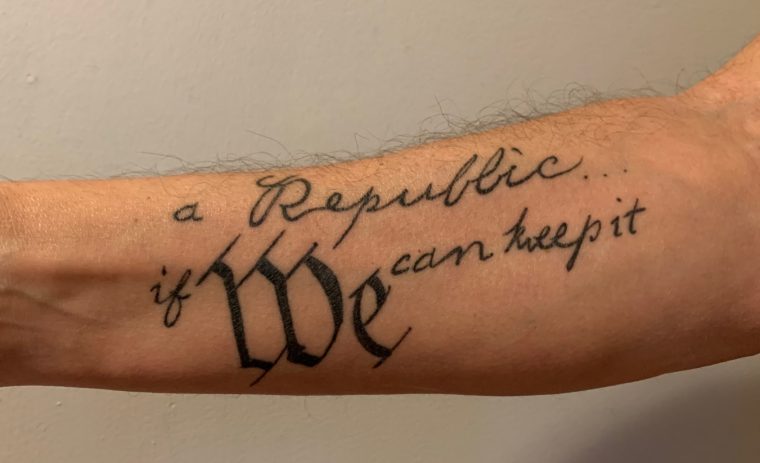

JS: I think it’s gotten more explicit. I don’t know if you remember the course goals that we had, but now we’ve synthesized them into the one main goal of “Keep the Republic.” What we’re doing here is trying to prepare people to be contributing members of society for the benefit of all, not just for the benefit of oneself.

Frankly, with the political environment the way it is, there’s a lot more engagement from students in general, and it feels like students find connections more easily now. Today, with freshmen, we were looking at one paragraph from Washington’s farewell address that speaks to partisanship and how it opens the door to foreign influence. It was like, “Man, did he write this today?”

The biggest difference is students are definitely chomping at the bit to vote, in ways that I don’t remember in the past. Like current juniors, they’re going to miss out on 2020, and they’re really bummed out. As a history teacher, and as somebody who’s interested in civics, it makes me happy that people care about citizenship.

JS: I think in America, education is supposed to be a dynamic force. I’m not saying we necessarily accomplish that, but I see myself as a part of an institution with a long-established purpose to create an opportunity to help people be more free. A big reason why I’m involved in education, as opposed to another form of civil service, is I do think that education has a particularly profound role in mixing things up.