Faculty Share Insights on Teaching during a Pandemic

When the COVID-19 outbreak disrupted in-person classes last spring, several faculty found innovative and creative ways to adapt to online teaching and learning.

In the first of a fall-semester series, we’ll be highlighting ways faculty from various departments are coping with teaching during a pandemic, and showcase individual ways courses are thriving in an online or hybridized environment.

In this issue, we spotlight Naho Maruta from the College of East Asian Studies; Alison O’Neil from the Chemistry Department; and Ron Jenkins from the Theater Department.

Naho Maruta, associate professor of the practice in East Asian studies, chose to teach her fall 2020 classes entirely online because several students in her Japanese language classes are international students who were not able to make it back to campus this fall due to travel restrictions. Even her foreign language teaching assistant is working remotely from Japan.

“It’s important we’re live and synchronous because we have lots of conversation activities,” Maruta said. “Luckily, all students in my class are either in the Eastern Standard time zone or in Asia time zone, so having an 8:50 a.m. class works for both sides, even synchronously.”

During a regular semester, Maruta would create “language partners” by pairing students in upper-level Japanese courses with Wesleyan students from Japan, but with most native Japanese students off-campus, she began a new collaboration with Doshisha University in Kyoto, Japan.

“We’ll have their Japanese undergrad students matched with my Japanese language students. They’ll meet online once a week for conversation practice. This is the first-time-ever trial and I’m excited,” she said.

Maruta says the “silver lining” of teaching a language class online is the unexpected, and often humorous “Zoom bombs” that occur in the students’ homes. A dog or cat passing behind the student, for example, lead to “moments that give us good laughs” and “even let us naturally start conversations related to these in Japanese.”

“So far, [teaching a language class online] has been working pretty well, though I still can’t wait to go back to the classroom to teach,” Maruta said.

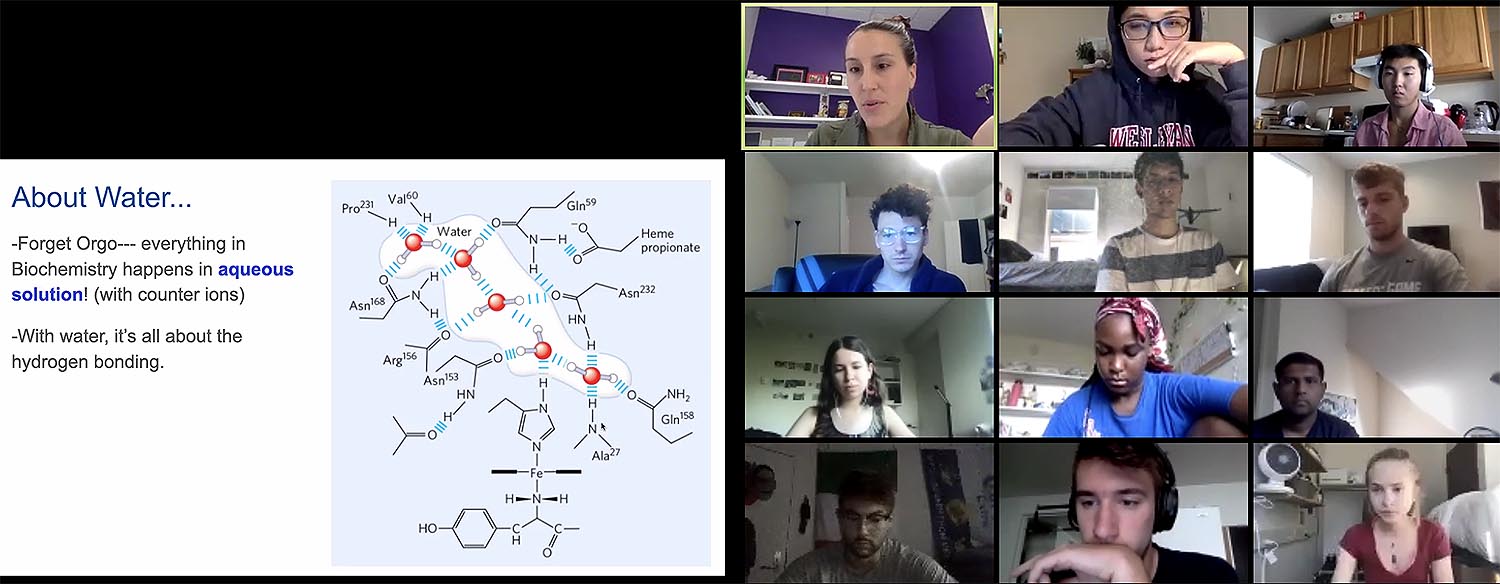

This fall, Alison O’Neil, assistant professor of chemistry, is teaching CHEM 383: Biochemistry entirely online to 75 students.

“I thought that 50-minute synchronous lectures, three days a week, via Zoom would be tedious for the students and wouldn’t promote community—something that has been highlighted as essential for a successful online class,” O’Neil said. “So I chose to ‘flip the class.'”

O’Neil pre-recorded her lectures that students can watch on their own time, and during class, she breaks the class into groups of three where they work together, over Zoom, on a problem set that integrates concepts from the lectures and reading.

“By assigning random groups every class, and providing an ‘ice breaker question,’ I’m hoping students will all get to meet each other and this will foster community,” she said.

In lieu of a cumulative final exam, each student will choose a final project to highlight their mastery of a biochemical concept.

“For example, they can create a recorded lesson that can be used next year, give a 20-minute seminar about a recent publication highlighting the biochemical concepts to staff, or read an assigned research article and write a reflection and answer a series of questions,” O’Neil said.

Ron Jenkins, chair and professor of theater, who has taught THEA 115: America in Prison: Theater Behind Bars since 2014, would normally take his students to a local correctional facility where they’d work and learn alongside incarcerated individuals on reimagining Dante’s Divine Comedy as a team. Together, the Wesleyan students and their incarcerated partners would collaborate on a performance that highlights the contemporary relevance of the medieval poem through a script that is a mash-up of street slang, rap narratives, sacred music, and first-person accounts written by the incarcerated students interwoven with fragments of Inferno, Purgatory, and Paradise.

But due to the pandemic, Wesleyan students aren’t allowed to visit the prisons.

“I am changing the focus of the class to work with formerly incarcerated individuals and their family members who have access to Zoom (incarcerated individuals do not). Although this is in some respects disappointing, I am learning that there are surprising advantages to the new format,” Jenkins said.

Jenkins says the online format allows for family members of incarcerated men and women, who are rarely included in the current public discourse on prison reform, to share their points of view. Although they’re not allowed into the prison to participate in the class with their incarcerated loved ones, they are able to talk to the class over Zoom.

Jenkins also teaches a similar class, Performance Behind Bars, at Yale Divinity School, where he has already begun the new incarnation of the course this fall.

“Stories gleaned from our collaboration with formerly incarcerated individuals and their families reinforce what we have already learned from incarcerated students about the role of the criminal justice system as the heart of racial injustice in America,” Jenkins said.

The Wesleyan version of the course will be offered in the spring.