Exploring Sustainability, Building Community, and Fostering Connections: Frances Ostensen ’24 and Her SEA Semester

When Frances Ostensen ’24 set sail aboard the SSV Robert C. Seamans this fall, she knew she was in for an adventure.

Ostensen, a biology and Science in Society Program double major who spent the semester abroad with the Sea Education Association (SEA), learned more about the environment, human civilizations, and their endless connections than she ever expected.

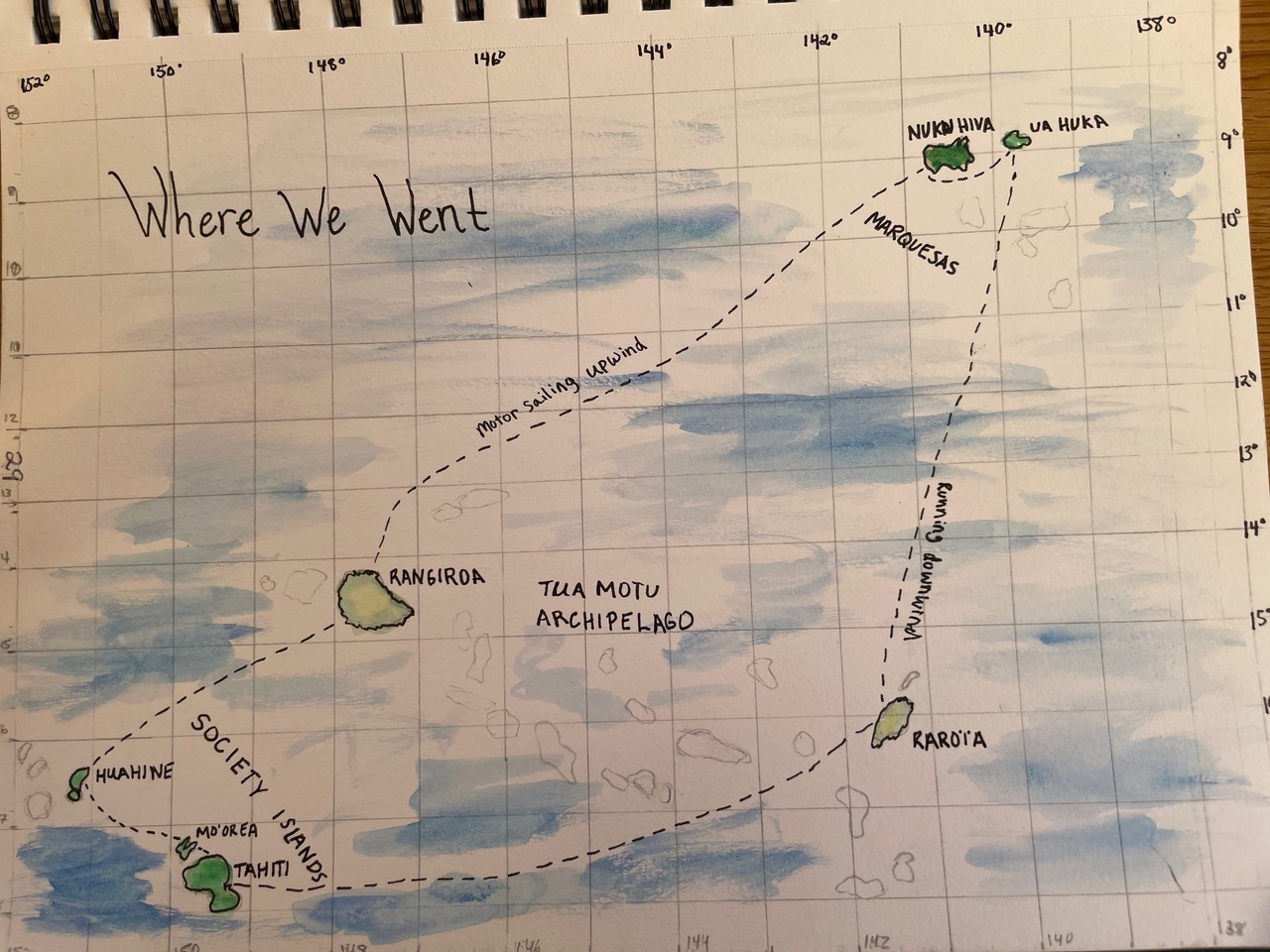

Her chosen program, called Sustainability in Pacific Island Communities and Ecosystems, began in Woods Hole, Mass. in October. After flying to the South Pacific in November, Ostensen set sail in a loop around Polynesia alongside seven other students, professors, and crew members on a 134-foot brigantine. The group visited the islands of Tahiti, Mo’orea, Huahine, Rangiroa, Nuka Hiva, Ua Huka, and Raroïa.

The program stood out to Ostensen because of its relevance to her fields of study and her desire to learn in an environment which questions Western perspectives and incorporates broader viewpoints. She participated in a SEA summer program in high school and loved it, so she wanted to explore the ocean for a longer period of time during her semester abroad.

Both on land and at sea, the group delved into themes of sustainability, colonization, and connectivity through their classroom lessons and hands-on experiences.

“We did a lot about food because it is a really big way people connect to their environments,” Ostensen explained. “We learned about the impact of colonization on food and food waste and how, even 100 years ago, there were no stores on any of these islands. People were subsistence farming or fishing in the reef. We learned about how, with the impact of colonialism, a majority of food is imported. The islands could support all of these people, but because of colonization and forced erasure of cultural identity, now they’re importing all their food.”

Ostensen recalls a conversation she had with a Tavena, a local leader, on the island of Huahine. The interaction stuck with her because of how effectively he summed up environmentalism and the need for indigenous food sovereignty.

“[Tavena Coro] said if we live today the way our ancestors did, we wouldn’t have to ask all these questions about climate change,” Ostensen said. “He was telling us about traditional forms of managing reef ecosystems. There’s this whole traditional thing of not fishing in the reef at certain times of the year, and when they started implementing that again, the reef rebounded and now they’re getting way more fish than they were in the past.”

This traditional system of reef management, called a Rahui, relates to the Tahitian word for “respect.” Ostensen felt inspired by the respect and reciprocity Tavena Caro described his people showing their environment.

She also explored the relationship between food and the environment aboard the boat, which often had a net trailing behind it so the students could study the plankton they caught.

“From a biological perspective, I learned a lot about food chains,” Ostensen said. “You’ll be in the middle of the ocean, and it just looks like there’s nothing, but then you look in the net and it’s all this biodiversity. It’s really cool to see the different elements of the food chain. You’ll sometimes see flocks of birds, and you’re like, ‘Oh, my God, I guess there’s a bunch of fish over there.’ I feel like I grew connected to a web of life.”

One of Ostensen’s professors, ethnohistorian and native of Polynesia Josiane DiGiorgio, took Ostensen under her wing. DiGiorgio brought biology and culture together for Ostensen, even showing her how to scale a parrotfish, which holds cultural significance in Polynesia.

Ostensen also expressed how transformative it was to be able to travel to places by boat that she would have never gotten to visit otherwise.

“Since we were sailing, we went to a lot of places that are not on TripAdvisor,” Ostensen explained. “We went to an island that had 50 people living on it, very off the beaten path places to go to see a different form of life and really dive into a culture and be humbled and transformed by that experience.”

She said one of her favorite parts of the program was connecting with locals to learn about their experiences living on the islands.

“On each of the islands that we went to, we were constantly learning because we were in a new place and taking in new information and [making] different connections, and we talked to different people on the islands,” Ostensen said. “That was a different form of learning.”

These island experiences taught her a lot about community, care, and connection, Ostensen said.

“People are so welcoming,” Ostensen said. “Everywhere we went, people were so happy to see us and really wanted to teach; it just made me feel really welcomed and happy.”

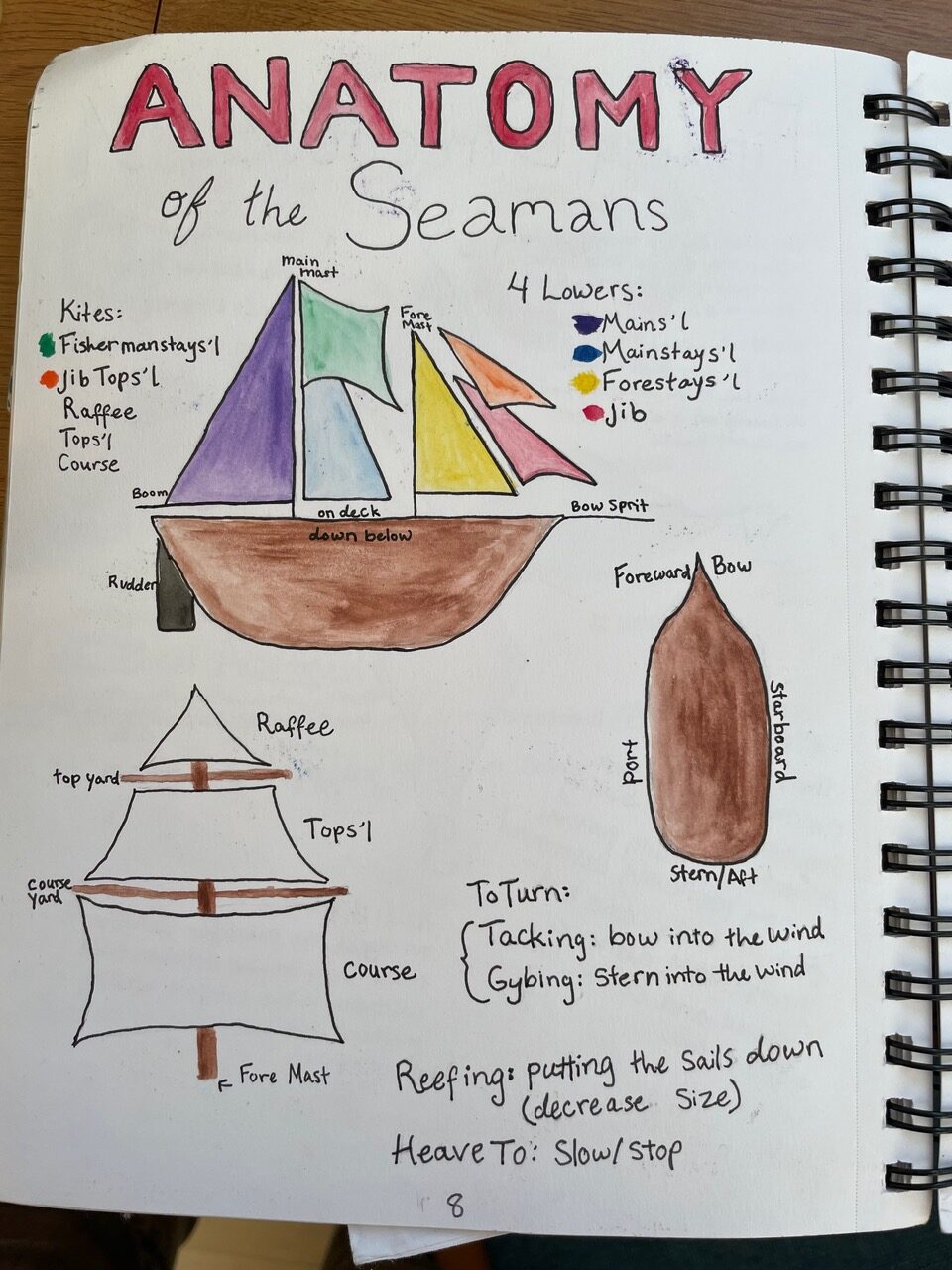

She found another source of community in life on the boat itself. Ostensen built relationships with her classmates through shared activities and diving into her classes. When she wasn’t studying plankton samples, she was snorkeling near various reefs, learning celestial navigation, and splitting watch times with her cohort.

“I think you can learn a lot from just being outside of your environment, in a new environment,” Ostensen said. “I felt like I really made the most of every single day, which was nice.”

Still reveling in the magic of her semester at sea, Ostensen sees herself pursuing a future in outdoor education as a means of combining her love of nature and the environment with her desire to teach children about the planet. She mentioned how on the island of Ua Huka, the elementary school curriculum included children taking care of the reef.

“This was a really incredible example of decolonization and getting children to connect with their ancestors and identity through environmental stewardship,” Ostensen said.

Ostensen hopes to make an impact through hands-on work nurturing the planet in the future.

“Research is very important, but I don’t think the reason why I care about the environment is because I’ve read a scientific paper that proves that the trees are dying,” Ostensen said. “I think bringing kids out into the wilderness and getting them to have awe and wonder and experience how beautiful the world is and be humbled by that is the path towards a better world. I think my experiences in the natural world are the reason why I care so much about the Earth.”