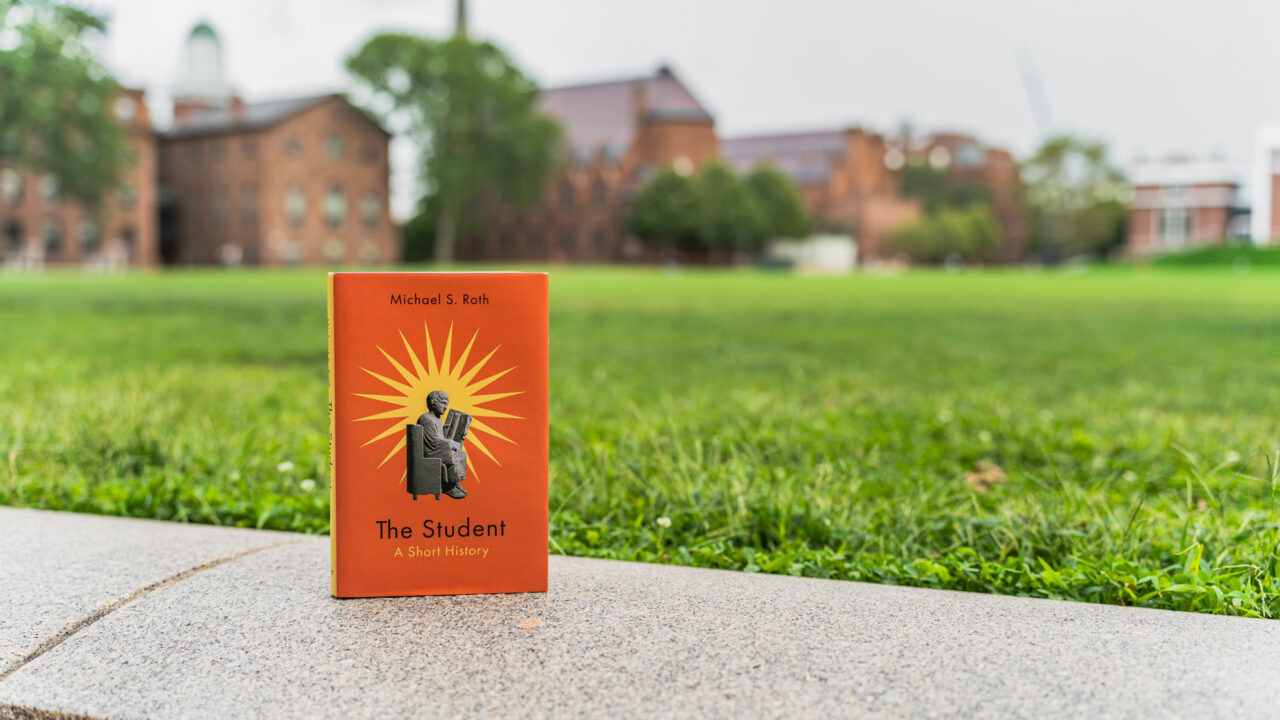

Finding Freedom Through Learning, President Roth Explores the History of Being a Student

As a historian, author, and lifelong teacher, Michael S. Roth ’78, President of Wesleyan University, has dedicated much of his career to understanding how people make sense of the past, so when he was approached by his editor at Yale University Press to consider what it meant to be a student, he decided to start at the beginning—the very beginning.

Beginning with the followers of Confucius, Socrates, and Jesus and moving to medieval apprentices, students at Enlightenment centers of learning, and learners enrolled in twenty-first-century universities, in his newest book, The Student: A Short History, President Roth explores how students have been followers, interlocutors, disciples, rebels, and children trying to become adults. He hopes the book’s readers will see that “learning is a form of freedom and that we should protect our access to learning in our own lives, and the lives of our families, and fellow citizens.”

I spoke with President Roth shortly before the publication of The Student, just as Wesleyan’s fall semester was about to begin in the wake of a summer filled with national debate about access to higher education as well as how the rise of artificial intelligence threatens learning. The following is an edited excerpt from our conversation.

When you set out to write The Student five years ago, was there any sense that our country would be reckoning with big questions around what it means to be a student and who should have access to education like it is right now?

The idea of the student is a screen on which we project a lot of our anxieties about other things. What does it mean to grow up? What does it mean to be independent? What does it mean to be free? What does it mean to have social mobility and to be able to change the conditions of one’s life? A lot of those pressures get worried over through thinking about schools and students. They’re a liminal group, so whatever the issue is, students can play an outsized role in how we work through that issue. And so it’s not a surprise to me, except the AI part. When I was writing the book, I hadn’t been thinking about generative AI.

People who are willing to turn their thinking over to machines destroys the idea of being a student. But when I wrote the book, I was thinking more generally about independence and freedom, those issues now pushed to an extreme because of the option of having a machine do all your thinking for you and not just your research.

Was education always a path towards freedom for students?

Through most of Western history, the vast majority of people were not expected to get schooling of any kind, let alone higher education. However, the tension in higher education between the vocational or the economic and the broader meaning of life issues that education is supposed to illuminate has been there ever since higher education became available to lots of people. And so throughout the 20th century in the United States, there were immigrant groups that saw higher education as a vehicle of social mobility. Whereas many of the folks who went to places like Wesleyan or the Ivy League schools before the Second World War, were solidifying their social position, not striving for social mobility. College was for many more like a finishing school.

That really changed when immigrant groups, especially Jews, started going to colleges in higher numbers. Social mobility was top of mind for immigrant groups and for many returning GIs. In response, you get all these efforts to filter, to curate a class…the whole idea of holistic admissions was created to keep those marginalized groups out.

For several decades now, colleges and universities have really tried to offer not only ways of getting ahead economically, but also ways to give people the opportunity to learn to think, and to learn to learn, and express themselves. Of course, this can help economically, but it can also help one lead a more capacious life—to help one flourish in one’s life.

Did your family expect that you would go to college?

My parents didn’t go to college, but they really did think that their kids should. It was that American dream. They did not have really any idea what college was like, but going to college was an expectation.

I started looking at highly selective schools because I became bookish as a high school student. I wanted to be a writer and I wanted to hang out with writers, and artists, and musicians. And all that was all right in front of you at Wesleyan in the 1970s.

You write in the book, “The question of when exactly students are supposed to think for themselves doesn’t have a clear answer.” I’m curious what you mean by that, especially in the context of a school like Wesleyan, where we often discuss faculty and students working and learning together.

While you’re on campus, there are a lot of students who imitate their teachers, whether it’s through gestures, ideologically, or aesthetically. Sometimes it’s by being critical because teachers sometimes reward that. But when you start thinking for yourself, you can also recognize that you’re using tools that you got from your teachers. It’s a little bit like, when do you stop being your parent’s child? Never. But when do you stop being a child? Well, at some point you’re not just a child, you’re also an adult, and you’ve got that debt, or connection, or both.

Now that you have charted the history of being a student, what do you imagine is the next evolutionary moment of learning and teaching?

I think AI is interesting in this regard. I’m still wrestling with it myself because I know I will tell my students next week, “You don’t want to let a machine think for you.” And I told this to a friend of mine, he laughed at me. He said, “Of course they do when there’s a deadline.” And I get that. I mean, there are these deadlines, and pressure, and you want to do something else. Some people may not want to think. And so I think the sophistication of the technology matters a great deal. I’m trying to think through the analogy with technologies that have helped people do, say, computation, so they don’t have to learn how to do computation anymore. I’m in the worrying stage. The challenge is that AI makes things very easy, or easier, but part of learning is to overcoming difficulty. And if you don’t overcome the difficulty, you won’t learn.

I know that they can ask a bot now, “What did Rousseau say about inequality?” And they’ll get a decent answer, but they will have deprived themselves of the pleasure, and the challenge, and the difficulty of wrestling with the text. And I think that that is enormous loss if we allow that to happen.

Following the Supreme Court’s ruling that ended affirmative action, do you see the threat to access to education getting worse before it gets better? What can a school like Wesleyan do to ensure it remains committed to its values of accessibility?

So much will depend on the political choices that are made in this country in the next couple of years. I think that it’s entirely possible that our education system, not places like Wesleyan, but our K–12 system in public education will be starved by forces that don’t want citizens to learn or are comfortable with the vast inequality of learning that we have now. But it’s also possible that we’ll make political choices that will support teachers and students, universal pre-K, access to quality K–12 education, and stronger public education. All these things are within reach. We need a universal healthcare, and we need a universal respect for education. But whether we’ll get them in the next decade, that depends on the political choices we make in the next two years.

The Student: A Short History will be published September 12.