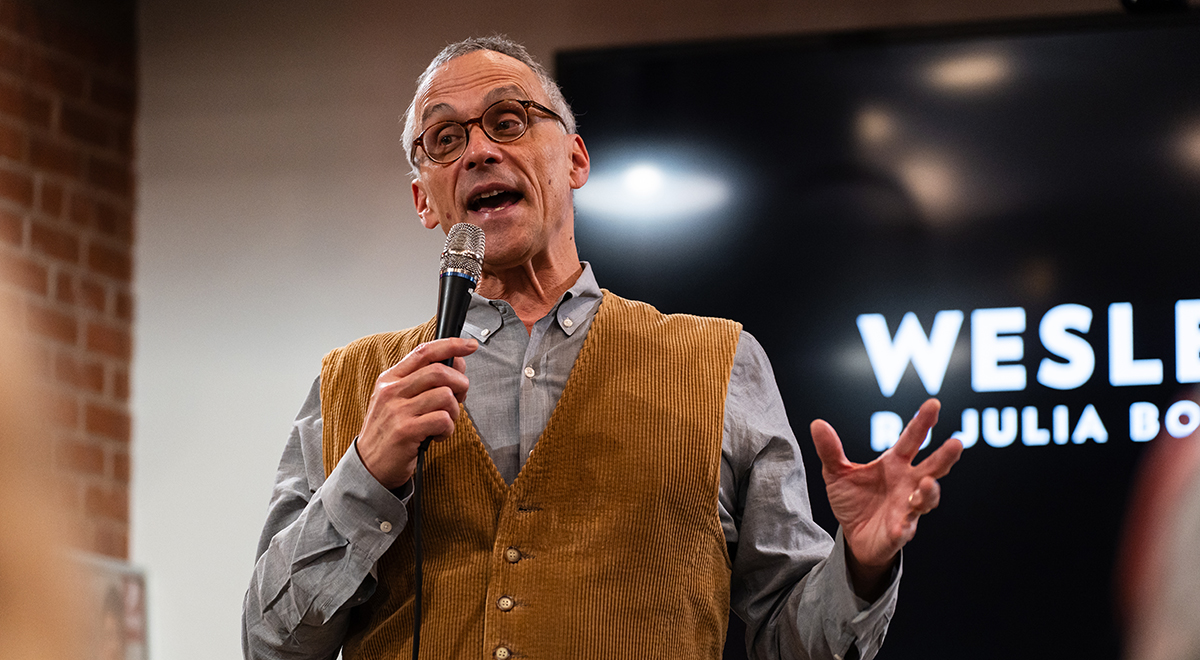

Roth on The Student, Pursuing Freedom Through Education at RJ Julia

A student can be more than critical. A student can learn to follow, think independently, be creative, or love—or, all three. The act of being a student, as President Michael S. Roth ’78 explores in his, is one of pursuing freedom.

“It’s so great to be a student, because you’re practicing freedom in a way that will increase your capacity to think for yourself and live with other people in a way that’s meaningful,” Roth said during a Feb. 1 talk with an attentive audience of students, scholars, alumni, and parents at RJ Julia Bookstore on Main Street in Middletown.

The Student: A Short History, his recently published book, narrates the dynamic history of the student over time and across platforms. Roth began the book with an exploration of the followers of three notable teachers—Confucius, Socrates, and Jesus—before overviewing the medieval apprentice, Enlightenment learning centers, and 21st century universities.

“Students are so impressionable because they’re younger and I think that you have to practice your freedom when you’re young,” Xee Xhang ’20 said after the talk. “How to navigate that as a professor or as a parent, it can be very complicated and so multifaceted. It just relates to so many different things like politics, culture, even history.”

Roth cited several examples in which people have used learning to free themselves of life circumstances. Benjamin Franklin wrote letters under pseudonyms that eventually led to his rise to prominence, freeing him from an apprenticeship under his brother that he did not want, as Roth highlighted in his talk. In Germany in the 19th century, students learned in a way that built character, developed morals, and learned to become, Roth said.

“You become free to participate in the community of which you are a part, you become a citizen through education,” Roth said. This philosophy spread throughout Europe in the 19th century before being adopted by American universities later, he said.

He also pointed to the expansion of access to secondary education for women in the 1900s. Women quickly became sizable portions of university classes and often took their education more seriously than men of the time, Roth said.

“It was just interesting to put myself in their shoes and go back in time to a period where you see men have these opportunities and not take advantage of them,” Xhang said.

The focus for many students shifted away from the classroom in the 1960s and 1970s to protest movements outside of campus. The Civil Rights Movement and anti-Vietnam War movement created swaths of political spirit at universities across the country, Roth said. “In the 1960s, in America and in Western Europe as well, the campus becomes a place where politics happens,” Roth said.

Wesleyan parent Glenn Meyers, father of Waverly Meyers ’26, said Roth’s remarks on how overly critical thinking can make someone lose the ability to love or appreciate material made him reconsider his own thoughts on critical thinking.

Moataz Derdira, Fulbright fellow from Libya, was also struck by Roth’s ideas of criticism, saying “sometimes I can be more critical than I should, so maybe that’s a wasted opportunity, maybe I should let go sometimes.”

Whether it is through criticism, following or rebelling against a teacher, or love of a subject, being a student means pursuing freedom. This is demonstrated throughout history and modern times, as Roth reflects in his book.

“The good life is being a student always,” said Roxanne J. Coady, owner and operator of RJ Julia Booksellers.