Birney Studies Ancient Perfume “Knock-Offs” in Athens as New Directions Fellow

There was something about Kate Birney’s research that smelled a little off.

As far back as the 4th century B.C., Greece was a global leader in producing a plethora of posh perfumes sold in handcrafted ceramic bottles marked with three chalky-white stripes.

“Much like today, some of these ceramic perfume bottles were ‘branded‘—made in distinctive shapes, and painted or decorated in distinctive ways—probably to tell the consumer what scent they contained, or which perfume house/region they were imported from,” said Birney, associate professor of classical studies and chair of Wesleyan’s Archaeology Program.

So when similar bottles, or unguentaria, were excavated from the site of Ashkelon in southern Israel, scientists assumed the Hellenistic-period (4th–1st century B.C.) perfumes were imported via trade routes. Or were they?

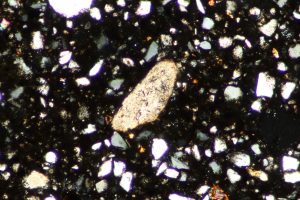

Through a Mellon Foundation New Directions Fellowship, Birney spent this past winter and early spring at the Wiener Lab of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, studying the ceramic petrography of bottles collected from Ashkelon. There, she worked with petrographic specialists and accessed the lab’s comparative collections.

“With ceramic petrography, we’re able to study the geological ‘fingerprint’ of the clay from ceramics, which can reveal where these bottles were produced,” Birney explained.

After analyzing the mineralogical composition of the unguentaria, Birney discovered the Ashkelon relics were not made up of Greek clay, but rather minerals from local lands.

“The petrography shows that the geological fingerprint is not from Greece,” she said. “This is still preliminary work, but it looks like workshops in Syria and Israel were knocking these perfumes off at a surprisingly high level of quality! They’re even decorated in the same manner, so that they would be hard to distinguish from the original.”

Although Birney’s research in Greece was cut short due to the COVID-19 pandemic, she plans to continue similar work by analyzing organic residues of these perfumes to try to reconstruct their contents.

“Hopefully we can figure out what kind of perfume these bottles contained,” she said.