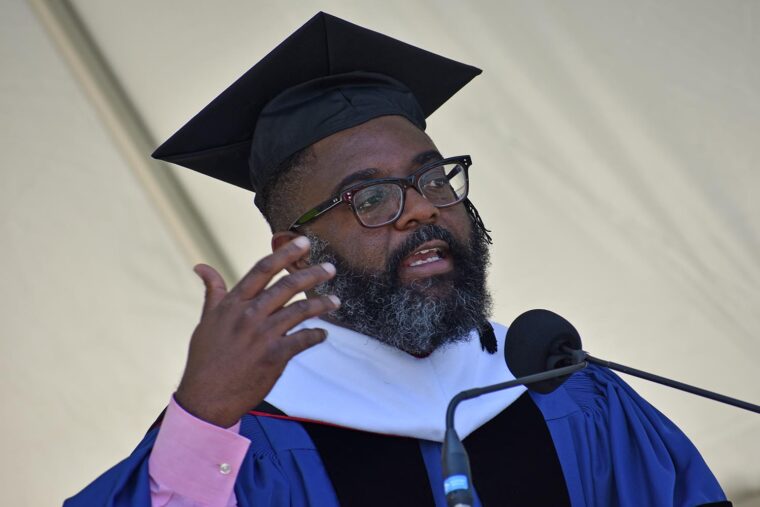

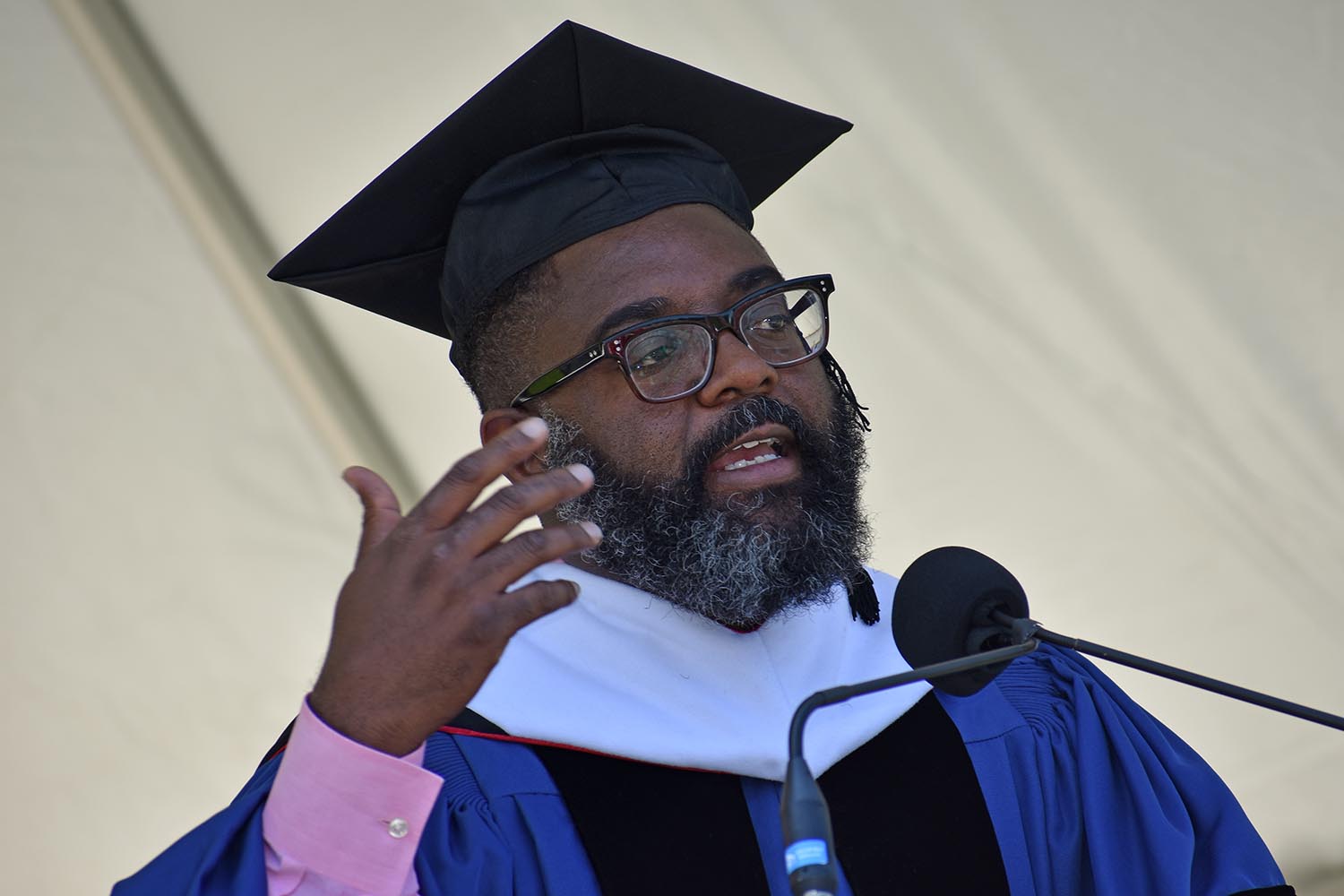

Betts Reflects on Time, “What We Owe Each Other” in 2021 Commencement Address

Award-winning poet, memoirist, scholar, and social justice advocate Reginald Dwayne Betts delivered the 2021 Commencement Address during Wesleyan’s 189th Commencement Ceremony on May 26.

In a powerful speech tinged with moments of humor, Betts focused on the theme of time and understanding our duty as part of an expansive community that includes lesser-seen members outside the traditional campus. Reflecting on how “these [COVID-19] pandemic days have turned time different,” Betts drew parallels to his own past history and that of other currently or previously incarcerated individuals, including eight students from Wesleyan’s Center for Prison Education program, who were among those earning bachelor of liberal studies degrees this year. He referenced the pandemic’s isolating effect on the graduates’ final year at Wesleyan and acknowledged the work they had done “of believing that education matters enough to keep doing it even as the world is falling apart,” and reassuring them that “this is just a start to figuring out what you’re meant to do in the world, but what a glorious start it is.”

As a 16-year-old, Betts was sentenced to nine years in a maximum security prison, during which time he studied literature and poetry, laying the groundwork for a career path that would include a BA, an MFA, a JD, and soon a PhD, as well as a National Magazine Award–winning essay in The New York Times Magazine, a Radcliffe Fellowship, a Guggenheim Fellowship, NEA Fellowships, and years of work in public defense, advocacy, and public service. He is also the founder and director of The Million Book Project, which “harnesses the power of literature to counter what prison does to the spirit.” During the ceremony, Betts was awarded an honorary doctor of letters degree from Wesleyan.

Betts’s remarks are below:

Thank you to the Board of Trustees and President Roth. This is a true and rare honor and I am grateful.

I also want to thank two of my friends who are professors here: Professors John Murillo and Lori Gruen. They have read literally everything I have written when it was in draft form. If you don’t have someone reading everything that you write, find that person in this crowd.

This graduation is different. And I know what I’m going to say but, I’m shocked that I’m actually able to say it. So first I’ll just say congratulations to everybody here in the audience today. I was told that there’s two or three things I need to do to make this a successful speech. The first was to tell a joke: They lost everybody’s diploma and you have to come back for one more year.

The second was to say something that was honest. And I’ll tell you that for years I’ve obsessed over time. I’ve obsessed over automatic watches. And I imagine that they tell me about time. Did you know that automatic watches are self-winding? Turn the back and look at one and you’ll get a glimpse of the gears. You get to see the inner beauty. Sometimes I wish that we were built that way. That it was a way for others to see our inner beauty when we walked through the world.

You know with an automatic watch, the second hand, they’re all different. It’s idiosyncratic. So what happens is from day to day you lose seconds. You’ve got to go and check the watch and make sure you don’t lose too much time. I feel like we move that way, especially over this past year. Burdened by obligations. Wanting to find time to be alone. It was far too easy to lose time. Far too easy to forget that life wasn’t just the accumulation of successes. It was also sadness. It was also frustration. And it was also dancing. And finding all the ways to reckon with the time that we cannot get back.

These pandemic days have turned time different. It is no longer really measured in seconds, minutes, hours, days, months. No, in addition to those normal measures of time, we must also reckon with our fears and what we’ve become, what we learned to do to dampen them: We wear masks. We social distance. We text. We Zoom.

As an aside, I’ve literally been on 7,000 Zoom calls over the past eight months. People who used to call me on the phone send me Zoom invitations for no reason at all. My mother says “Dwayne, will you Zoom with us tonight?” “But you have my phone number!” “But isn’t that what the young kids do? Don’t you all Zoom?”

We searched for herd immunity and my best friend is UberEats. I imagine that for many of you, the dream was to go off to college. And time almost becomes a thing that feels suspended, the four years allowing you to grow without real awareness of the outside world. COVID-19 has changed that. Some of you have been forced to return home. To study and write and be a college student while your parents went off to work or didn’t. While your siblings went off to school or didn’t.

In America, no one understands time like prisoners. I know. I stood for count more than 5,237 times over the eight years I spent in prison. I remember how cells slowed time in ways similar but so distinct from COVID. I know that the graduates here, their parents, that we all understand some of that burden now. Understand what it means to not know when or if you will walk amongst your friends again.

And yet, there’s something about time that shows us our mettle. I mean, who could really study amidst such a tragedy? And yet you did. And, amongst you, amongst the graduates in the year 2021 from Wesleyan University, are eight students who were recently or are still incarcerated at the Cheshire Correctional Institution. It’s wild. I used to walk into that prison sometimes to teach with professor Lori Gruen. I don’t believe I expected to see them amongst you. And that is my own failure. But it’s true.

For the first time in history, really, the students who are graduating understand something of what these men in prison turned baccalaureates have experienced. Chasing freedom through education, all while wondering if they’d ever walk outside and feel safe again. Today, these men, some of whom have known more years in prison than free, should know that their fellow graduates understand a little bit of what it meant for them to study inside.

Imagine, many of them have been a part of the Wesleyan community for longer than you. They have toiled away in cells where they didn’t control the lights. In prisons where they could not find a moment of silence. They have literally never touched a laptop. They have worked a class or two at a time, some for more than a decade to make it here with you. Their work reminds me of your work, of believing that education matters enough to keep doing it even as the world is falling apart. I have not seen my mother, my grandmother, my aunts, in more than a year. And I’m certain many of you understand that. And I’m certain now many of you understand what it meant for them to pursue an education while often unable to see their mothers, their fathers, their families, for years on end.

Every graduation speech (according to the speech-making manual they gave me) must have a lesson. Here is mine: Understanding time means understanding the duty that we owe each other. That is to say, right now you are surrounded by friends, families, peers; and over these past months, time has warped what duty is. So much so that all we have is duty.

I believe I disappeared to much of the world while I was in prison. And I believe I reappeared through the education I received in college. You all graduate, those who have not been incarcerated, those who have been incarcerated, and those who are still incarcerated. And suddenly, what time has always been, is the same for everyone. I think you all recognize that a college degree has never been the result of four or five years or even a decade. A college degree has been the result of understanding that if you wake up with two minutes left to get to class, you can make it. (I really thought that was going to be hilarious!)

I want to apologize. After this speech, I’ll race off this stage and jump on another Zoom call with the Virginia parole board. I’m representing a man who went to prison as a teenager, in 1995. He’s been inside for more than 25 years and I’m tasked with finding the words to convince the parole board to let him go home. He calls me “Shahid.” Everybody in prison calls me “Shahid.” It means “witness” in Arabic, it means that he knows me from the time I spent in cells. Because of that time, I feel that it is my duty to do something for him. And that is why I will be racing off this stage.

But I guess the lesson that I wanted to leave you with is: When I graduated from the University of Maryland, I didn’t know what my duty was. In fact, I had told most of the people I knew that I was done with college. Three degrees later, I stand here before you recognizing I was not done with college. I stand here before you recognizing that that accumulation of degrees was me trying to determine what my duty is. I think only time helps us find our duty. So I hope that you walk away today knowing that this is just a start to figuring out what you’re meant to do in the world, but what a glorious start it is.

Thank you.