Student Researchers Discover Potential “Plastic-Eating” Bacteria on Campus

A team of researchers at Wesleyan has discovered new strains of bacteria—located on the University’s campus—that may have the ability to break down microplastics and aid in the world’s ongoing plastic waste crisis.

Microplastics, which measure less than .20 of an inch, enter the ecosystem— and our bodies— largely through the abrasion of larger plastic pieces dumped into the environment. According to a study published in the Journal of Environmental Science and Technology, the average person consumes at least 50,000 particles of microplastic a year and inhales a similar quantity.

“Plastic is typically classified as a non-biodegradable substance. However, some bacteria have proven themselves to be capable of metabolizing plastics,” said Chloe De Palo ’22. “Ultimately, through our research and experiments, we hope to find an effective method of removing plastic pollutants from the environment.”

De Palo ’22, along with Rachel Hsu ’23; Claudia Kunney ’24; and biology PhD candidate Fatai Olabemiwo are members of the Cohan Laboratory in Microbiology, led by Fred Cohan, Huffington Foundation Professor in the College of the Environment, professor of biology. The team has spent almost two years working on a project titled “Isolating Potential Plastic Degraders from a Winogradsky Column.” They presented their most recent findings at Wesleyan’s Summer Research Poster Session.

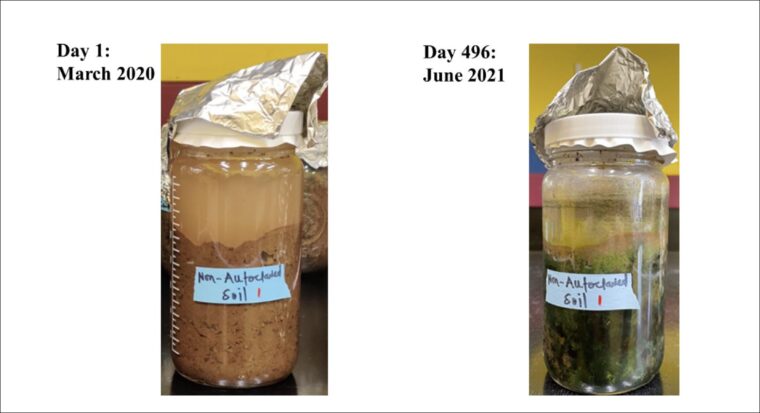

On March 7, 2020 the research team gathered soil samples from Wesleyan’s Long Lane Farm. They placed samples of the agricultural soil, along with plastic strips, inside a modified Winogradsky column, a microbiological tool for culturing broad microbial diversity. The device—invented by Russian scientist Sergei Winogradsky in the 1880s—is still commonly used today to culture bacteria from natural soil and sediments.

“We modified this wonderful device to yield a range of plastic degrades by placing plastic strips at four different zones inside the column,” Olabemiwo explained. “Then we added a medium called Bushnell-Haas Broth, which contains all the requirements for the growth of the microbes except for carbon, to the modified device.”

Now that the columns are sealed, it’s time to wait—for 16 months.

“During this time, we expected the bacteria to ‘tickle’ the strips and eventually adhere to the strips,” Olabemiwo said.

The experiment worked surprisingly well. After 496 days in the soil-broth mixture, Cohan Lab members removed the plastic strips aseptically. Not only did they weigh less, proving that bacteria were effectively decomposing the plastic, but the strips also hosted a diverse community of bacteria from which the lab members isolated 146 strains.

While the majority of the bacteria cultures could be identified through the National Center for Biotechnological Information (NCBI) taxonomy browser, the researchers learned that 24 were discovered species but not characterized and classified, and 28 were novel, undiscovered species.

“We’ll actually be naming them, genomically sequencing them, and adding them to the NCBI taxonomy browser, ” Cohan said.

Now that each bacterium is isolated, the Cohan Lab is working this fall to confirm their potential plastic-degrading abilities by feeding them minute plastic discs in a petri dish. If confirmed, the “plastic-eaters” could help biotechnological companies create a product that could remove microplastics from the environment.