Neuroscience and Behavior Capstone Focuses on Service

“Let’s pass around the brains, but please be careful,” Jennifer Cheng ’11 says. “They break easily.”

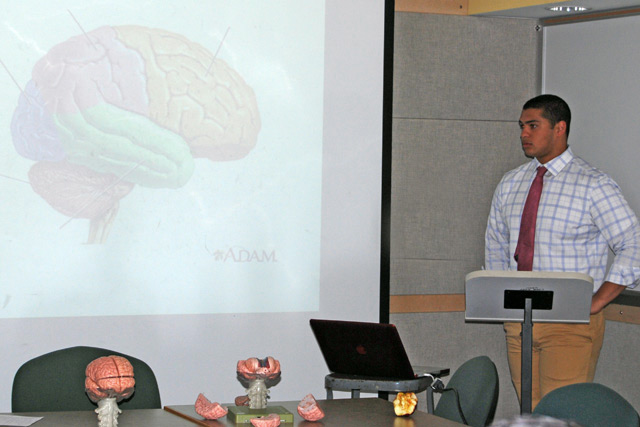

Maryann Platt ’11 and Mandela Kazi ’12 hand out the brains, detailed plastic models with interlocking, removable pieces that allow anyone picking them up to study the organ’s specific areas.

“I don’t think you need to use the stands,” says Janice Naegele, professor of biology, professor of neuroscience and behavior. “I think you can just give them the brains.”

The students nod and make a note and return to their presentation, titled “The Human Connectome Project,” which focuses on the brain, connectomes and the new 3-D technology being used to better map both. The presentation is a practice session that the other students in the class, Neuroscience and Behavior (NS&B) 360, watch and then give feedback. The real thing came a few weeks later in front of high school students, an event that the NS&B 360 students have been anticipating all semester.

NS&B 360 is a new offering this year, a combination capstone course – an intense, rigorous experience that is cumulative and requires students to draw on their previous coursework – as well as a service-learning course, which combines active learning with providing a service to the local community. Naegele created it with the help of Suzanne O’Connell, associate professor of earth and environmental sciences and director of Wesleyan’s Service Learning Center.

“Suzanne would often describe her passion for outreach and I always thought it would be interesting to try to create a service learning course,” Naegele says. “But it wasn’t until I was designing this capstone course last summer that I figured out a way to incorporate a service learning module into one of my neuroscience courses.”

NSB 360 focuses on how experience shapes the brain. Naegele thought that experiential learning through teaching would provide a perfect way for her students to incorporate the scientific concepts introduced in the course’s lectures.

Naegele worked with O’Connell to gain insights into how to structure the service learning experiences, and with Cathy Crimmins Lechowicz, director of Community Service and Volunteerism, to identify area high schools where neuroscience students could make presentations.

“I was excited that Jan was thinking of incorporating a service learning component into the NSB capstone and thought that her students explaining some difficult topics to high school students was wonderful,” O’Connell says. “Often high school science courses don’t convey the excitement and creativity that is so important to science, and I knew these students would.”

In the course, the NSB 360 students examined three basic questions:

– How does neural activity and visual experience transform visuospatialmaps in the brain?

– What synaptic signaling molecules are regulated by neural activity and experience, and what causes these signals to become dysfunctional in developmental disorders affecting cognition and learning, such as autism, Angelman’s syndrome, or Williams syndrome?

– How do exercise and the environment influence the structure of the hippocampus and memory?

The class unfolded in stages, each designed to get the students to create and refine their presentations.

It began with lectures by Naegele and other scientists, including parent and Wes alum Michael Greenberg, on how experience shapes gene expression in the brain. The students then had to read scientific papers on each subject and write a blog or a scientific commentary. Naegele and the course writing tutor, Kelsey Tyssowski ’11, went over all the student writing , editing the texts and making suggestions on organization and approach, then students revised their writing. The writing intensive nature of the course provided students with another mechanism for learning how to explain complex information to non-specialist audiences. Next the students were charged with designing a presentation aimed at high school students. The topics were based on the course lectures, readings, and writing assignments and students formed groups to create their 50-minute presentations. Working in 3 or 4-person groups to design coherent lectures aimed at bright high school students presented unique challenges for Naegele’s students.

“We really attempted to divide the information equally based on comfort with the knowledge,” says Mandela Kazi ’12. “Our hope was that what we teach would pique their interest in neuroscience.”

Naegele also had Crimmins Lechowicz visit the class and talk about effective presentations, including how to dress and speak, making eye-contact with the audience and including audience members in the presentation.

Crimmins Lechowicz also helped Naegele create liaisons between Mercy High School and Xavier High School in Middletown and find classes that would be appropriate for the presentations. Naegele also set up two presentations in biology and psychology classes at Hopkins School in New Haven.

“The service learning component of the course was challenging because the Wesleyan students needed to take a complex subject and figure out how to teach it to high school students,” Naegele says. “At the same time, they had to shift from student role into teacher-role model mode.”

Which brings us back to the practice sessions. As the students rehearsed their presentations, Naegle pointed out how to make transitions between team members during their presentations, staying on schedule, making the presentations more interactive, and other details such as how they would assess student’s learning and retention.

As for the final presentations themselves, feedback from students and teachers at the three schools was overwhelmingly positive.

Kelly Cox, a teacher at the Hopkins School wrote Naegele after the presentation saying, “That was awesome!” and telling her that the Wesleyan students “really knew their audience and adjusted the level of complexity perfectly.”

The comments from students in the high school science classes were equally enthusiastic and laudatory. And the schools are already asking for new presentations for next year.

“High school juniors and seniors are interested in meeting Wesleyan students and learning about their majors and interests at the college level,” Naegele says. “My students have also been talking about the neuroscience major at Wesleyan when they visit these high schools. I think it was a great experience for everyone involved.”