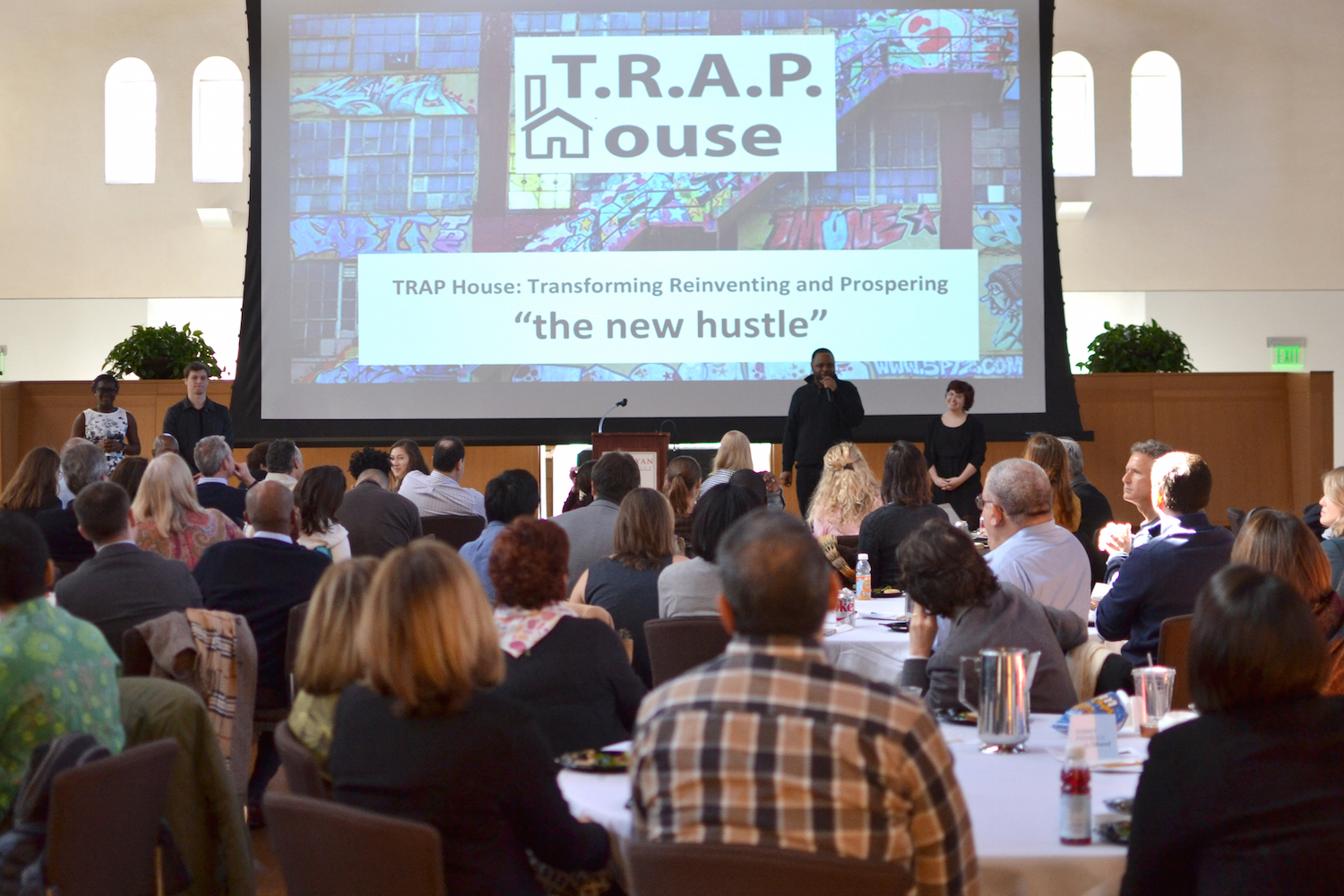

Wesleyan’s T.R.A.P. House Business Incubator Working in Hartford’s North End

The Hartford Courant has featured the work of T.R.A.P House, a nonprofit business incubator that targets high-crime, high-poverty areas and has recently started working in the north end of Hartford. T.R.A.P. House is the creation of a team from Wesleyan: Irvine Peck’s-Agaya ’18, Gabe Weinreb ’18, Sara Eismont ’18, and Bashaun Brown, a former student in Wesleyan’s Center for Prison Education, where he earned 16 credits while serving six years at the Cheshire Correctional Institution for bank robbery.

Brown will be a member of Wesleyan’s Class of 2018, starting in the fall.

T.R.A.P. stands for “transforming, reinventing and prospering,” and is a play on the street slang for a place to buy and sell drugs. According to the Courant:

The acronym doubles as the organization’s mission statement. Brown wants to set up shop in the North End and recruit drug dealers, providing them an outlet to “pivot their skills to the legal economy” through college-level entrepreneurship classes.

He has already started to make his rounds, visiting halfway houses and touring neighborhoods, spreading word of what he’s doing.

“There are no headhunters looking at these people, no one’s looking to hire them,” Brown said. “But I believe you have the same type of people in these neighborhoods that have the same business acumen that you might find at Harvard or Yale. They’re just using it for the wrong reasons.”

Brown knows this all too well from his upbringing on the streets of Plainfield, N.J., a city 30 miles south of Newark where “preteens act as lookouts and drug mules in exchange for soda-and-chip money.” He tried to distance himself from this life by enrolling at Morehouse College, but after one year, “his dreams collapsed under the weight of debt.” He returned home and made a series of bad decisions that ultimately landed him in prison.

There, “I looked back on my life and I realized I had wasted my natural abilities doing the wrong things,” he said. “I wanted to do some good, to give another option to kids growing through that life.”

After his release in July, he stayed in touch with his Wesleyan professors from the Center for Prison Education. This spring, he and the three undergrads submitted the concept for T.R.A.P. House into the Patricelli Center for Social Entrepreneurship’s annual Seed Grant Challenge. It won $5,000 in funding, and received an additional $25,000 from the center’s namesake, Bob Patricelli. According to the Courant:

“I have to believe that Bashaun understands the psychology of young drug dealers and what will appeal to them,” Patricelli, the founder and chief executive of Women’s Health USA, said. “This is not some academic expert writing papers about something. This is a young man who’s lived it.”

The health care entrepreneur saw himself in Brown’s charismatic approach to business. He was immediately attracted to his story of overcoming his past missteps and working to better the world around him.

So Patricelli became an angel investor for the team, something he’s done only once before for a group out of Wesleyan. But his money, which covers program costs and Brown’s salary, came with a single string attached.

T.R.A.P. House had to open in the North End of Hartford, an area Patricelli is interested in bolstering. The group sat down with Mayor Luke Bronin in April, receiving his blessing and a few bits of advice on how to hit the ground running.

“I think Bashaun’s correct that, by definition, street hustlers are entrepreneurs,” Patricelli said. “It’s not enough to create jobs that are in the nature of neighborhood beautification. If you’re going to fire the imagination of young people, they’re more likely to be excited by something they’re familiar with and interested in.”