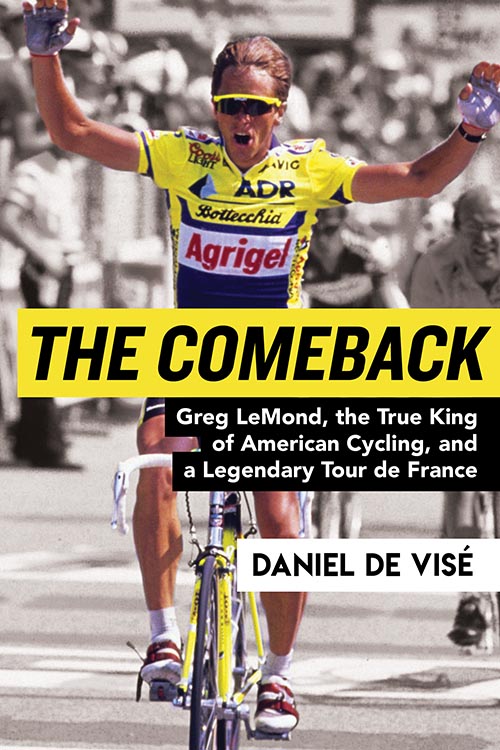

Excerpt: De Visé ’89’s The Comeback: Greg LeMond, The True King of American Cycling, and a Legendary Tour de France

As the Tour de France continues, we hope you enjoy this excerpt from the book by Daniel De Visé ’89, which chronicles Greg LeMond’s 1989 victory. Kirkus Review writes, “It’s a pleasure to ride in the peloton alongside LeMond, who emerges from this account as America’s once-and-future cycling great.” Also see our exclusive Q&A with the author.

ON A SMALL PATCH OF BLACKTOP in a crowded plaza near the grand palace of Versailles, two riders pedaled bicycles in a warm-up exercise around a tiny oval, riding counterclockwise at opposite poles, like horses on a carousel. Their eyes never met. The two figures were almost mirror images—blond-haired, muscular, and taut.

After twenty days and three thousand kilometers of racing, Greg LeMond and Laurent Fignon sat fifty seconds apart in the standings of the 1989 Tour de France. They had traded savage attacks over the three previous weeks, neither man ever leading the other by more than mere seconds. The lead had changed hands three times. Greg had worn the maillot jaune, the race leader’s yellow jersey, for seven days; Laurent had worn it for nine. Now, the jersey hung on Laurent’s back, and Greg was in second place. By day’s end, the Tour would be decided. And no matter who won, this would likely be the closest finish in the seventy-six-year history of le Tour.

On this July afternoon, the circling cyclists readied for a final twenty-five-kilometer dash downhill from the royal chateau to the finish line on the Champs-Elysees in Paris. They would ride at the end of a sporadic procession of 138 cyclists, starting a minute or two apart, each man racing alone as the clock ticked. This was the time trial, cycling’s Race of Truth, in French the contre la montre—literally, “against the watch.”

Savvy observers had surveyed the course and reckoned a middling rider could complete it in about twenty-nine minutes. A great one might win it in twenty-eight.

Greg needed to reclaim those fifty seconds from his French rival on this final day of racing—to pull back two seconds for every kilometer raced—in order to win the Tour.

For most of the three weeks prior, Laurent had pedaled within the protective cocoon of a great cycling team, Super U, a nine-man squad with talent and depth. Greg, by contrast, rode for the pitiful ADR team, a motley crew of sprinters and second-raters. Yet, in this final contest, teams wouldn’t matter. Each cyclist would ride alone. And Greg was better at time trials than Laurent. In previous matchups, Greg had pedaled more swiftly than Laurent by a margin of roughly one second per kilometer of racing. That meant he could expect to beat the Frenchman by perhaps twenty-five seconds today.

But twenty-five seconds would not be enough. To most observers, Laurent had already won the Tour. His lead felt insurmountable.

Both Greg and Laurent were men of twenty-eight—young adults in the broad scheme of life, yet aging journeymen in the brief and brutal career of cycling. Each had conquered le Tour before, Laurent in 1983 and 1984, Greg in 1986, each, in turn, enjoying a brief reign atop the precarious pecking order of professional cycling. Then each cyclist had abruptly lost his “form,” a term invoked by cycling writers to describe a rider at his peak. Both had dwelled for years in cycling’s wilderness, missing races, abandoning them, or finishing at the back of the pack. Now, at the signature event of the 1989 cycling season, each rider had miraculously recovered his form. Greg and Laurent were back on top—both of them, at exactly the same time, a most inconvenient coincidence. Neither knew how long the second wind might last. If there was to be another victory at the Tour for either man, the time was now.

As the clock wound down to Greg’s 4:12 p.m. start, television commentators interviewed cycling experts and one another, all asking the same question: Could LeMond catch Fignon?

“It will be close,” predicted Paul Sherwen, a former professional cyclist turned broadcaster, speaking on the Channel 4 transmission in Britain. “But I think, logically, it’s got to be Fignon.”

Phil Liggett, Sherwen’s broadcasting partner, weighed in: “LeMond is a very determined competitor, and he will not give up the fight for this final yellow jersey. One thing I’m very confident about, and that is this Tour de France will be the closest finish in the history of the race. It could be decided, you know, by five or six seconds, and that would be absolutely unbelievable.”

At 4:11 p.m., Greg rolled to the starter’s gate, a structure that resembled a backyard shed. He wore a streamlined teardrop-shaped helmet of his own design. A pair of odd-looking, U-shaped handlebars jutted out from the front of his candy-apple-red Bottecchia time-trial bicycle. The “tri-bars” set Greg apart; none of the European teams used them.

A man in a pink sports shirt held Greg’s bicycle atop the starting ramp as another man counted down seconds on his fingers. Greg reached down to check that his shoes were locked into his pedals. In those last seconds, thoughts swirled through his head: I don’t like doing time trials. I don’t know if I can do this again. I’ve got to push myself to the limit for the next thirty minutes. Oh, my God.*

And then Greg was off, rolling down the ramp, out of his saddle, pushing his pedals with the full weight of his body until he reached a cadence of one hundred revolutions per minute along the Avenue de Paris.

Greg lowered his torso and stretched out his arms along the aerodynamic bars. He rode on a 54×12 gear: fifty-four teeth on the bigger front gear, twelve teeth on the smaller rear sprocket, a huge ratio that pushed the bicycle more than three meters for every turn of the pedals. Greg’s gear, one of the largest on the road that day, allowed him to accelerate past fifty kilometers per hour without spinning his legs at an uncomfortable speed.

An ungainly cyclist, Greg bobbed up and down as he sped forward, periodically raising and lowering his head, almost as if he were swimming the crawl.

“I wonder what on earth he’s thinking about, now, every time he looks down,” Phil Liggett mused on British television, pondering Greg’s odd cadence.

Greg wasn’t thinking. He was tucking his head down to create the maximum aerodynamic advantage, then raising it just long enough to follow the white line on the road and keep his bicycle pointed in the right direction—exactly as if he were swimming the crawl.

A minute later, Laurent strode up to the starter’s shed. He looked proud and Parisian. But he felt sore, tired, and fretful, and he endured a silent scream of agony as he mounted the saddle of his bicycle. Unbeknownst to competitors and fans, Laurent was suffering from a saddle sore, a raw welt of flesh just where his left buttock met the seat of his bicycle. Doping rules precluded proper painkillers. So he swallowed the pain, as cyclists always did, exhaling slowly and deliberately as he prepared to ride forth.

Laurent had chosen to forgo an aerodynamic helmet, liberating his trademark blond ponytail to flap in the breeze, a concession to vanity as he greeted the Parisian throngs. He rode with two disc wheels; Greg had elected for just one. Cyclists replaced spokes with these solid sheets of carbon to minimize wind resistance in a time trial, but the wheels also caught the full force of any crosswind, and this was a windy day. Laurent rode on a traditional time-trial bicycle with lateral, upturned handlebars. That handlebar choice, so seemingly trivial at the time, would loom large in Laurent’s thoughts by day’s end.

At 4:14 p.m., Laurent pushed off from the gate. As he began to pedal, a fierce pain shot up from his saddle through his body. Cyclists are professional masochists, expert at sublimating pain. Yet Laurent could not ignore this one: “It was like being stabbed with a knife; every part of my body felt it, even my brain.” **

In the broadcast booth, Paul Sherwen said, “It’s a pity we can’t get inside Fignon’s mind to see what’s going through it.”

Phil Liggett replied, “Pain, I would think, Paul. Nothing more than that right now. He’s shutting out everything else.”

Laurent tried to think past the pain to the moment when the torture would end, half an hour later, at the finish, and his victory at the Tour de France would be secured.

Up ahead, Greg, too, focused on the finish. His mind would admit nothing else: not victory, nor defeat, nor the series of events, fortunate, misfortunate, and miraculous, that lay behind him.

*Samuel Abt, LeMond: The Incredible Comeback of an American Hero (New York: Random House, 1990), 190.

**Laurent Fignon, We Were Young and Carefree, trans. William Fotheringham (London: Yellow Jersey Press, 2010), 18.

THE COMEBACK: GREG LEMOND, THE TRUE KING OF AMERICAN CYCLING, AND A LEGENDARY TOUR DE FRANCE © 2018 by Daniel de Visé. Reprinted with the permission of the publisher, Atlantic Monthly Press, an imprint of Grove Atlantic, Inc. All rights reserved.