O’Connell Works with International Scientists to Collect Sediment Cores from Scotia Sea

As campus was winding down for spring break last semester, Professor of Earth and Environmental Sciences Suzanne O’Connell was packing her bags for a two-month expedition in the Scotia Sea, just north of the Antarctic Peninsula, to drill for marine sediment miles below the ocean waves.

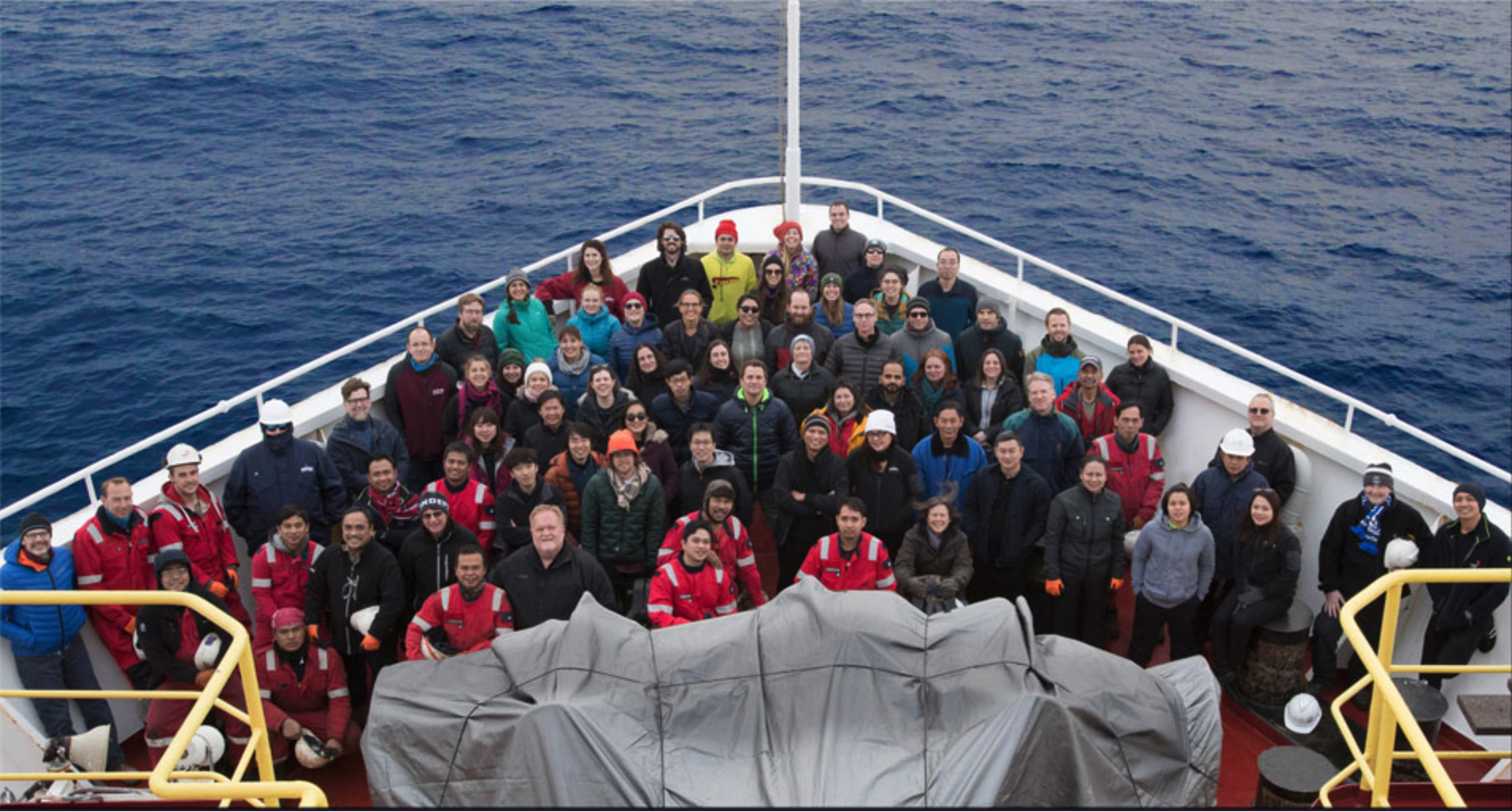

On her ninth expedition since 1980, O’Connell was one of 30 international scientists working 12 hours a day, seven days a week, navigating “Iceberg Alley” aboard the JOIDES Resolution research vessel. It is the only ship in the world with coring tools powerful enough to extract both soft sediment and hard rock from the ocean floor.

At five carefully selected sites the ship stopped, and—provided the vicinity was iceberg-free—scientists lowered coring equipment through an opening in the floor of the ship to drill 0.5 to 2.5 miles down through the water and into the ocean sediment. After two hours, the equipment (which uses an action similar to that of coring an apple), would bring back the 31-foot-long core. Back on board, the cores were cut into 1.5-meter segments and then split lengthwise to reveal a layer cake of preserved mineral and organic sediment, each layer representing a snapshot of the ocean floor from a moment in geologic history.

O’Connell and her lab at Wesleyan focus on the sediment layers from approximately three million years ago, the last time atmospheric CO2 was as high as it is today. Although each of the researchers from 13 different countries have a different area of focus, they are united under the goal of understanding how quickly the Antarctic ice sheets formed and melted in the past. As O’Connell explains it, this information is important to not only international scientists, but also the global public. “We know that two ice sheets, Greenland and Antarctica, hold about 65 meters of sea-level rise. If they are going to disintegrate in 10,000 years, that is very different than in 500 years. We’re trying to get information to constrain how fast they will melt.”

Although the science itself is standardized across borders, the collaborative spirit (and close quarters) of the JOIDES Resolution created a unique environment for building international relationships. “It’s like the UN on the space station,” O’Connell explained. “You get to talk to people about their own countries as well as their scientific work, and how their careers progress in different countries.”

These partnerships translate into opportunities for scientists as well as science students. It opens pathways for sharing instruments that are in short supply because of their narrow function or price tag.

In September, Tristan Stetson ’20, a student in O’Connell’s lab, sent samples to the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ South China Sea Institute of Oceanography for analysis using the institute’s particle size analyzer. Partnerships also help find a home for the components of samples that fall outside a lab’s focus. With other shipboard scientists from Lamont Earth Observatory, Stetson and Eduardo Centeno ’19 perfected a method for extracting the remains of dead plankton from marine sediment samples without causing damage, so that they may be sent to the Institute of Geology ETH in Switzerland for further analysis by paleontologists. Finally, these connections could mean new opportunities for Wesleyan students to intern abroad at labs that are also investigating Antarctica in the deep past.

O’Connell is particularly excited about a new Wesleyan program, “India 2020/2021 Faculty Learning Communities,” which in January 2021 will send her and other STEM colleagues to India to develop collaborations with scientists like fellow sedimentologist Shubham Tripathi, whom she met while onboard the JOIDES Resolution.

“People often think of scientists in the lab, right? You know, with their white coat on and just working by themselves,” O’Connell said, reflecting on her two-month excursion. “This is an international group with all these other hundreds of people involved, and I think that part is great.”