Biology Researchers Study Connecticut’s Native Fish Populations

There’s something fishy about one of Connecticut’s minnows, and the topic hooked researchers in the Department of Biology.

During the last ice age, Connecticut was covered by layers of snow and ice, forcing organisms to seek refuge elsewhere. After the glaciers retreated, recolonization of the fauna and flora resulted in the diversity of native species that inhabit the state today.

“But where did they come from? How did they come back to the Northeast to give us all the organisms we see today?” asks biology graduate student Michelle Tipton. “These questions are of particular interest to the ichthyologists at Wesleyan with regards to fishes.”

In an upcoming issue of Ecology and Evolution, a scientific open access journal, faculty and students provide some of the first genetic evidence of what took place during the most recent post-glacial recolonization events, which provided Connecticut and the northeast with its native fish populations. To begin filling the void of information for this large biogeographic question, they started their research with this ubiquitous minnow. The manuscript is titled, “Post-glacial Recolonization of Eastern Blacknose Dace, Rhinichthys atratulus, Through the Gateway of New England.”

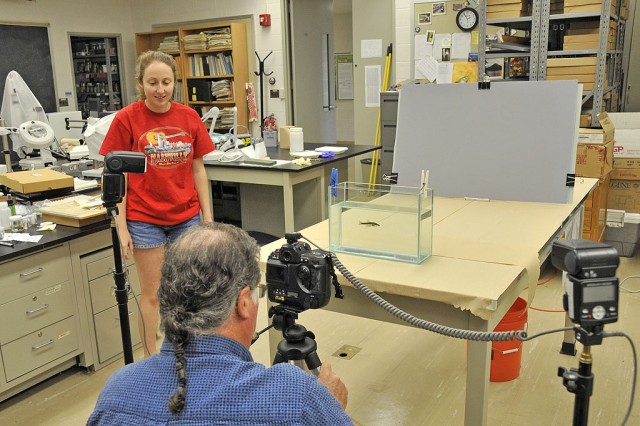

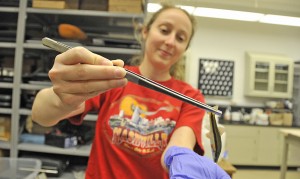

The Eastern Blacknose Dace is a small minnow that can be found in high numbers in most freshwater streams in Connecticut and throughout the Northeast.

Tipton is the lead author of the study, along with Phoebe Stonebraker ’11, Sarah Gignoux-Wolfsohn ’10 and Barry Chernoff, the Robert Schumann Professor of Environmental Studies and director of the College of the Environment.

The paper is also the first chapter of Tipton’s dissertation for which she has focused on determining the number of recolonizing populations of Eastern Blacknose Dace and recolonization events that occurred in the state’s major drainage basins: the Housatonic River, the Connecticut River and the Thames River. These basins were the first to become deglaciated in New England.

“Ultimately, we concluded that Connecticut was founded by one population of Blacknose Dace during a single event and then, much later, a second recolonization event occurred. This second event is interesting because it was isolated to the Housatonic drainage basin and brought in Dace that were genetically distinct from the original founding population which instead matched Eastern Blacknose Dace from all over New York,” she says.

This summer, Tipton presented the group’s findings at the annual Joint Meeting of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists in Minneapolis, Minn.

Tipton’s broader dissertation objective is to determine the location of the glacial refugia that supplied the population recolonization of the entire northern distribution of this fish, the Eastern Blacknose Dace. This species’s distribution runs from North Carolina to Nova Scotia, primarily east of the Appalachians. However, during the last ice age, the northern half of this distribution was covered by the glaciers. She now has over 800 fish samples from all over the eastern United States and eastern Canada, including Nova Scotia. Here, latest data show the glacial refugia, for Eastern Blacknose Dace that now live in the northeastern region, to have been in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, just below the farthest extent of the glaciers during the last ice age.