5 Questions With . . . Joe Siry on Frank Lloyd Wright’s Religious Architecture

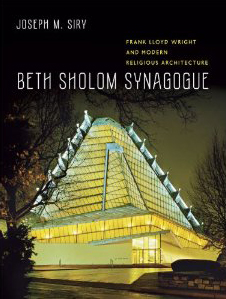

This issue, we ask 5 Questions of Joseph Siry, chair and professor of art and art history. Professor Siry teaches classes about modern and American architectural and urban history. His book, Beth Sholom Synagogue: Frank Lloyd Wright and Modern Religious Architecture, was published by the University of Chicago Press in December 2011.

Q: In your newly-published book, you provide an in-depth look at architect/designer Frank Lloyd Wright’s Beth Sholom Synagogue in Elkins Park, Penn., which was constructed in 1959 and is considered one of his greatest masterpieces. What prompted you to write a book about this structure in particular?

A: I first saw Beth Sholom in 1980 and was hugely impressed with its main auditorium as a space for worship. Its design and construction toward the end of Wright’s long life was formally and technically unprecedented. It also represented a culmination of his involvement with religious architecture, so the book includes chapters on a number of his earlier related church and theater designs, going back to his original participation in the design of Chicago synagogues in the 1880s.

Q: The synagogue was designated a National Historic Landmark in 2007. What makes this building unique and how does it compare or contrast to other Frank Lloyd Wright designs?

A: Beth Sholom is unique in its tetrahedral steel structure that creates a large main auditorium whose dome is almost entirely of translucent glass. Wright had experimented with such an idea in earlier unbuilt projects, but Beth Sholom was his only synagogue and the largest free span that he ever realized, yet its seats on floors sloping toward the frontal platform create a communal space that developed from his earlier buildings for assembly.

Q: When did you begin writing this book, and how did you research the synagogue’s background? Also, who would find this book valuable?

A: I began research and writing for this book in 2003, and worked with materials in the synagogue’s archive, in Wright’s archive, and those of churches that he designed in Lakeland, Florida, Kansas City, Missouri, and Madison, Wisconsin, among other sources around the country. This book is meant for readers interested not only in Wright’s architecture, but also in modern church and synagogue architecture, and the relationship between religious communities and their worship rooms.

Q: Frank Lloyd Wright is renowned for designing the Guggenheim Museum in New York, “Fallingwater” in Pennsylvania, dozens of low-roofed “Prairie” style homes in the Midwest, and the Unity Temple in Oak Park, Ill., which you wrote about in 1996. What are other well-known Wright structures that appeal to you? How many have you visited and researched?

A: I have visited about 50 of Wright’s works, including his earlier Prairie and later Usonian houses in the Midwest, Arizona, and California, Fallingwater, his own Taliesin in Wisconsin, and Taliesin West near Scottsdale. Other than the buildings discussed in this book, I have researched articles or essays on the Guggenheim, his no-longer-extant Imperial Hotel in Tokyo (1913-23), the Grady Gammage Memorial Auditorium for Arizona State University at Tempe (1958–64), and his Price Tower in Bartlesville, Oklahoma (1952-56), one of his two vertical towers. I am researching the environmental controls for his office building (1936–39) and tower (1944-50) for S.C. Johnson & Co. in Racine, Wisconsin, among his most innovative works.

Q: You’ve taught at Wesleyan since 1984, and you received Wesleyan’s Binswanger Award for Teaching Excellence in 1994. What are your signature courses at Wesleyan and what do you enjoy most about teaching?

A: The courses on 19th century American and European architecture and urbanism, and on 20th century architecture I have offered regularly since I started teaching at Wesleyan. I began teaching a seminar on Wright in 1993. In 2002 I developed a seminar in historiography, theory, and criticism of architecture, and in 2009 I introduced a course on contemporary world architecture, thematically concerned with how artists in this medium respond to issues of digitization, sustainability, urban development and cultural identity. Like my colleagues, I am enormously thankful for the intellectual engagement of Wesleyan students with their own educations. Their appreciation for our efforts in teaching is rewarding beyond words.