Wesleyan Media Project Provides Political Ad Tracking, Analysis During Election

In the first presidential election since the Citizens United case transformed the campaign finance landscape, the number of ads airing in the presidential race alone surpassed one million by late October.

While 2012 saw a sharp increase in the number of outside interest group players in the election, and corresponding increases in the amount of spending from groups who do not have to disclose their donors, there remained one consistent source of transparency in advertising—the Wesleyan Media Project. A political ad tracking project headed by Assistant Professor of Government Erika Franklin Fowler and colleagues at Bowdoin College and Washington State University, the Wesleyan Media Project provided data and analysis for hundreds of news stories on the election.

“Federal reporting guidelines do not ensure that the public knows who is attempting to influence elections before they go to the ballot box,” Fowler says. “The Wesleyan Media Project’s goal is to provide publicly available information, in real-time, during elections to increase transparency and to better enable citizens to hold various interests accountable.”

The Wesleyan Media Project, established in 2010, is the successor to the Wisconsin Advertising Project, which tracked political ads between 1998 and 2008. The Wesleyan Media Project is supported this year by the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, the Rockefeller Brothers Foundation, and Wesleyan University.

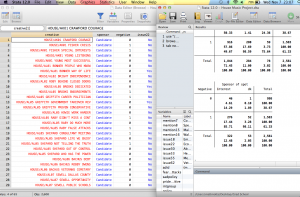

The Wesleyan Media Project purchases raw data on campaign advertising from Kantar Media/CMAG and analyzes it in a number of ways. For all 210 media markets across the country, it counts how many political ads are aired on broadcast and national cable television in support of each candidate, at what cost, and by which sponsor (candidates, parties or “outside groups” like Super PACs and 501(c)(4)s).

But this is just the start. Wesleyan students working in the Quantitative Analysis Center (QAC) in Allbritton do the hard analysis work, answering hundreds of questions about the content of each ad.

Matt Motta ’13, a government major who has been working on the Wesleyan Media Project since fall 2010, explained that some of these variables are very objective (for example, “Does the ad contain an American flag?” or “Does the favored candidate appear narrating the ad?”), while others are more subjective, (“Does the ad make a strong appeal to fear? Some appeal to sadness?”) These subjective variables are trickier to discern, Motta said.

“In order to deal with these, we set standards as to what counts, run through dozens of examples, and standardize our responses through training sessions and discussions,” he explains. The coders use an online system, through which they can watch, pause and zoom in on ads on half their screens while filling in codes on the other. The process typically takes 4 to 7 minutes per ad. Motta estimated that he has watched between 400 and 500 unique ad spots through his work on the Wesleyan Media Project.

Matt Motta ’13 uses an online system to “code” political ads. Motta estimates that he has watched between 400 and 500 unique ad spots through his work on the Wesleyan Media Project.

Motta believes that “Tracking advertising spending and content in federal campaigns is necessary in order to fully understand political life in the United States. Studying political advertising allows political scientists to understand the shared experiences of millions of Americans—exposed to more negativity than ever—and make meaningful judgments about how political tactics affect democratic participation.”

In this election cycle, the Wesleyan Media Project released six separate studies, beginning in January during the Republican primary race. These studies provided political reporters covering the election with valuable insights—identifying the big spenders; showing which key battleground states the money was flowing into; which candidates enjoyed an advertising advantage over their competitors; and the overall tone of ads, among other things. As the months passed, it became evident that the 2012 election would shatter all previous advertising records. Between April 11 and Oct. 29, 1.1 million ads were aired by both political parties in the presidential race, at a cost of nearly $703 million. And in the House and Senate races, between June 1 and Oct. 21, another nearly 983,000 ads were aired at a cost of almost $565 million.

“All expectations were that 2012 would be a record breaking year for political advertising, but record pulverizing is a more accurate descriptor,” said Fowler. “What is perhaps even more striking than the total number is the fact that all of the ads were crammed into many fewer markets than in 2008, leaving many citizens on the sidelines when it comes to the air war.”

Also notable this year was the extremely negative tone of the presidential ad war. From June 1 to Oct. 21, only 14.4 percent of ads run by the Obama campaign, and 20.4 percent run by the Romney campaign, were positive. By contrast, over the same period in the 2008 presidential race, Obama’s campaign ran 37 percent positive ads, and McCain’s campaign ran 24 percent positive ads.

The increased influence of outside groups, such as Super PACs, also was abundantly clear in the Wesleyan Media Project’s analyses. Over the general election period, Obama’s campaign led in the total number of ads aired. While Romney’s campaign sponsored only about one-third of the number of ads run by the President, the Republican was heavily reliant on outside groups to make up the difference. Romney’s biggest outside support came from the Super PAC Restore Our Future, and Karl Rove-backed groups American Crossroads and Crossroads GPS. While American Crossroads is another Super PAC, Crossroads GPS is a non-profit “social welfare” organization whose donors remain anonymous.

“Big contributors, especially on the Republican side, may re-evaluate their donation strategies after this election. While the campaigns are guaranteed the most favorable TV advertising rates, stiff competition for airtime in battleground states means that outside groups end up paying much higher prices for ads—getting less bang for their buck,” said Fowler.

Looking back over the campaign, Fowler said it’s likely that advertising in the battleground states had an impact. She believes that the domination of pro-Obama ads in these key states for much of the campaign accounted for much of the president’s lead in the polls. Pro-Romney advertising only began to catch up near the end of October, though the Obama campaign continued to hold an overall ad advantage in swing states throughout the campaign.

“Like John Kerry before him, Romney may have missed the opportunity to define himself before Obama defined him,” Fowler said. “And given the overwhelming negativity, Romney may have missed the opportunity to give the electorate positive reasons to vote for him before turning on the attack.”

Fowler and her associates will be investigating these questions and others through statistical analyses in the coming months. Motta and other students are also working on research projects using the Wesleyan Media Project’s data.

On Nov. 30, Wesleyan is hosting a conference on Campaign Finance, Political Communication, and the 2012 Election, featuring panel discussions by academics and political reporters. A conference agenda is online here. The event is free and open to the public; RSVP to Laura Baum at lbaum@wesleyan.edu.