Lensing Reviews Biography of Fritz Lang

Leo Lensing, professor of film studies, is the author of a review essay titled “Fritz Lang, man of the eye. On the Edgar Allan Poe of German Cinema,” published in the June 15 issue of the Times Literary Supplement (London). The TLS cover article takes stock of Fritz Lang. Die Biographie (Propyläen Verlag, 2014), the first full-length biography in German of the great Austrian-German filmmaker Fritz Lang (1890-1976), and compares it unfavorably with Fritz Lang. The Nature of the Beast, the standard American life by Patrick McGilligan.

Leo Lensing, professor of film studies, is the author of a review essay titled “Fritz Lang, man of the eye. On the Edgar Allan Poe of German Cinema,” published in the June 15 issue of the Times Literary Supplement (London). The TLS cover article takes stock of Fritz Lang. Die Biographie (Propyläen Verlag, 2014), the first full-length biography in German of the great Austrian-German filmmaker Fritz Lang (1890-1976), and compares it unfavorably with Fritz Lang. The Nature of the Beast, the standard American life by Patrick McGilligan.

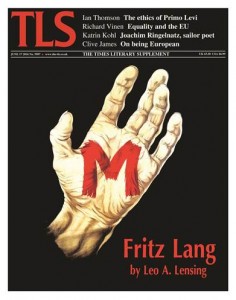

Lang’s reputation, Lensing writes, continues to be linked primarily to two films he made during the Weimar Republic: “the famous blockbuster flop Metropolis (1927)”; and M (1931), “the infamously empathetic profile of a serial killer, which Lang often called his favorite. Metropolis, still often categorized as ‘a flawed masterpiece’ by film scholars, has become even more popular and influential. Every metropolitan dystopia from Blade Runner to Batman Returns owes something to its visionary scenario of a technologically unhinged future.”

Lensing writes that “Grob’s treatment of the monumental making of this ‘urtext of cinematic modernity’ (Thomas Elsaesser) typifies his biography’s modest virtues. Grob’s narrative often veers between compact scenarios and long, thinly fleshed-out lists of people met, films seen, theater performances attended, art exhibitions visited and, especially, women wined and dined. While this enhanced name-dropping with its litany of intellectual, artistic and erotic contacts can be beguiling, the overall effect raises questions of the kind for which a biographer should supply answers.”

“Among the genuine advances that might have been expected from a new biography of Fritz Lang,” Lensing writes, “especially one with easy access to European sources, is more light on the practically blank early years in Vienna. … Grob’s failure to make anything substantial of Lang’s intellectual beginnings in turn-of-the-century Vienna goes hand in hand with a remarkably crude evocation of this filigreed cultural environment.”

“Ultimately, Grob seems more invested in taming Lang the ‘Beast,’” Lensing writes, “even as he holds his rival biographer all too close, than in exploring the hidden and mythified connections between the profligate life and the truly astonishing films. Seizing on Lang’s own words ‘Ich bin ein Augenmensch’ (‘I’m a visual type,’ literally a ‘man of the eye’) for his subtitle, he speculates on the phrase’s evocation of Goethe, the Augenmensch par excellence in German culture and the very model of a well-adjusted artistic personality. In his autobiography, Goethe celebrated the power of aesthetic vision to reconcile the tensions between art and experience announced in its title, Poetry and Truth. This kind of balance proves a poor fit, however, for the fissures and breaks that marked Lang’s messy creative and personal life. Stringent devotion to form and a penchant for excess need not be mutually exclusive.”

Lensing also wrote an article titled “Lehrjahre eines Großmeisters” (“The Apprentice Years of a Great Master”), published in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung on June 29. The article focuses on Fritz Lang’s early career as a graphic artist in Vienna and Munich. Using neglected visual evidence, including a poster designed for the famous Cabaret Fledermaus (1911) in Vienna and a portrait drawing (1917) of the satirical writer Karl Kraus, Lensing traces the connections between Lang’s artistic apprenticeship in modernist Vienna and the media critique in his “newspaper noir” films of the 1950s.