Smith ’66 on Translating and Promoting Global Indigenous Literature

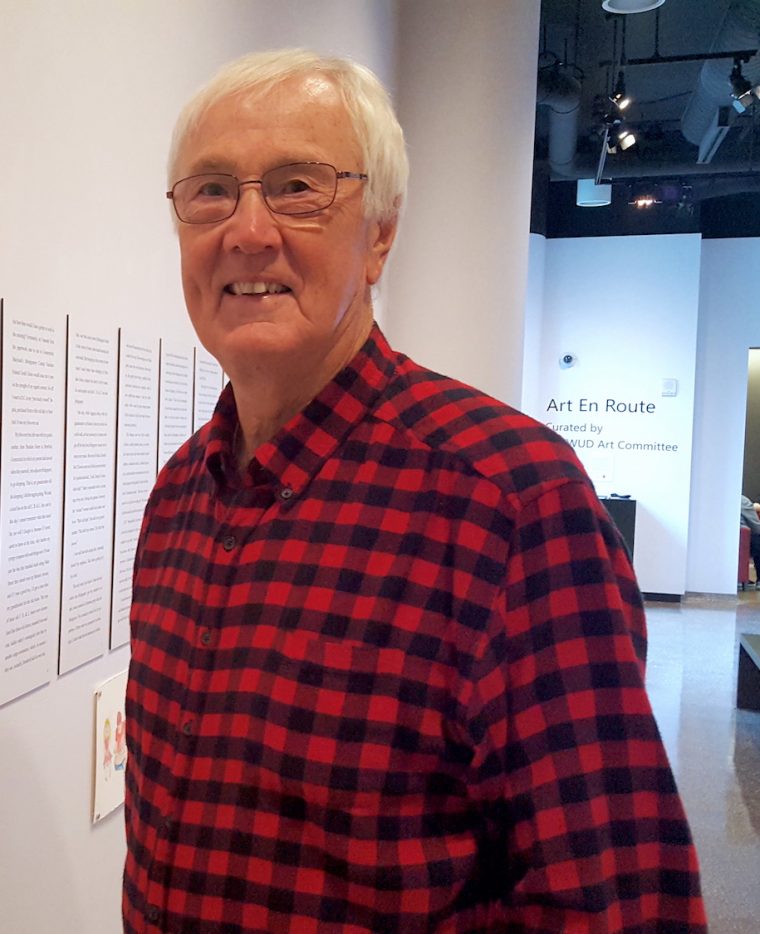

Claude Clayton “Bud” Smith ’66, professor emeritus of English at Ohio Northern University, is an author who throughout his career has worked behind the scenes to bring Native Siberian creative writing to an English-speaking audience and to promote global indigenous literature. In that spirit, before Smith’s story starts, he recommends we tune in to the PBS premiere of N. Scott Momaday: Words From a Bear, on Nov 18.

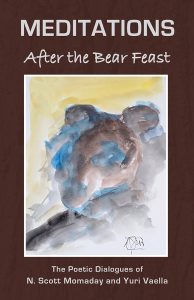

Smith’s connection with N. Scott Momaday is personal. In 2016, Smith co-edited and translated Meditations After the Bear Feast, a collection of poems exchanged between Momaday, a Kiowa writer and the defining voice of the Native American Renaissance in American Literature, and Yuri Vaella, a writer, reindeer herder, and political activist of the Forest Nenets people in western Siberia. But Meditations After the Bear Feast nearly did not see print. How did Smith, a descendant of one of the founders of Hartford, Conn., on his father’s side and an immigrant Czech on his mother’s—who does not speak Russian or any native languages—become the critical player in bringing Meditations to publication? According to Smith, the story begins where it does for every writer, in his childhood backyard.

Smith grew up a 45-minute drive from Wesleyan, in Stratford, Conn. Despite the erasure of Native American history, Smith became aware of his hometown’s long past through local Stratford history and the stories of the Sioux man who rented fishing boats to his grandfather. He remembers that, as a child on a field trip to where the Paugussett tribe first encountered settlers in 1639, “my imagination went wild.”

By 1978 Smith had published his first book, The Stratford Devil, and begun teaching when his mother sent him an article from the Bridgeport Post that mentioned the Paugussett tribe. The tribe had just won a yearslong struggle to protect from termination their quarter-acre reservation—a small remnant of their ancestral lands and the oldest continuous reservation in the United States. The reservation happened to be three miles from where Smith grew up, and so Chief Big Eagle of the Paugussett tribe became the subject of Smith’s first book of creative nonfiction. After hours of taped interviews on the Chief’s front porch, Smith began writing the tribe’s story in the voice of the Chief. Miscommunications often arose; of one such conflict Smith said, “I was discussing the gustoweha (the chief’s headdress), which has antlers. The Chief had evidently led quite a love life, marrying four times, and so when discussing the headdress I commented, in the Chief’s voice, something to the effect that, ‘the antlers remind me of myself as a young buck.’ The Chief fumed, and I changed the line to, ‘reminds me of the deer, a noble animal.'” Through the Chief’s editing of his drafts, Smith learned how to write in another’s voice, a skill that would serve him well in his translating work later. The book, Quarter-Acre of Heartache, was published in 1985, a first-person account from the perspective of the Chief, and today, when Smith reads the quotes on the novel’s rear jacket, “half are the Chief’s actual words, half are mine. I’d so absorbed his voice that I can’t now tell which is which.”

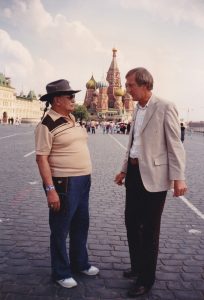

What happened next, neither man could have predicted. At the suggestion of a colleague, Smith gave a copy of the book to Alexander Vashchenko, a Native American studies professor in Moscow. Vashchenko fell in love with the story, translated it to Russian, and invited Smith and the Chief to Russia months after the fall of the Soviet Union. This trip grew into a long professional partnership and friendship between Smith and Vashchenko. They co-edited and translated the first anthology of Native Siberian folklore in English, as well as Meditations After the Bear Feast. Their first publication, in 1995, was a prose chapbook by Yeremei Aipin of the Khanty tribe in western Siberia.

Smith does not speak Russian, so translating Aipin’s chapbook presented a steep learning curve. First, Vashenko would translate the Russian into English. This was easy when Vashenko was visiting the US, but in the early years of their partnership correspondence with Russia was unreliable; mail always arrived opened, if it arrived at all. Next, Smith would adapt the translation for an English-speaking audience. “Whenever the English was ‘fuzzy’—especially due to Russian tenses—I took the Russian text to my colleague in the language department, and we hammered out the problem.” For Aipin’s first chapbook, “I tended to stick to the text too literally.” Over time, and following the insight of a fellow poet also translating foreign work, Smith realized that translating creative writing is a chance to “riff” on another writer’s work. “This encouraged me to loosen up with Aipin’s prose and take a few ‘flights of fancy,’ which became my habit later on.”

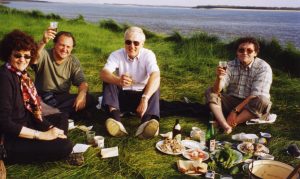

In the spring of 2010, with a few more books and many years of teaching behind him, Smith was at a conference in Santa Fe with Vashchenko as well as students, and Native American scholars and writers from all over the country. Momaday and Vaella had previously met and begun exchanging poems, but it was at this conference that Vashchenko proposed Meditations After the Bear Feast to bring their poetic dialogue to a larger audience. Meditations would rebuild the land bridge and, according to the back cover, “the poetic dialogues contain a mutual recognition of kinsmen across centuries of mutual isolation … [They are] the declaration of fundamental human values, expressing the authors’ deepest aspirations as spokesmen for traditional cultures.”

However, what was meant to be a lengthy exchange of poems was interrupted by Momaday’s health and the deaths of both Vaella and Vashchenko. Although Smith was grieving his friend, “[Vaschenko’s] death made me determined to see that book get published; which I did—as a monument to him as much as a celebration of Momaday and Vaella.” Smith supplemented the four poems they had exchanged with Momaday’s artwork, photographs, a Foreword by Susan Scarberry-Garcia, who had traveled with Smith and Vashchenko in Siberia and who did her doctoral dissertation on Momaday; a critical essay by Native Siberian scholar Andrew Wiget; and two poems by Nathan Romero, a young Native American student who had been inspired by the international breadth of indigenous writing and art he had seen at the Santa Fe conference in 2010.

Beyond honoring Vashchenko’s memory, Smith said, “If the book has any impact, it begins with those poems [by Romero]—with younger Native Americans realizing how their own traditions have an international scope; that they are part of something larger than themselves, with—hopefully—a recognized responsibility to acknowledge, honor, participate in, and further this spirit. Global literature progresses by such fits and starts.”

The United Nations Committee responsible for the Decade of Indigenous Peoples, 1994-2004, recognized Smith as “a Friend of Native Peoples.” But for Smith, “the great opportunity” of working to promote global indigenous literature has been “the expansion of one’s world through another’s.” So that we too may expand our worlds through others, Smith hopes that we catch the upcoming PBS piece on Momaday and also keep an eye out for Smith’s most recent translation of Yeremei Aipin, Mists on the River: Folktales from Siberia, in 2020.