Dolan Studies Impact of COVID-19 on Public Attitudes Toward Globalization

Assistant Professor of Government Lindsay Dolan specializes in international political economy and comparative politics in developing countries. Her research and teaching interests include international organizations, foreign aid, and development. Together with her co-author Quynh Nguyen of Australian National University, she has been studying how COVID-19 is affecting public attitudes toward globalization.

President Trump recently announced that he is suspending U.S. funding for the World Health Organization (WHO). Can you briefly explain the role of the WHO, particularly during a global health crisis, and what will be the implications of the U.S. cutting funding? Which countries or populations will be most affected?

The World Health Organization (WHO), like many international organizations, exists to provide information and coordinate among its 194 member states. Although it works on a host of global health issues, pandemic preparedness is an important part of its mandate. Its role during such a crisis is to collect and disseminate valuable information on the number of cases, provide scientific and technical information to inform government responses, and to establish a forum for coordination among governments.

While member states do pay dues to the WHO, the bulk of its budget comes from contributions its member states choose to voluntarily donate. In 2018, the U.S. provided fully 12.5% of these voluntary contributions, making it the WHO’s biggest donor. Governments that make sizable contributions to international organizations often enjoy greater say over their policy priorities. In other research with Richard Clark, we’ve found evidence of this at the World Bank, an institution that designs development loans that disproportionately benefit friends of the U.S., its largest shareholder.

When the U.S. cuts funding, the WHO will be even less well-equipped to effectively inform and coordinate governments as they respond to this pandemic, or the next. It will also be less prepared to address other health concerns, especially in the developing world, one of its key goals. After cutting funding, the U.S. may also find that the WHO’s policy priorities no longer align with its own. Other countries such as China would be wise to fill this void.

What do we know generally about public support for international assistance? Are there any notable trends?

Foreign assistance is not typically a policy priority, and most individuals in donor countries are fairly uninformed about it. During times of economic crisis, foreign aid is an especially easy target for budget cuts. There is evidence that Europeans who had been hard-hit by the Eurozone crisis were especially opposed to foreign aid.

But those who support foreign assistance tend to do so for either altruistic or self-interested reasons. Some ideologically believe in the merits of international cooperation or helping others; in the U.S. they tend to be Democrats. Others pragmatically support international assistance when they can recognize the benefits they receive. For instance, aid can be used to buy countries’ votes at the UN; or promoting development in other countries may reduce negative spillovers like migration and terrorism. [Those with these reasons for support] tend to be Republicans.

Since the start of the pandemic, you conducted a survey of U.S. public opinion on funding international organizations and aiding developing countries. How were you able to respond so quickly with this survey? And what did your research find?

As the COVID-19 pandemic was unfolding, I was thinking about two lessons I’ve learned from political science: (1) the importance of cooperation in a globalized, interconnected world, and (2) the unpopularity of globalization during times of hardship. COVID-19 appeared to exaggerate both of these elements. I was especially following the impact on developing countries, which are arriving at this crisis with considerably weaker health care systems and far fewer resources to support safety nets, making it challenging for them to adopt the policy tools we see in the U.S. This pandemic has illustrated how easily an outbreak in one region can travel the world, so it seems more important than ever to prioritize the needs of the world’s poorest countries. Nevertheless, if the financial crisis of the last decade is any indication, we should expect to see weakening support for foreign assistance as economic conditions in the U.S. worsen, and perhaps even blaming of globalization for this problem.

In late March, I was discussing these issues with Quynh Nguyen at Australian National University, with whom I’ve previously researched how individuals assign blame for climate change between national governments and international actors. Neither of us had seen any polling being done on these issues, let alone in ways that would allow us to carefully investigate how people were thinking about international engagement. We quickly drafted a survey questionnaire, secured IRB approval and funding from each of our departments, and fielded our survey to 2,500 Americans through Qualtrics, a market research panel I’ve previously worked with. The whole process took about a week to prepare and a week to field.

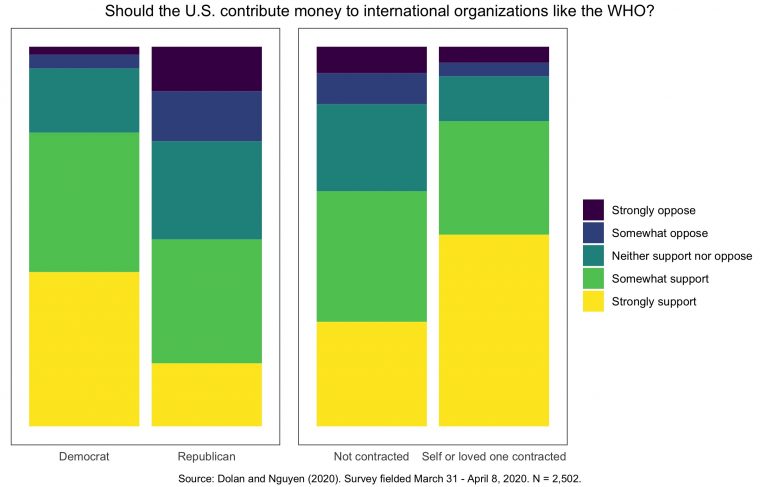

We found that exposure to COVID-19 and partisanship predict individuals’ support for WHO funding and aid to developing countries. Respondents with a higher level of personal exposure to the virus were more likely to support WHO funding, but less likely to support aid to developing countries. Republicans are less supportive than Democrats of both forms of international assistance.

You found that personal exposure to the coronavirus influenced people’s views on international assistance. What do you take away from this finding?

Compared to unexposed respondents, respondents with personal exposure to the effects of COVID-19—through contracting the virus or job loss—are more supportive of WHO funding but less supportive of aiding developing countries. This is interesting because their attitudes toward assistance move in opposite directions, depending on the type of assistance. While we can’t know for sure, what we think is going on is that exposure to COVID-19 makes apparent and quite personal the severity of the problem and the need for the WHO to help solve it. In other words, respondents see how international organizations can benefit them personally. In contrast, aiding developing countries may appear to detract from the government’s ability to respond at home, and exposed individuals may therefore be more reluctant to support this form of assistance.

What are the implications of the partisan nature of support that you found in the survey?

Republicans are less likely than Democrats to support either form of assistance. This partisan bias is not surprising given what we know from the literature and other public opinion polls on COVID-19. But we were especially interested to learn that Republicans’ opinions about funding the WHO are more sensitive to COVID-19 exposure than Democrats’ are. In fact, exposure counteracts the partisan bias, leading to similar support for financing the WHO among exposed Republicans and Democrats. We think that this is consistent with findings from previous research, which indicate that Republicans tend to think about assistance in terms of the benefits it provides in return, while Democrats tend to think about assistance in ideological terms. Exposure to the effects of the virus may nudge Republicans to reassess their self-interest, but does little to change Democrats’ ideologically-motivated beliefs.

If international engagement is critical for effectively responding to this global health crisis, does your research suggest any approaches to bolster support for such efforts?

It’s hard to persuade donor publics to provide assistance during a crisis. But our results suggest that the best way to do so is to remind them of the benefits they receive from this assistance—the ability to influence policy at the WHO, support for WHO efforts to help solve this problem, and reduced vulnerability to negative spillovers from the developing world. Altruistic appeals might resonate with Democrats, but probably not with Republicans. But it’s important to note that our current results are entirely based on patterns we observe in people’s pre-existing attitudes; more work is necessary to test the effectiveness of these appeals.

You’re planning more research on how the pandemic is affecting public attitudes toward globalization. Can you please describe the focus of your future research?

We are planning to field a follow-up survey in six to eight weeks, depending on how current events unfold, to track any changes in individuals’ responses to these and other questions. Using data from both surveys, we are planning to analyze (1) whether exposure to COVID-19 is changing the way Americans feel about globalization (e.g., free trade, immigration), and (2) how individuals assign blame for the handling or mishandling of the crisis between national governments and international organizations.