Bery ’21, Haddad Share Climate Action Plan Study with United Nations

In a new study linked to her 2021 high honors thesis, Sanya Bery ’21 discovered that cities that house universities have a significant likelihood of adopting ambitious climate action plans.

“It is clear that as plans become more ambitious, there is a higher concentration of university cities, and as plans become less ambitious there is a lower concentration of university cities,” she said. “[These cities] efforts will be critical to the world’s effort to combat climate change.”

Bery, who majored in government and environmental studies, is currently collaborating with Mary Alice Haddad, John E. Andrus Professor of Government, on a peer-reviewed article that includes Wesleyan and Middletown climate topics, and on Oct. 14, the duo presented Bery’s findings at the United Nations Innovate 4 Cities Conference.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has warned that CO2 emissions must reach net zero by 2050 to prevent the most catastrophic consequences of global climate change. Cities alone, according to the IPCC, emit more than 70% of the world’s emissions.

In order to study climate action plans, Bery took a tangible, qualitative approach to measure the “ambitiousness” of the action by creating a scorecard. She explored a dataset of 169 cities, nationwide, that are signatories in the Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy. This was in addition to her thesis, where she looked at 66 cities with fewer than 100,00 residents.

“I wanted my research to focus on a more localized lens: smaller municipalities’ role within climate policy,” she said.

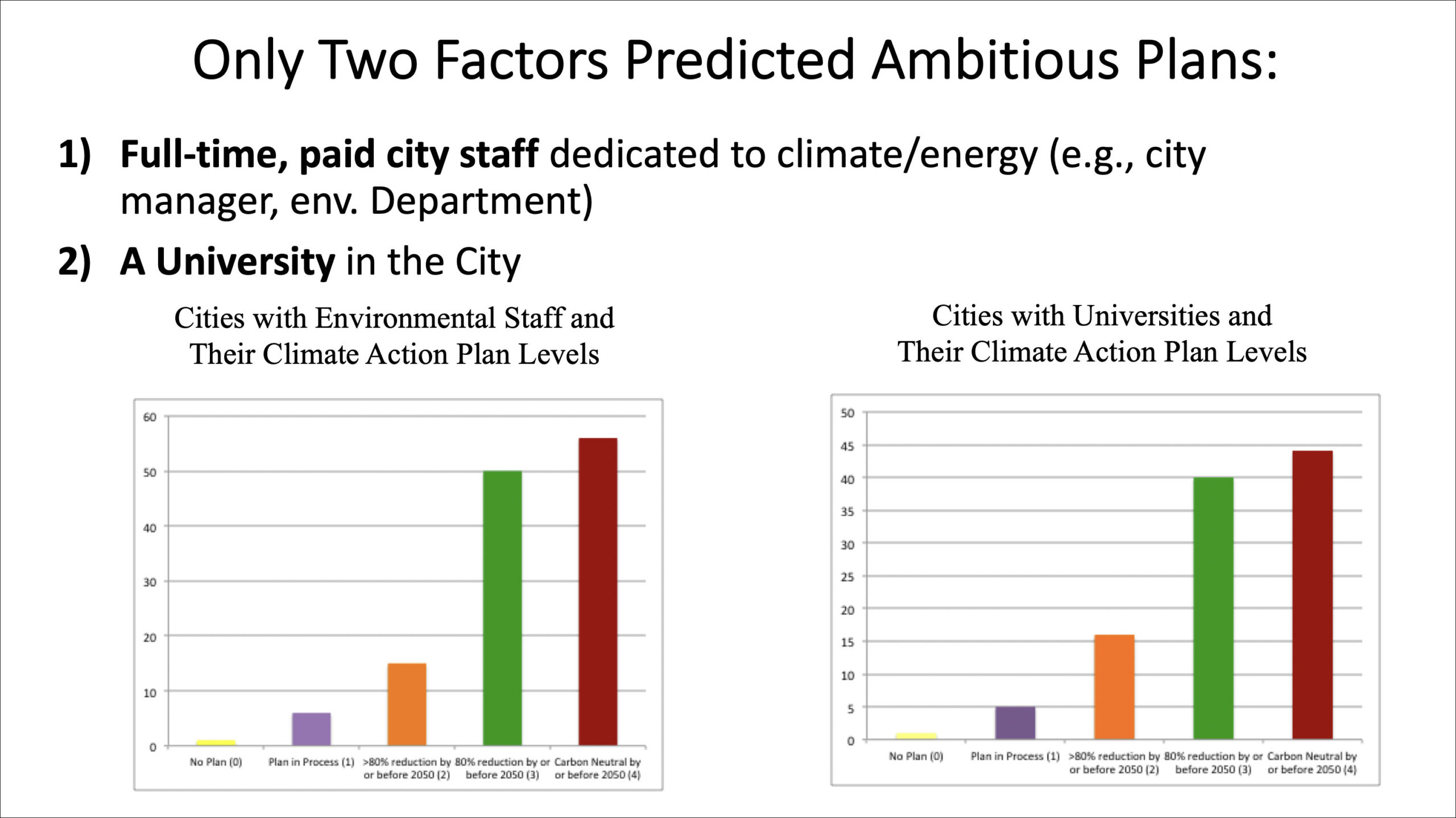

Cities with no plan and no apparent intention to create a climate action plan received a score of “1,” and cities that had a weak plan, with emission reduction targets of less than the IPCC’s recommended 80% by 2050, received a “2.” Plans that set a target of 80% reduction in emissions by 2050 were ranked as “3” and finally, if a city committed to achieving net-zero carbon dioxide emissions by or before 2050, they were given a “4” for being the most ambitious.

After collecting this data, Bery focused her study on what variables—if any—impacted what made a cities climate plan more ambitious.

Her findings? Ninety percent of the cities that had no climate-energy plans, also had no universities. In direct contrast, 61% of the cities that were the most ambitious, striving for carbon neutrality on or before 2050, had one or more four-year universities in their city. In addition, Bery discovered another leading factor was whether the city has a paid city employee (or department) dedicated to environmental/energy management.

“Other factors, such as per capita income, state funding, size, partisan orientation, and membership in international climate networks, commonly thought to influence a city’s interest and capacity for developing an ambitious climate action plan, did not significantly influence how ambitious a city’s climate action plan was,” Bery said.

In addition to the statistical analysis of the signatory cities, she made a qualitative study of Middletown, Conn. to explain why city energy managers and universities can have such a positive effect on city climate action.

Although Middletown is not a signatory city in the Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy, and wasn’t part of the data analysis, Bery says “by using the same definition of how we graded ambitiousness, Middletown would rank the highest because of their plan.”

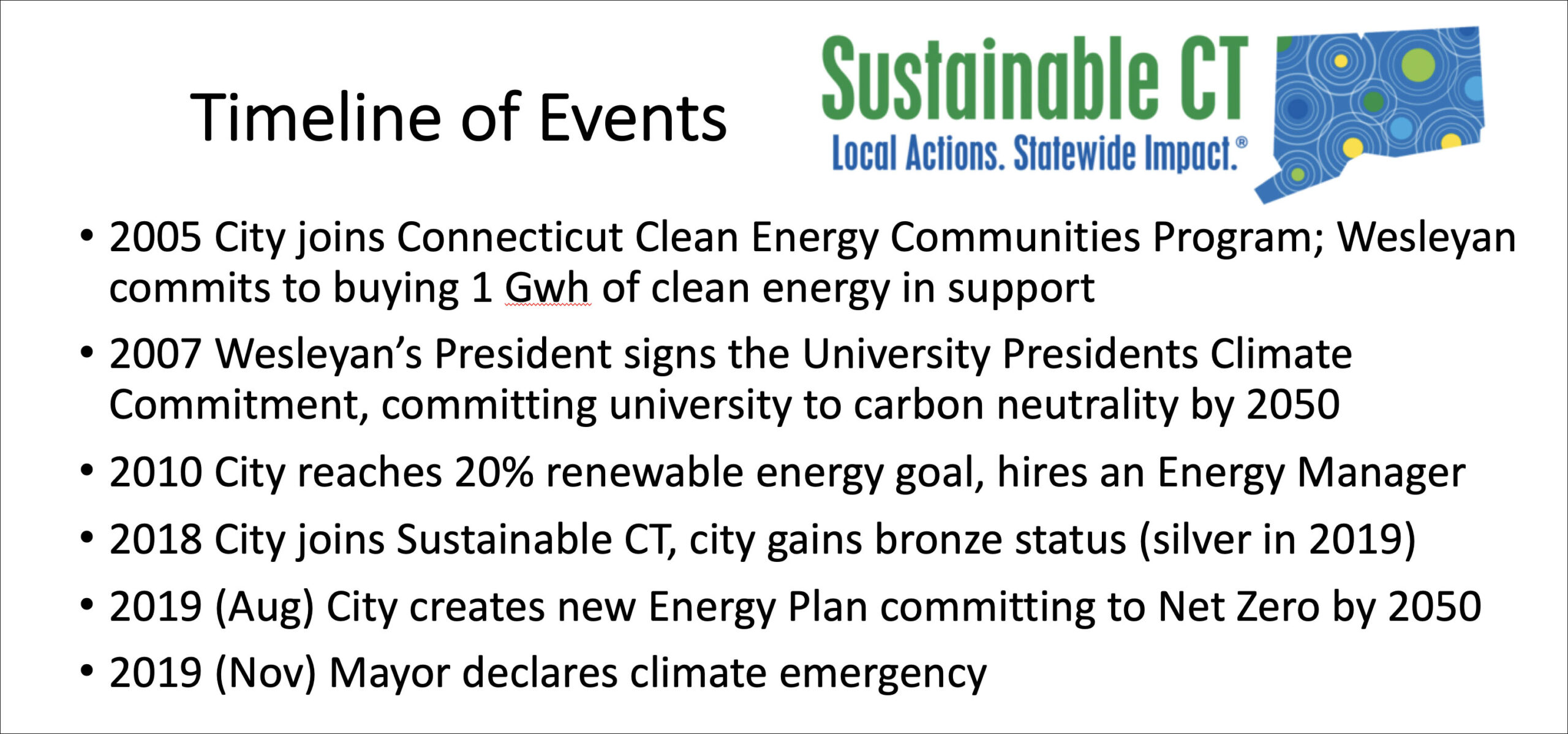

Bery first explored the history of both Wesleyan’s and Middletown’s environmental action plans. Middletown’s Energy Plan originated in 1980 with the published report titled “Energy in Middletown’s Future, A Preliminary Report to the Mayor and the Common Council.” Around the same time, Wesleyan began advocating for a recycling program.

In 2005, Middletown formed a Clean Energy Task Force, whose main mission was to help Middletown reach a 20 percent CO2 reduction target by 2010. Jennifer Kleindienst, Wesleyan’s sustainability director, currently chairs the CETF. In 2007, Wesleyan formed the Sustainability Advisory Group for Environmental Stewardship (SAGES), a committee of staff, faculty, and students that develops recommendations to the University community. And in 2010, President Michael Roth committed to Wesleyan being carbon-neutral (achieving net-zero carbon dioxide emissions) by 2025. That same year, Middletown hired a full-time energy coordinator, and in 2017, Middletown became the first municipality in the state of Connecticut to join Sustainable CT, which encourages strong and ambitious action in creating a carbon-free city by 2050.

Most recently, Kleindienst is revising Wesleyan’s Sustainability Action Plan, which expires this year, and is incorporating opportunities that lead to more collaboration and information sharing between Wesleyan and Middletown into the plan.

“Sanya’s study was quite extensive and thorough, and we were all grateful to her for her efforts,” Kleindienst said. “While I inhabit spaces in both Wesleyan and Middletown as a resident and local activist, I was surprised to learn that there are statistically viable significant and positive correlations between a municipality being home to a university and having an ambitious municipal energy plan.”

Bery initially became interested in climate activism through Sunrise Movement Middletown, a national movement propelled by young people across the country who want to end the corrupting influence of fossil fuel money in politics.

“I’ve been continuously inspired by the importance of the individual,” Bery said. “The large role that the University, its individuals, and the city it exists in can have on climate policy in a much larger capacity (say, beyond the university town, to the state, etc.). One inspired person, professor, university, town can cause really intense and crucial change.”