Senior Thesis: Peter Ketels Fulweiler ’23 Comments on AI and Surveillance with Sculpture

Art, like many areas of creative expression, does not always get the full attention it deserves. On average, visitors only spend 15 to 30 seconds looking at an artwork before moving on, according to studies done by several notable art museums.

Peter Ketels Fulweiler ’23 said hearing this statistic fascinated him and made him want to create art that kept people’s attention. He exhibited his senior thesis piece “Terms and Conditions,” an interactive sculpture, at the Ezra and Cecile Zilkha Gallery on March 28 to April 2.

And yet, 15 to 30 seconds would seem long for many to view something potentially much more personally risky—online terms and conditions. These decisions often seem like just another pop-up to glide past for users hungry to get to their favored social media site or a new app. The overwhelming majority of people click accept without ever reading what they agree to, according to a study by the Pew Research Center. Of the few who read them, only about 13 percent understand “a great deal” of what they are reading.

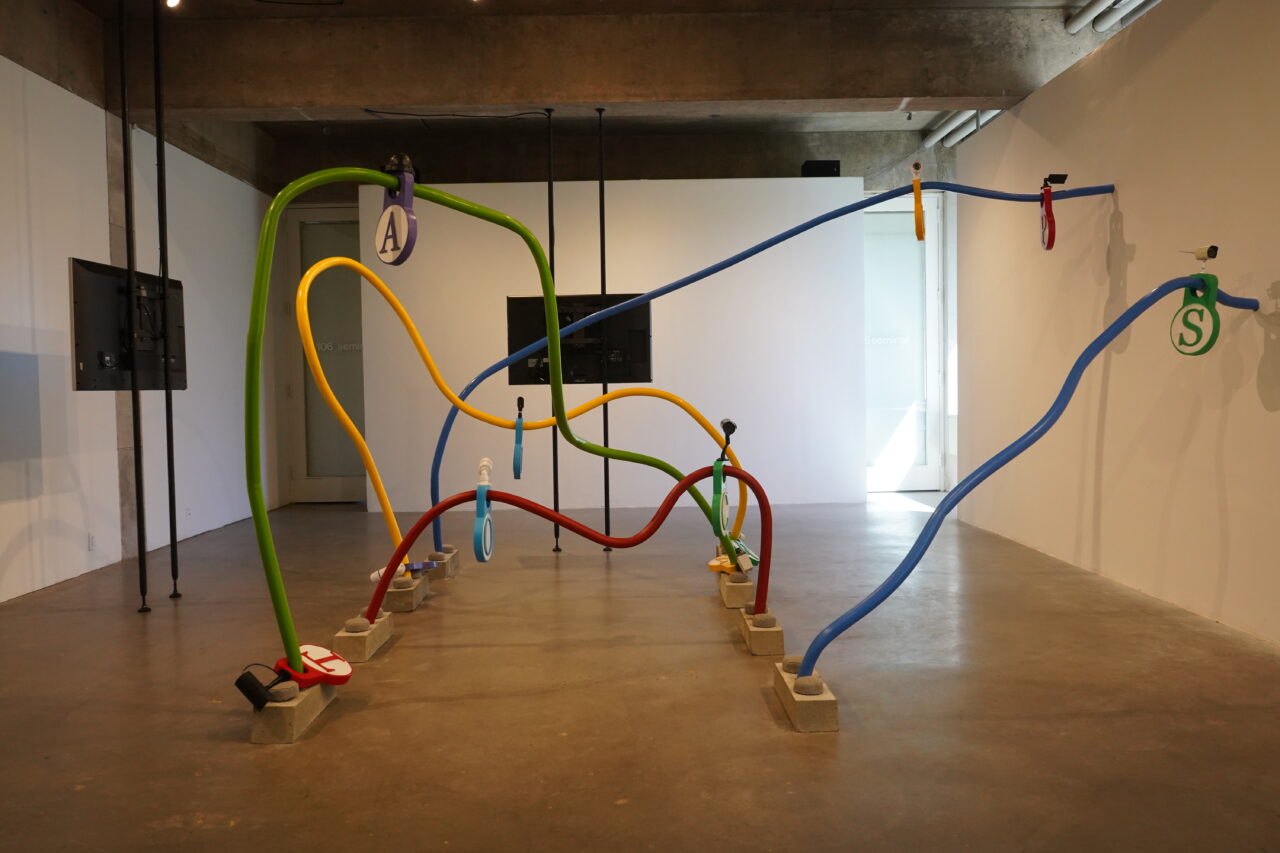

Fulweiler’s piece considered the questions surrounding privacy and surveillance. His sculpture was a large-scale play on a child’s toy popular in doctor’s offices and waiting rooms, a wire and bead maze, with attached security cameras and two connected monitors. The catch—only one of the security cameras was real and it was live-streaming to YouTube on a 30-second delay.

“I put a delay on the on the security cameras to the monitor so it would be really hard to tell which camera it was,” Fulweiler said. “In the same way as social media, where it’s really hard to tell what’s going on or how is the data being collected.”

After working with a playground designer this past summer, Fulweiler knew he wanted to incorporate some sort of interactive toy into the project. He said he wanted it to partially feel like a game, for visitors to find the real camera and interact with it.

“I want to build things that people interact with and things that people play with,” Fulweiler said. “I think that’s what I want to do with my life.”

He said many people took pictures of themselves posing in the camera once they figured out which one was real.

While researching ideas for his project, Fulweiler said he kept getting drawn to social media videos on TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube, which rely on algorithms that learn user preferences to keep their attention and advertise to them. It became clear to him he wanted to explore this social media reliance as he continued to return to these platforms.

“Why am I in this situation? Why are we in this situation?” Fulweiler said. “We’re just so addicted to our phones and social media.”

Fulweiler took responsibility for his own part in the loss of his data, in part, because he agreed to let these companies use his data to engineer a timeline for him. However, he was not sure how he agreed, or when.

“At some point I did agree for companies to take all my data and take it forever. And I never read (the terms and conditions.) I don’t feel like it was a total injustice, because that’s the law, and because I felt like it was kind of my own fault.”

After hearing from his peers during his critique, Fulweiler said he was satisfied with the end result, but wishes he did a better job about informing visitors about the livestream portion of the art piece. He made the livestream link private on YouTube, so it could not be viewed by the public.

“Other mechanisms of surveillance are much more insidious and scary,” Fulweiler said. He wanted viewers to draw their own conclusions from his work, but also consider their personal privacy decisions more carefully, he said.

Art is meant to push boundaries in a safe, thought-provoking way. Fulweiler’s piece did just that.