Raquel Bryant on Eight-Week Research Expedition in Waters of Greenland

A team of scientists from different corners of the field, all with unique backgrounds and countries they call home, tucked onto a vessel in the middle of the Northwest Atlantic for two months.

It could be the set up to a research-themed superhero movie, or the dream scenario for an early-career professor.

For Raquel Bryant, Assistant Professor of Earth and Environmental Sciences, getting this experience had been a bucket list item for the past decade. Bryant once had a research mentor who had a similar experience who told lively stories of the life at sea with some of the world’s most interesting and motivated researchers. This trip represents an opportunity for Bryant to grow as a researcher and learn from others.

“I think getting 30 international scientists together and having to work on something together is itself fascinating to me,” Bryant said. “I love seeing how people ask each other questions and challenge each other.”

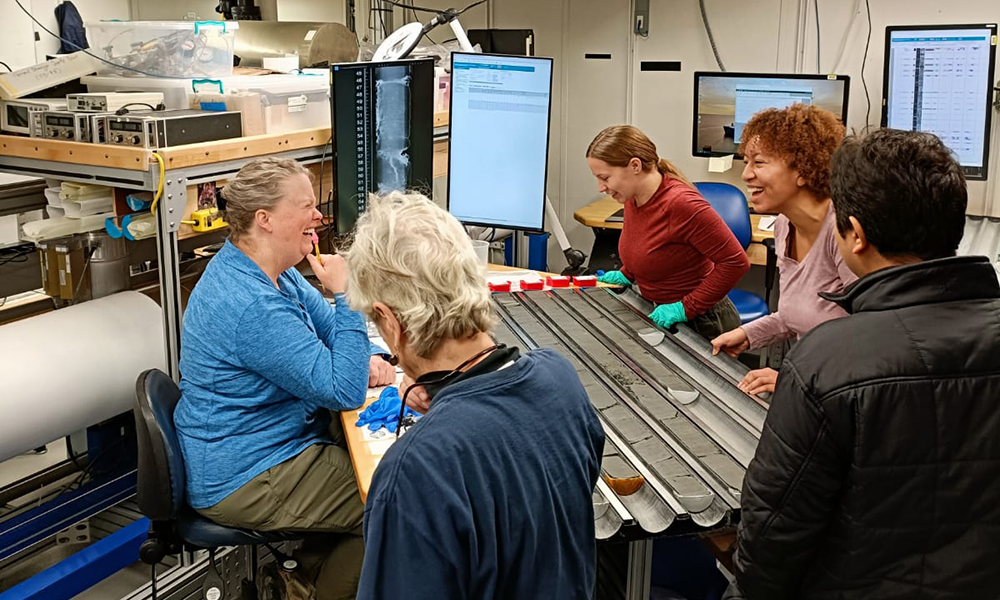

This semester the paleoceanographer and micropaleontologist set sail on the JOIDES Resolution with the International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) to study sediment cores from Baffin Bay, west of Greenland, to get a glimpse into how the Greenland Ice Sheet has evolved over time.

Bryant said that it is surprising that in recent decades the scientific ocean drilling community has done a significant amount of research into the Antarctic regions through numerous previous expeditions, but that this is the first time they are coring in the Arctic. A crucial goal of this expedition is to focus scientific minds on the Arctic to better understand this region and its history. Then once its history is better understood, scientists can better forecast how this region may react to future climate conditions.

“We need these geologic baselines to understand the development, the growth, and the behavior of the ice in the past to give other scientists the tools and the ground truth to then create their models and figure out what it might lead to it in the future,” Bryant said.

According to the IODP, the melting of the Greenland Ice Sheet could lead to a seven meter global sea level rise, which would result in significant damage to many of the coast lines where swaths of communities live.

Bryant spends her time on the boat on the initial processing of the cores in 30-to-90-minute cycles, on average, she said. When she’s not working with newly drilled cores, she’s often writing site reports. “I try to make writing central to what I do as a scientist, so that my students know that I think it’s important for science,” Bryant said.

This expedition is just the first step for the individuals involved, Bryant said. Once the at-sea period of core-collecting is over, there are still at least two years of follow-up research to go. Once Bryant gets back to Wesleyan, there is a whole other phase of in-depth, under the microscope core processing work.

Bryant will be examining microfossils for key indicators of both geologic age and environment to understand how the ice sheet changed over the last few million years. She is also studying how these microfossils change their size and shape in response to the onset of glaciation and proximity to the glacier, she said. Bryant has largely focused on the Cretaceous period, about 100 million years ago, in her research to this point. This study looks at a period from about one to 20 million years ago, a vastly different climate and structure than what she is used to. This period gives students a closer look at modern climate change, though, which could be a key factor in many of their future considerations, she said.

Another factor in Bryant’s decision to pursue this journey was that it would give undergraduates an opportunity to assist her in this next phase of research.

“I wanted to work on this project to give my students something a little more tangible to be involved with, and I know everybody is fascinated by the Arctic and how quickly it’s changing in response to this new climate state that we’re in,” Bryant said.