Discovery by Chernoff and Students Challenges a Tenet of Evolutionary Biology

As organisms evolve over time, changes in size—both miniaturization and gigantism—are a major theme. In fish, which are the specialty of Barry Chernoff, the Robert Schumann Professor of Environmental Studies, Professor of Biology and of Earth & Environmental Sciences, miniaturization happens in many lineages, though it’s not very common. Evolutionary biology has long held that this miniaturization is often accompanied by developmental simplification or paedomorphisis (becoming sexually mature while appearing juvenile-like).

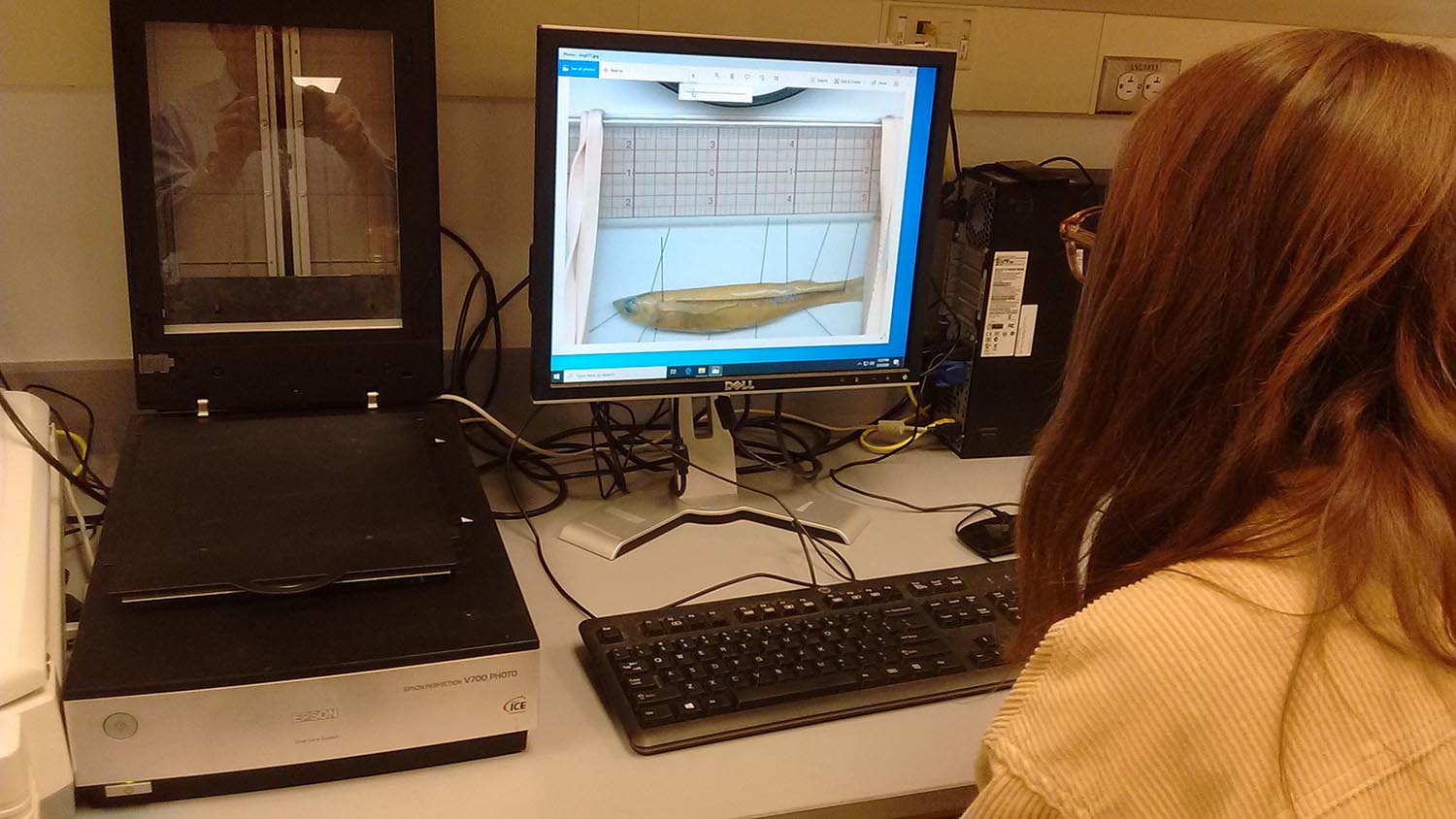

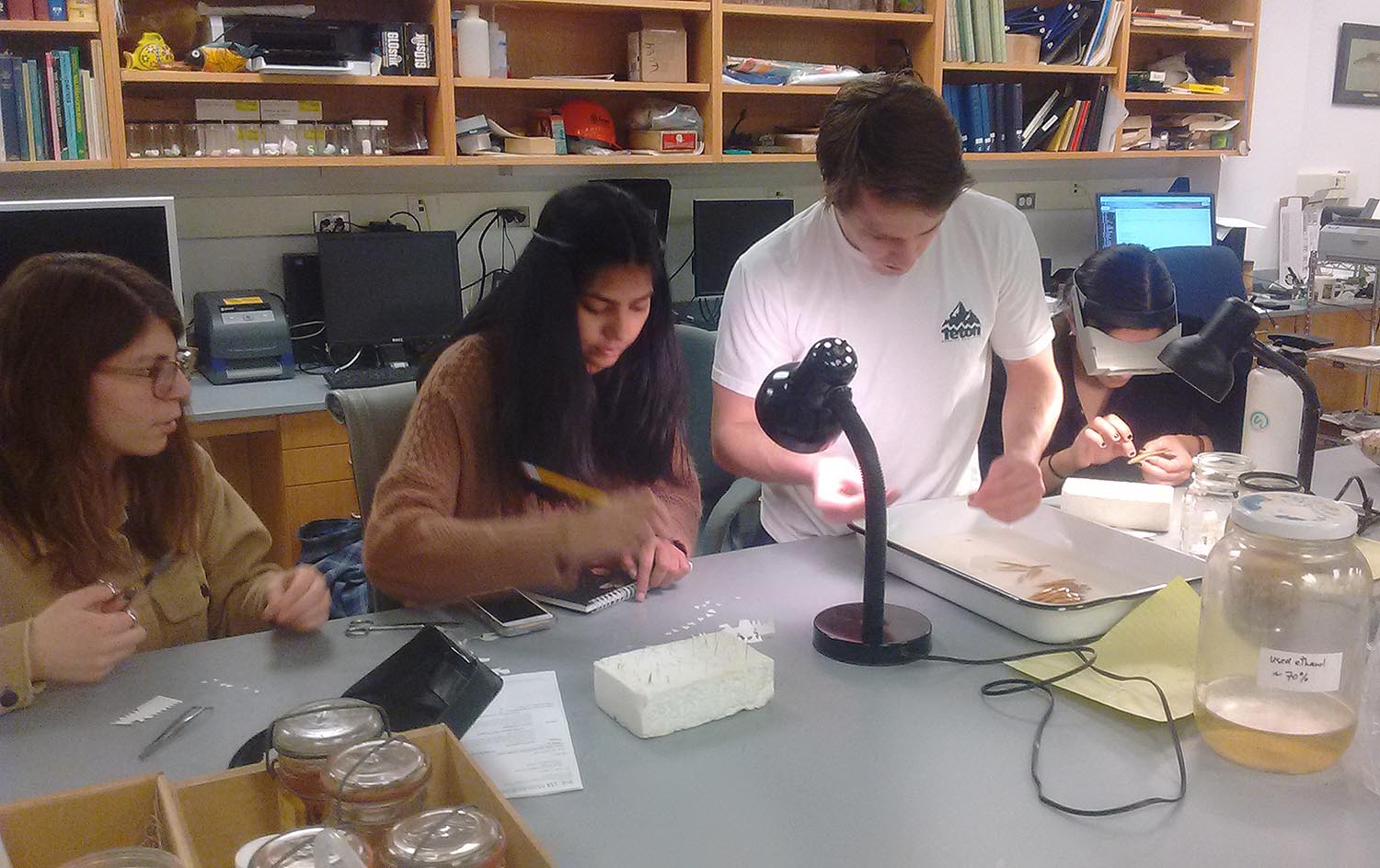

Last March, just before the pandemic began, Chernoff and students in his Tropical Ecology course (ENVS/Bio/E&ES 306) took a trip to the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Mich., which is home to one of the largest scientific collections of natural history objects, or specimens, and allows visitors to work with their collections. There, they discovered two new species of fish from the tropics—one from Honduras and one from Colombia. In these new species, the data demonstrated the opposite of expectations from evolutionary theory: that miniaturization occurred with developmental acceleration. That is, the miniatures achieve adult morphology in a shorter period of time by accelerating the transformation from juvenile morphologies to adult morphologies.

Last March, just before the pandemic began, Chernoff and students in his Tropical Ecology course (ENVS/Bio/E&ES 306) took a trip to the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Mich., which is home to one of the largest scientific collections of natural history objects, or specimens, and allows visitors to work with their collections. There, they discovered two new species of fish from the tropics—one from Honduras and one from Colombia. In these new species, the data demonstrated the opposite of expectations from evolutionary theory: that miniaturization occurred with developmental acceleration. That is, the miniatures achieve adult morphology in a shorter period of time by accelerating the transformation from juvenile morphologies to adult morphologies.

Chernoff and his colleague and students have published their findings in ZOOTAXA, the top-ranked journal for species new to science and systemic revisions, edited by a curator of fishes at the American Museum of Natural History. The co-authors are Antonio Machado-Allison, research fellow in the College of the Environment, Jennifer Escobedo ’20, Michael Freiburger ’21, Elijah Henderson ’23, Andrew Hennessy ’21, Grace Kohn ’22, grad student Nola Neri, Aashni Parikh ’22, Sophie Scobell ’22, Benjamin Silverstone ’22, and Emily Young ’22.

Chernoff is also chair of the Environmental Studies Program and director of the College of the Environment.

Chernoff explained that scientists believe there may be multiple evolutionary purposes for miniaturization, each specific to a species or lineage of species. Some possible reasons include that miniaturization allows organisms to fit into smaller habitats, to feed on smaller-sized prey, to avoid predation (i.e., being smaller may be energetically less interesting to predators), and to become fertile and reproductive more quickly, though the number of potential offspring will be reduced.

Miniaturization is commonly understood to occur through paedomorphosis, which is when the juvenile form of an animal develops the ability to reproduce at a much smaller size and at an earlier age. In this case, the miniature looks similar to the juvenile or even larval forms of normal-sized species.

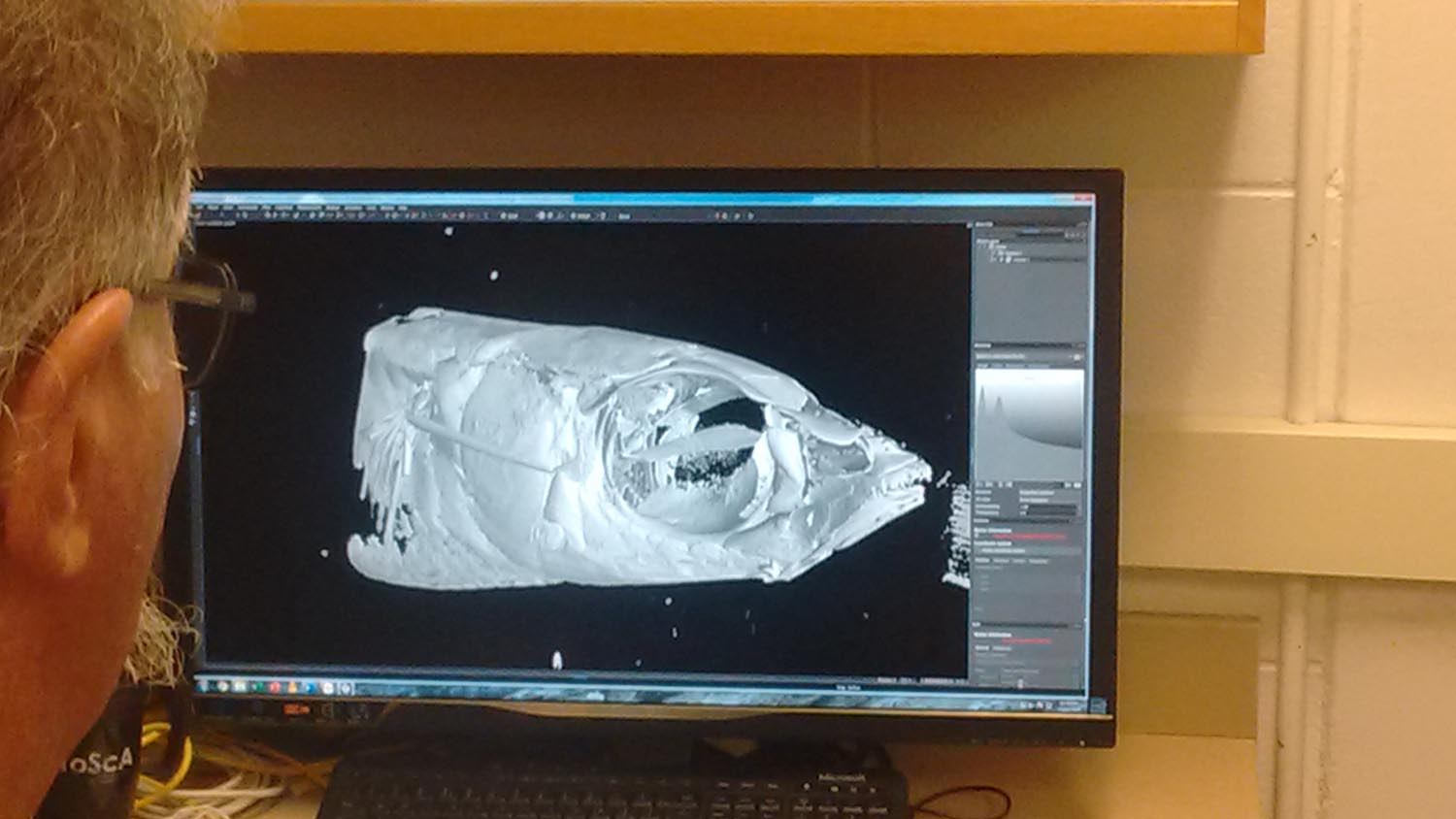

Another way that miniaturization occurs, which has only been reported a few times in the past, is when the species becomes fertile at a small size but it has the morphology of adults of normal-sized species. This occurs by speeding up the transformation of all the internal systems, including the reproductive organs. Thus, the miniatures mature at smaller sizes and look like tiny adults.

To illustrate, Chernoff said, “Imagine if we took a photo of you as a baby and a photo of you now. Let’s shrink your image in the adult photo to the size of you as a toddler. We would have no problem identifying the toddler you from the adult you. Babies and juveniles have different body proportions than adults—just think about what makes babies cute: they have very large eyes compared to the size of their heads, better known as the ‘Bambi effect.’ Now, let’s consider your adult image at the size of a toddler—you have the adult body shapes and lengths (head size, arm lengths, etc.). So if you had those shapes at the size of a toddler, then your system would have had to accelerate the development of all the parts relative to you getting taller.”

Chernoff first published on this effect in a book he co-authored in 1985. The new species he and his students discovered provide an important test of how size change is accomplished during the evolutionary history of lineages of organisms. Chernoff believes these results can be general and will be discovered in other species. The publication by Chernoff and his students is also important because it adds to our knowledge of biodiversity of coastal habitats in the New World tropics.

Additional photos are below: