Center for the Study of Guns and Society Delves into the Links Between Firearms and Domestic Violence

Every month in the US, roughly 70 women are shot and killed by their partners. Yet in February 2023, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals overturned a 1994 law banning firearms possession for people subject to domestic violence protection orders, part of a wave of lower-court challenges to gun regulations following the Supreme Court’s pivotal 2022 decision in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen.

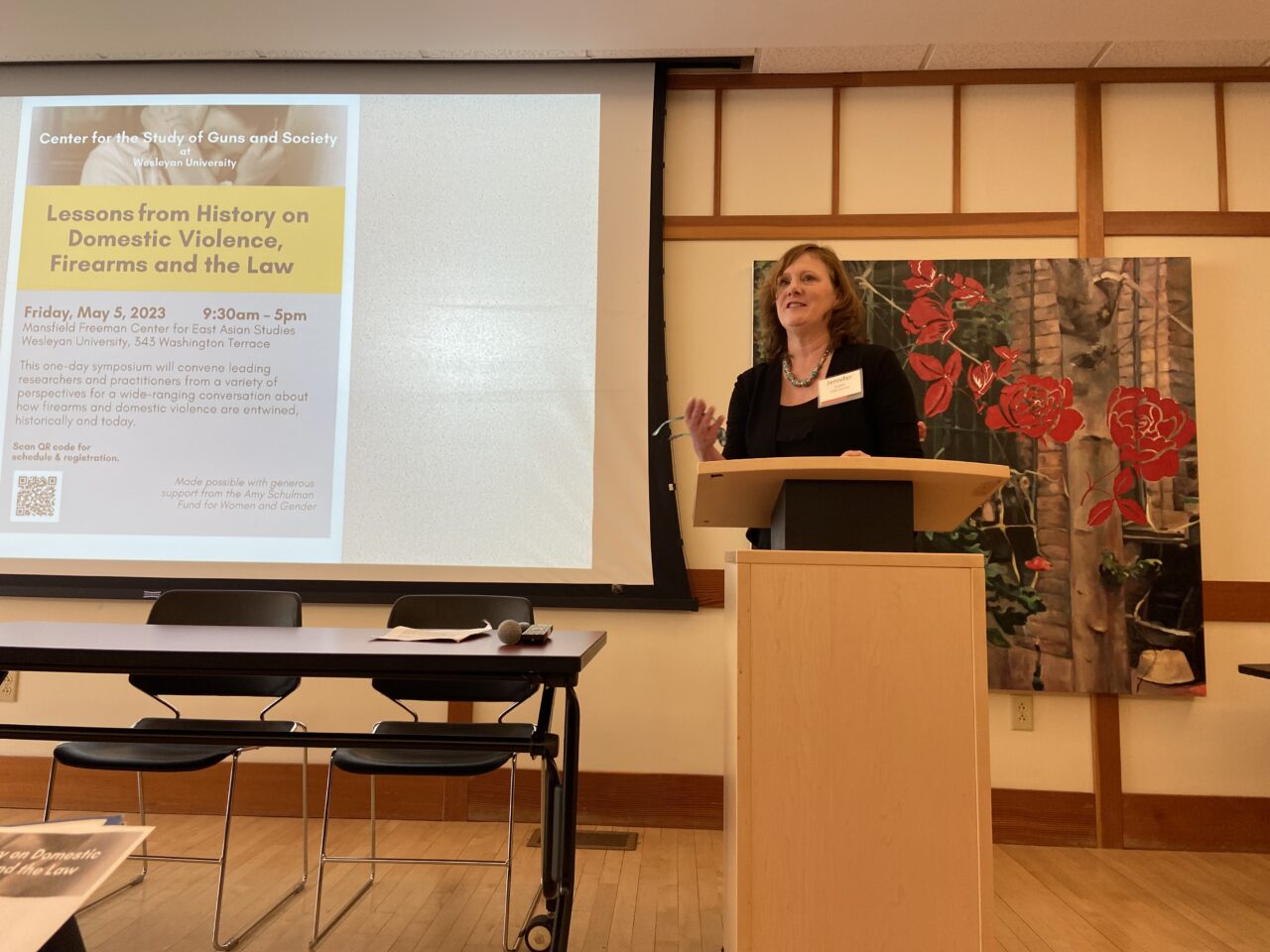

With that background, the Center for the Study of Guns and Society at Wesleyan convened historians, legal scholars, and gun violence prevention experts for a symposium, “Lessons from History on Domestic Violence, Firearms, and the Law,” on May 5. The Center’s third event since its founding last year, made possible through a generous grant from the Amy Schulman Fund for Women and Gender, offered sobering insights into how guns impact intimate partner violence, reproductive justice, and beyond.

“The symposium convened leading researchers and practitioners from a variety of perspectives for a wide-ranging conversation about how firearms and domestic violence are entwined, historically and today,” said Jennifer Tucker, associate professor of history and the Center’s founding director. “The speakers presented findings from the latest legal, historical, public health, and policy research as well as discussed the implications of the Court’s decision for the domestic violence crisis, and how the proliferation of guns in US homes affects historical patterns of domestic (physical, sexual, and psychological) abuse.”

The Fifth Circuit Court’s ruling in United States v. Rahimi, which overturned the 1994 law known as the “domestic violence prohibitor,” follows a watershed standard the Supreme Court set in Bruen: Firearms regulations must be analogous to similar laws from early American history. But as more than one conference presenter noted, relying on a historical record overwhelmingly authored by white males is inherently problematic.

“This idea that the Second Amendment is fixed according to the historical understanding—and therefore you can’t find evidence of laws regarding domestic abuse and the like—is ridiculous,” Kelly Sampson, senior counsel and director of racial justice at The Brady Center, said in the opening session. “There’s no reason why, in 2023, our gun laws should be tied to a time where women or people of color were not part of the legislatures—they weren’t even considered people.” (Listen to Tucker’s recent podcast interview with Sampson, in which they discuss the importance of studying history in approaching America’s crisis of gun violence.)

Washington Post columnist Karen Attiah moderated a panel on the overlaps between gun safety and reproductive rights. In the US, states with the strictest abortion laws have adopted some of the weakest gun regulation and homicide is a leading cause of death for people who are pregnant or have recently given birth, with firearms involved in most incidents. “We have to think about gun control as not just about bad people having guns, but what it means to grow up in a culture where guns are what is in your household,” said Crystal Feimster, a Yale historian specializing in 19th– and 20th-century African American history and women’s history. “And that comes at a really high cost, particular in households where there is violence.”

Throughout the day, discussions covered subjects ranging from epidemiology and law to the need for public policy on gun violence prevention measures. The symposium also included presentations by eminent historians Laura Edwards (Princeton University) and Elizabeth Pleck (University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign) on the historical record of domestic violence and women’s rights from the 1700s to today, including how women advocated for themselves centuries ago in ways that are being overlooked by the contemporary judiciary in their analogous thinking. Jacquelyn Campbell (Johns Hopkins School of Nursing), a national leader in research and advocacy in the field of domestic and intimate partner violence, and Matthew Miller, a physician and professor of health sciences and epidemiology at Northeastern University and co-director of the Harvard Injury Control Research Center, presented data showing dramatic increases in the risk of death by suicide or homicide when a domestic partner becomes a lawful gun owner.

In another session, Victoria Nourse, the Ralph V. Whitworth Professor of Law at Georgetown University and a member of the US Commission on Civil Rights, spoke about the broad implications of originalism, the legal theory driving Bruen as well as the overturning of Roe v. Wade. “The point [of originalism] is not restraint—that’s gaslighting,” said Nourse, who assisted in passing the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act and the original Violence Against Women Act. “It is power. It is judicial activism.”

Despite the breadth of Bruen, Reva Siegel, Yale Law School professor of constitutional law, offered a sense of how legal professionals might argue about its meaning. “The bottom line here is that the Fifth Circuit court is hiding behind the analogical method to make distinctions that are not impelled by Bruen,” Siegel said. “There is room to work inside of the opinion as well as to criticize it.”

The struggles around gun rights and regulations continue to play out in a post-Bruen world. Saul Cornell, a Fordham University law and history professor specializing in early American constitutional thought, said that it’s vital that trained historians have a seat at the table. “History has the power to enlighten us, and I hope conferences like this will help us do that.”

Visit the Center for the Study of Guns and Society for more information and updates on future events.