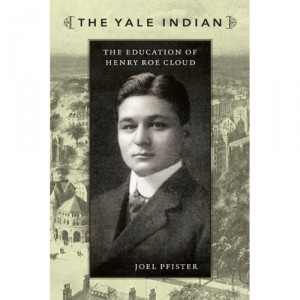

Pfister’s The Yale Indian Profiles Roe Cloud

American history has almost completely edited out Henry Roe Cloud from its story, even though this full-blood Winnebago was one of the most accomplished and celebrated American Indians in the first half of the twentieth century. Joel Pfister’s The Yale Indian: The Education of Henry Roe Cloud corrects this omission.

Pfister, chair of the English Department and the Kenan Professor of the Humanities, and former chair of the American Studies Program, began exploring American Indian archives when he was a Yale doctoral student in the 1980s and started his research on Yale’s Roe Cloud letters in 1995. Very little has been published about the experiences of the few American Indians who beat tremendous odds to make it to college in the early 1900s. Pfister aimed to find out more about the undergraduate years of one of the most inspiring advocates of higher education for Native Americans.

Next year marks the 100th anniversary of Roe Cloud’s graduation from Yale College in 1910. His portrait does not hang in Yale’s Sterling Memorial Library, near that of Edward Alexander Bouchet (the first African American to graduate from Yale), but Pfister thinks it should.

Roe Cloud was the first Native American to graduate from Yale. He was an extremely successful and popular student and alumnus. After college he attended Oberlin Seminary, received a divinity degree from Auburn Theological Seminary in 1912, and two years later was the first Indian to earn a Yale graduate degree, an M.A. in anthropology. Before arriving in Connecticut, Roe Cloud lived on the Winnebago Reservation in Nebraska and attended the mission-run Santee Normal Training School and later the innovative Mount Hermon School in Northfield, Massachusetts.

His middle name comes from two missionaries, Mary Wickham Roe and her husband, Reverend Dr. Walter C. Roe. They informally adopted him not long after he matriculated at Yale. Roe Cloud was elected to the newly founded Elihu Club, a prestigious secret society that was rigorously intellectual in focus. According to Pfister, Roe Cloud was “a great orator” and debater who “waged battle with the ruling class” elite by winning them over with his grace and intelligence. He consistently spoke out about the need to improve schooling for Native Americans and, when he was an undergraduate, proposed that Yale found a prep school for Indians.

“Roe Cloud was the most successful Indian fundraiser of his day,” Pfister points out. He learned to convert wealthy white college students and their social circle into allies. While he educated those in power about the need for expanding educational access, he steadfastly maintained contact with the people he fought for, even during his college years.

While Roe Cloud had to negotiate discrimination in different settings beyond Yale, his letters do not mention Indian stereotypes that he had to have encountered on campus. Although he was at the school during a time when elites wanted to “Americanize” the American Indian, there were Yale organizations called the Mohegan Club (Yalies caroused in Indian costumes) and the Wigwam Club (a debate team) that caricatured rather than honored Native Americans. One summer when Roe Cloud sold books door-to-door in Connecticut, he was disappointed to find that he was frequently asked more about Indian arrowheads than about his books. In fact, the erudite and eloquent Roe Cloud was more educated than most of his customers. He knew German, Greek, and Latin, as well as Sioux and Winnebago.

He did not want to give “oppression more power that it already had over him,” as Pfister put it, so he refrained from allowing what he was up against to wholly define him and his game plan.

“He used Yale as a class passport to make things happen,” Pfister notes, and did all he could to improve the life chances of Indians.

The book is not a complete biography of Roe Cloud, but its focus on Roe Cloud’s ongoing forms of higher education considers the lessons that Roe Cloud still offers readers interested in bringing about progressive social change. Roe Cloud’s thinking resonates with W. E. B. Du Bois’s call for the establishment of a “talented tenth” of African Americans in 1903. Roe Cloud’s advocacy of education in effect supported the formation of an Indian “talented tenth” who would have a shot at entering the halls of power as advocates.

Roe Cloud was the only Indian coauthor of the hugely influential Brookings Institute’s Meriam Report in 1928. This study paved the way for major policy reforms in the Indian New Deal. One of his letters to John Collier, the New Deal’s controversial head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, suggests that it was Roe Cloud, perhaps even more than Collier, who originated some key ideas that led to the Indian Reorganization Act, the legislation that structured the Indian New Deal.

Roe Cloud was an early developer of Indian white-collar activism. The strategies that he used to advance his goals remain relevant for Indians and others to learn from today. “The problem [of access to higher education for Indians] that Henry Roe Cloud dedicated his life to addressing,” Pfister observed, “is still with us.”