O’Connell in The Conversation: How Deep is the Ocean?

Wesleyan faculty frequently publish articles based on their scholarship in The Conversation US, a nonprofit news organization with the tagline “Academic rigor, journalistic flair.” Professor of Earth and Environmental Sciences Suzanne O’Connell has written a new article for The Conversation’s “Curious Kids” series answering the question “How deep is the ocean?” The article is based on her research studying the sea floor.

Curious Kids: How deep is the ocean?

Explorers started making navigation charts showing how wide the ocean was more than 500 years ago. But it’s much harder to calculate how deep it is.

If you wanted to measure the depth of a pool or lake, you could tie a weight to a string, lower it to the bottom, then pull it up and measure the wet part of the string. In the ocean you would need a rope thousands of feet long.

In 1872 the HMS Challenger, a British Navy ship, set sail to learn about the ocean, including its depth. It carried 181 miles (291 kilometers) of rope.

During their four-year voyage, the Challenger crew collected samples of rocks, mud and animals from many different areas of the ocean. They also found one of the deepest zones, in the western Pacific, the Mariana Trench, which stretches for 1,580 miles (2,540 kilometers).

Today scientists know that on average the ocean is 2.3 miles (3.7 kilometers) deep, but many parts are much shallower or deeper. To measure depth they use sonar, which stands for Sound Navigation And Ranging. A ship sends out pulses of sound energy and measures depth based on how quickly the sound travels back.

The deepest parts of the ocean are trenches – long, narrow depressions, like a trench in the ground, but much bigger. The HMS Challenger sampled one of these zones at the southern end of the Mariana Trench, which might be the deepest point in the ocean. Known as the Challenger Deep, it is 35,768 to 36,037 feet deep – almost 7 miles (11 kilometers).

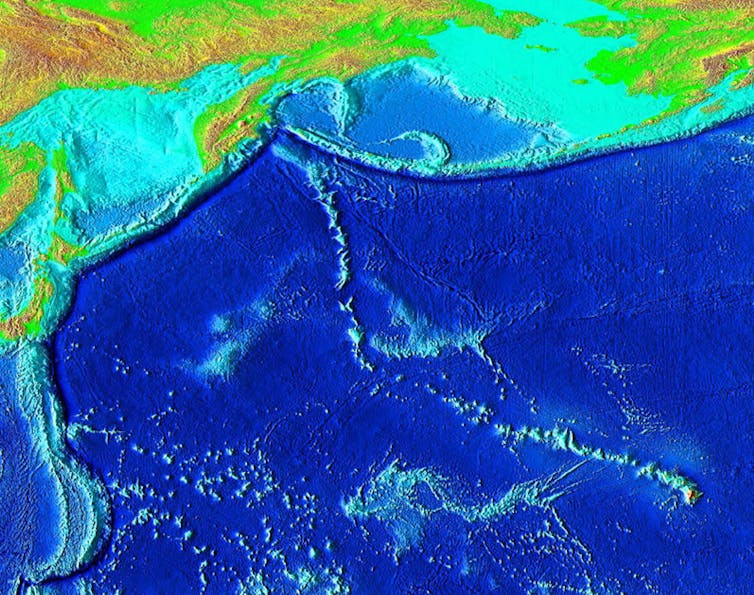

Ocean scientists like me study the sea floor because it helps us understand how Earth functions. For example, our planet’s outer layer is made of tectonic plates – huge moving slabs of rock and sediment. The Hawaiian-Emperor Seamount chain, a line of peaks on the ocean floor, was created when a tectonic plate moved over a spot where hot rock welled up from deep inside the Earth.

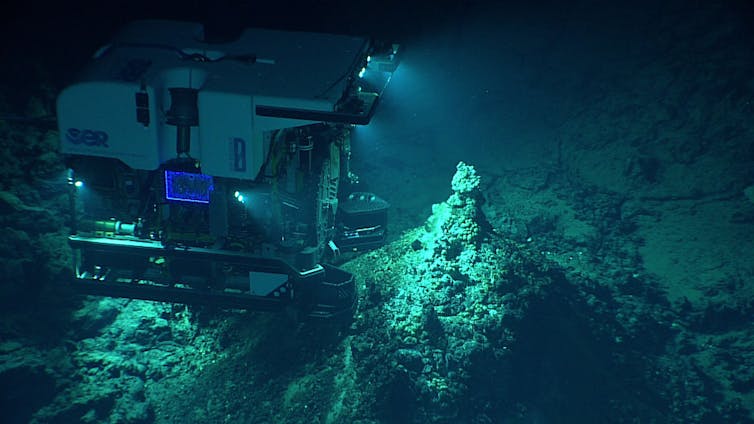

When two tectonic plates move away from each other underwater, new material rises up into Earth’s crust. This process, which creates new ocean floor, is called seafloor spreading. Sometimes super-hot fluids from inside the Earth shoot up through cracks in the ocean floor called hydrothermal vents.

Amazing fish, shellfish, tube worms and other life forms live in these zones. Between the creation and destruction of ocean plates, sediments collect on the sea floor and provide an archive of Earth’s history, the evolution of climate and life that is available nowhere else.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.