Battle for the Future: Smolkin-Rothrock on the Spiritual Life of Soviet Atheism

(Story contributed by Jim H. Smith)

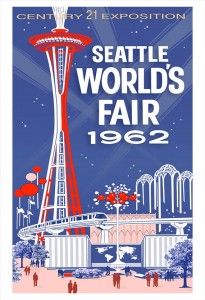

Its official name was the Century 21 Exhibition, but it was better known as the Seattle World Fair, and it seemed to be an unambiguous statement about America’s aspirations for its future. Boasting a futuristic monorail and an iconic Space Needle whose elevators were piloted by female attendants wearing excessive blue eye shadow and costumes out of a Hollywood sci-fi feature, it came to hold totemic significance for a nation whose philosophical differences with the Soviet Union were being sorted out against the majestic backdrop of outer space.

One of the first visitors to the 1962 fair was Soviet cosmonaut German Titov, the second Soviet man in space after Yuri Gagarin, the youngest spaceman (a record that stands to this day), and the first to orbit the Earth repeatedly. In his homeland Titov was nothing less than a demi-God.

During a news conference in Seattle, Titov was asked whether his adventures in the cosmos had altered his worldview. “Up to our first orbital flight by Yuri Gagarin no God helped build our rocket,” said the cosmonaut, who perceived the subtext of the question. “The rocket was made by our people. I don’t believe in God. I believe in man, his strength, his possibilities and his reason.”

It was, says Victoria Smolkin-Rothrock, assistant professor of history, assistant professor of Russian and Eastern European studies, a statement that bespoke the essence of the Soviet Union’s long, strange struggle to supplant traditional religions throughout the empire with “scientific atheism.” If it provoked an outcry across America, well, that was Titov’s intent.

During the 1960s, as Smolkin-Rothrock notes, Titov and his fellow cosmonauts “were the public face of Communism on the world stage, and their triumphs and charisma put forward a confident image of a Communist state that could solve all problems and answer all questions, material and spiritual.”

On Oct. 18, Smolkin-Rothrock delivered this year’s prestigious Sherman Emerging Scholar Lecture at the University of North Carolina-Wilmington. Her address, which began with the Titov story, offered an analysis of Communism’s little-known efforts to manage the collective spiritual life of the Soviet people.

A native of Ukraine – where she lived until she was eight, when her family emigrated to America – Smolkin-Rothrock has carved out a special research niche, succinctly summarized in the title of her lecture, “A Sacred Space: The Spiritual Life of Soviet Atheism.” The title is drawn from a Russian proverb: a sacred space is never empty. That, in turn, is the title of the doctoral dissertation she wrote at the University of California-Berkeley, where she did much of her research on the Soviet state’s efforts to manage the nation’s spiritual life with atheist beliefs and practices, especially as these efforts intensified during the last half of the 20th century. And it will be the title of her forthcoming book, subtitled Scientific Atheism, Socialist Rituals and the Soviet Way of Life, 1954-1991.

“I read a number of books that offered various interpretations of the story of the official state ‘religion’ in the Soviet Union,” she says, “but they didn’t conform with what I knew from personal experience.” One of the questions that has driven her research is how a state that has been described as totalitarian left the most important questions about the meaning of human life and death unaddressed for so long.

The Bolshevik Revolution ignited a confrontation between the new ethos of scientific atheism and the traditional religions practiced by the various peoples residing in the states subsumed by the Soviet Union, but Smolkin-Rothrock says the government’s efforts to convert the population and transform religious beliefs into atheist cosmologies were never a resounding success. In the early years of the Soviet state, atheist propaganda often relied upon strong-arm intimidation. Later, in the post-World War II period on which her research primarily focuses, more subtle forms of persuasion became the order of the day. “Khrushchev had a saying,” she notes. “‘You can’t beat people into Paradise with a club.’”

Cosmonauts were chief among Soviet propaganda symbols, but the ideological confidence their image was meant to portray was a thin veneer, masking a fundamental crisis in the state’s ideological agenda, she notes. To illustrate the point, she relates an incident that occurred six years before Titov’s visit to Seattle. Prominent writer Alexei Surkov, head of the Writer’s Union, had received a letter from a Russian woman who asked the Party and Soviet writers to produce replacement rituals for the religious rites marginalized by the Soviet Union’s war on religion. However, when he notified the Party Central Community about this remarkable observation, he was told that creating and disseminating new socialist rituals was outside the purview of the government.

“The exchange provides a window into the story of how the Soviet state struggled to fill the ‘sacred space’ made empty by the war against religion,” says Smolkin-Rothrock. “The state became the only place that recorded births, marriages and deaths, and for a long time recording them, in an austere government office, was all the state offered to replace religious rituals. However, what Soviet atheists came to believe was that any ideology must be able to add meaning to these critical rites of passage, even if it is an ideology that disavows the existence of God.”

Eventually, by the time Leonid Brezhnev replaced Nikita Khrushchev in 1964, “the Soviet leadership had mobilized unprecedented resources and expertise to transform the Soviet cosmos,” she says. “Atheism went from being a neglected component of the regime’s ideological program to the center of intensive debate about the place of religion within socialist modernity, and the state’s role in Soviet spiritual affairs.”

She adds that “Generally, the story is about the regime’s repressive campaign against religious institutions and believers, what can be described as the ‘negative’ component of secularization, whereas it seems to me that examining the positive program of the state is, in fact, much more revealing both of what the Soviet state was, and of what it wanted to become.”

She is quick to point out that the Soviet Union was not unique in its increasingly effective use of propagandist imagery to deliver messages to its constituents. The World’s Fair, she notes, was a product of the “escalating tension in the culture war between science and religion.” It was “originally conceived as a mechanism to raise the public esteem for science in light of the fact that, as John W. Campbell, the editor of Astounding Science-Fiction, put it, ‘The American people have been thoroughly scared witless by the accomplishments of science’ – by the atomic bomb, by Sputnik, and by the prospect of actual Soviets transgressing the heavens and invading the American skies.”

Hence the World Fair became an ideological battleground where, at the dawn of the 1960s, the meanings of atheism, science and religion were contested. By the time the fair ended, the same month as the Cuban missile crisis, it had attracted more than 10 million visitors. Many of them would never think of the future in the same way again.