Hickenlooper ’74 Releases Engaging Memoir

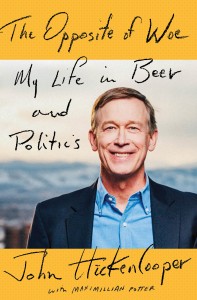

Irrepressibly optimistic, funny, self-deprecating, at times self-doubting but driven to tackle difficult challenges. These are the qualities that shine through in John Hickenlooper ’74’s disarming autobiography, The Opposite of Woe: My Life in Beer and Politics (with Maximillan Potter; Penguin Press, 2016).

Irrepressibly optimistic, funny, self-deprecating, at times self-doubting but driven to tackle difficult challenges. These are the qualities that shine through in John Hickenlooper ’74’s disarming autobiography, The Opposite of Woe: My Life in Beer and Politics (with Maximillan Potter; Penguin Press, 2016).

It was in a moment of self-doubt, or perhaps profound personal insight, that Hickenlooper chose Wesleyan over Princeton, having been accepted to both universities in 1970. He confesses now that he didn’t think he was good enough for Princeton, but then adds, “I had a feeling that Princeton would be a bit too conservative, too buzz-cut and buttoned-down for me, and that Wesu’s long-haired liberal arts types would be more my crowd.” He was right.

Hickenlooper’s time at Wesleyan was remarkable for its longevity, and he devotes three chapters to “That Decade I Spent in College.” With candor unlike any politician bent on image burnishing, he tells in detail how he had his heart broken in love. An English major, he discovered his interest in geology in the second semester of his senior year, when he attended a lecture with a friend and found himself captivated by a discussion of leach fields and perc tests. He stayed at Wesleyan as a special student to take courses specified by the Geology Department as a prerequisite to being admitted into the master’s degree program, which he received in 1980.

When Hickenlooper’s first career as an oil geologist crashed in the 1980s oil bust, he turned his attention from black gold to golden ale, establishing Wynkoop Brewing Company, Denver’s first microbrewery, in the city’s then run-down LoDo area. Although the thought of holding public office hadn’t crossed his mind, beer brewing turned out to be a perfect launching pad to a political career.

Wynkoop gave Hickenlooper—a consummate people person—a connection to the community and helped him gain a solid understanding of the needs of small business owners, providing an outlet for his natural desire to work with others to get things done. With investors skeptical and in short supply, Hickenlooper’s gamble on Wynkoop was risky but prescient: Microbreweries took off, Wynkoop prospered, and Hickenlooper’s reputation as an adventurous businessman began to grow.

In 2001 controversy erupted over a plan to sell the naming rights for Denver’s new stadium, replacing the historic Mile High Stadium, home of the Broncos. Denver’s mayor enlisted Hickenlooper’s support in fighting the effort. The “skinny restaurateur,” as Sports Illustrated called him, found himself in front of banks of television cameras: the citizen-leader of a successful fight to retain “Mile High” as part of the name.

To say it was an easy road from there to the mayor’s office would do an injustice to the book’s riveting account of how Hickenlooper turned a long-shot bid into a win. His unconventional television ads are a case in point. In one, he is shown trying on a western shirt and cowboy hat in a clothing store, saying: “Everybody says I need better clothes. They want me to look more mayoral. The fact is, I’m not a professional politician.” As he exits the store, the camera focuses on a black Mercedes. It appears that he’s about to get in the car, but then he puts on a helmet and hops on a moped. “And right now, we have to find a way to get the job done for less money,” he says. The ad was a huge hit and brought him a lot of media attention.

Hickenlooper won in a landslide, and through a savvy approach to budget and other difficult matters became one of the country’s most popular mayors. In this, he was aided by Michael Bennet ’87, who left a lucrative private sector position to become Hickenlooper’s chief of staff, and later superintendent of schools. Bennet, now U.S. Senator from Colorado, brought a seasoned ability to negotiate complex financial deals.

Opposite of Woe does not imply eternal sunshine. Hickenlooper had many difficult moments as mayor, and as governor he has faced severe personal and professional challenges: the dissolution of his marriage, the mass shooting in Aurora, huge wildfires, and a flood of biblical proportions. He engaged in tough battles over bills pertaining to gun control and civil unions, and his advocacy of both cost him politically. Throughout, the “opposite of woe” has meant a refusal to be crushed by reversals and, as he puts it, to maintain a “giddy up” attitude towards life’s travails. A reader can’t help but feel uplifted by this entertaining account of an unconventional life.